The last time I had been down into the East Side Access cavern far beneath Grand Central Terminal feels like eons ago. It was 2015, a time when New Yorkers commuted daily to their midtown offices, and the cavern was very much just that — a large, dark, very unfinished, damp cave that barely resembled a train station.

I took a trip down to the LIRR’s new midtown home two weeks ago, and after six years, I can confidently confirm there is a new Long Island Rail Road terminal deep in the ground below Grand Central. New York has successfully built a train station underneath another train station. The occasion for the trip was celebratory as Gov. Andrew Cuomo and his MTA had just announced that morning, though not for the first time, that the 350,000 square foot terminal will open on time by the end of 2022. It seemed oddly fitting for this long-delayed project that’s taken 20 years and $12 billion to construct that it’s big announcement came amidst a pandemic that has shaken commuting patterns to their very core and has left the future of Midtown Manhattan up in the air, but regardless of the oddities of the times, the Long Island Rail Road will serve the East Side in 18 months or so.

Prior to the press tour of the new terminal, Cuomo hosted one of his famous/infamous pandemic press conference. This was the first one I’ve had the opportunity to sit through, and the Governor spoke a lot, often extemporaneously, making news here and there (particularly about the Gateway Tunnel), and he spoke at length about the challenges of completing East Side Access. “Thanks to the hard work of the so many people, major construction on this transformative project is now complete and we are proud to announce East Side Access will open up next year,” Cuomo said, “significantly cutting travel times and easing the commute into Manhattan for countless travelers. I’ve been through a lot of difficult infrastructure projects during my time in government, and while this project may have been one the most difficult to get accomplished, its completion will have a huge impact on New York’s economy and vibrancy for generations to come and serve as yet another example of what New Yorkers can do when we put our minds to something.”

Cuomo said a lot of eyebrow-raising statements, including claims that the project had stalled out prior to his personal review of it in 2018, and he never mentioned the follow-up L train-inspired review he ordered in April of 2019. He also vowed that the projected 160,000 passengers per day – a relatively paltry total for the billions spent – would be back in their offices by the end of 2022. Maybe he’s right; maybe the world will clamor for the commute and the companionship of the office after 15 months (and counting) of an isolating pandemic. Or maybe the ultimate irony of the East Side Access project will be an opening into a changed world and a changed New York, where we spent countless billions on an under-used deep-bore dead-end terminal underneath Grand Central that never should have been built in the first place. We won’t know this future for a few more years, but this project will never realize full bang for its buck.

Cuomo’s promise to open the station next year come hell or high water set off some familiar alarm bells. When he last made this promise for Phase 1 of the Second Ave. Subway, he opened the subway before systems testing had been complete, and he drove the opening date by diverting massive MTA resources away from subway maintenance. The subway crisis, which lead to the Subway Action Plan and Andy Byford’s Fast Forward plan, grew out of Cuomo’s push to open the Second Ave. Subway, and Cuomo then later tried to take credit for solutions to the crisis he created. Will this drive to open East Side Access — in a similar state of completion — lead to a repeat of recent history? I’m holding my breath. Neither the city nor the MTA can afford that fate at this moment.

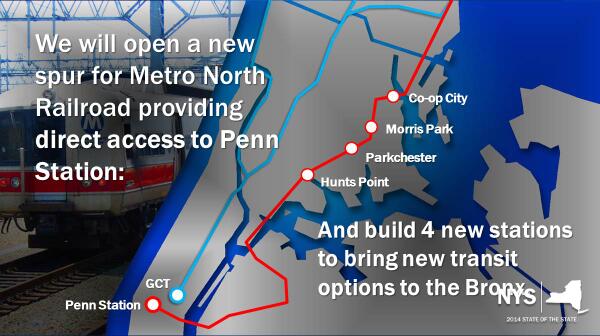

But outside of these concerns and my own long-documented skepticism toward this project and the way the cavern beneath a Metro-North terminal not under capacity highlights the lack of inter-agency cooperation with the MTA, I wanted to offer a few observations about the terminal now that I’ve seen it in its near-finished state. It is, first and foremost, very much an Andrew Cuomo Transit Project. While EXCELSIOR isn’t yet plastered all over the place, the main focus on East Side Access is about getting into and out of New York City, and it does very little to improve getting around NYC. Janno Lieber, the head of MTA Construction & Development, could not answer if the agency planned to further rationalize fares to allow Queens commuters rationally-priced access to LIRR. Cuomo himself spoke at length about how East Side Access will free up space at Penn Station for Penn Station Access, another commuter rail-based project designed to facilitate easier access into and out of NYC (though one with more benefits to Bronx commuters than East Side Access will, on Day One, deliver to Queens).

Thus, the only state-funded project finished under Cuomo’s watch to increase transit capacity in NYC will be Phase 1 of the Second Ave. Subway (and maybe Phase 2 if Cuomo gets another two terms and it moves forward). Meanwhile, the state has spent or will spend billions on Moynihan Station and the Penn Station South/Empire Station complex, the Tappan Zee Bridge replacement, the airport overhauls and new AirTrain and both East Side and Penn Station Access. New York City, with its transit system run by Andrew Cuomo, continues to get the short shrift.

On the physical side, the most evident element of East Side Access is how deep it is. During the press conference, Cuomo tried to sell the depth as a marvel. The new terminal will, he bragged, have 17 high-rise escalators, each 182 feet in length to bring commuters up from 140 feet below Grand Central to the surface. With entrances along Park and Madison Avenues up to around 48th Street, East Side commuters won’t be as far from their offices as they could be, but the depth adds time. The escalators weren’t on during the press tours, but officials said the rides will take 2 minutes at a stand still. These will be the MTA’s deepest escalators, which could spell trouble for an agency with a shaky track record when it comes to escalator maintenance.

The station feels deep in other ways as well. The visual design of the station is very reminiscent of Grand Central itself with similar typefaces and marble used throughout. In an era of OMNY and digital ticketing, there is, for some reason, a massive ticket hall, but I can’t imagine all of the windows ever being staffed. Still, despite bright lights and arching ceilings, the station feels deep. The ceilings are lower than they would be, and there is no sense of place or direction that far underground. When completed the station will feature ample directions, including street signs, to anchor travelers on the Manhattan street grid. Still, it will be bright and clean in the vein of Grand Central when it opens. It’s very deep. Long escalators and low ceilings, despite a generally pleasant, if sterile, aesthetic.

And finally, East Side Access will be another transit mall — which is fine, though it also relies on a return of pre-pandemic commute volumes. The MTA plans to lease out 25 new retail spaces in the terminal, which will give NYC it’s fifth train station/mall and fourth new one this century. Unlike the Grand Central retail spaces, which are a part of the street level attraction, the new retail spaces will be deeper underground and out of the way. Some will be in the passageways at the top of the 182-foot escalators and some will be in the halls connecting to 1 Vanderbilt. But these spaces will be geared far more toward LIRR commuters than the malls in the PATH Oculus, Grand Central itself or Moynihan Station are.

All of this leads me to wonder how East Side Access will work and what it means for it to work? It’s nearly unique among massive train stations and will rely heavily on a return to the old in an era of the new. It’s a project conceptualized in the 1960s, designed in the 1990s and opened, if on time, in 2022.