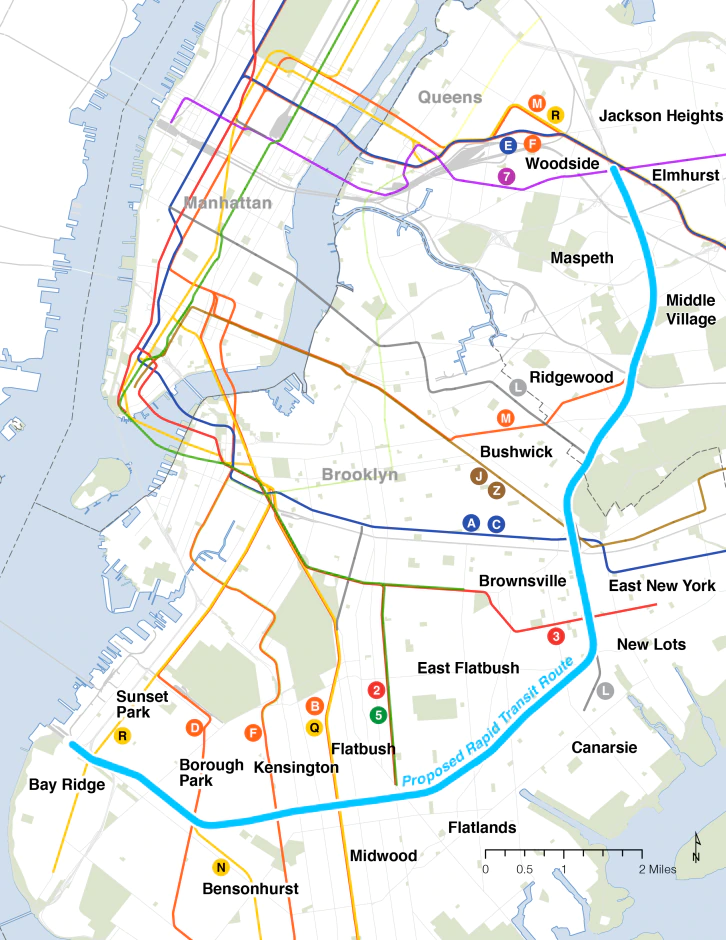

When Gov. Kathy Hochul announced her support last month for a truncated version of the RPA’s 25-year-old Triboro RX proposal, I was surprised. If it survives a gubernatorial election this year, your garden-variety NIMBY opposition and a lengthy review and planning process, the renamed Interborough Express — a 14-mile circumferential route that will connect Bay Ridge to Jackson Heights using an existing freight rail corridor — will become a welcome addition to the city’s transit-scape. But the break-neck pace that started with an out-of-the-blue announcement during her January 5 state-of-the-state speech and continued two weeks later with the release of the MTA’s feasibility study and the start of the environmental review process threw me for a loop.

Why? Because I had simply forgotten the MTA had previously announced plans to study the route. I forgot that they had already cut out the Bronx portion. I forgot it had attracted some support from a handful of New York Assembly representatives. The feasibility study was so out of mind, I didn’t even include it in my transportation to-do list for the new governor last summer. When I looked back at the timing of the MTA’s original announcement, the world could be forgiven for forgetting. The next day, Andy Byford announced his resignation and a few weeks after that, the pandemic descended upon us. The Triboro plan was one of the last bits of normal from 2020, and the feasibility study faded into that Before Times feeling.

But enough about me; let’s talk about the IBX. We’re definitely maybe kinda sorta getting it eventually as Hochul announced last month that the MTA had determined it is indeed physically feasible to add passenger to the freight line. “Infrastructure is all about connection, and with the Interborough Express we can connect people to their family and friends while also improving their quality of life,” the governor said. “The Interborough Express will connect Brooklyn and Queens, not only shaving time off commutes but also making it easier to connect to subway lines across the route. With the completion of the feasibility study, we can move forward to the next phase of this project and bring us one step closer to making the Interborough Express a reality for New Yorkers.”

But what will the Interborough Express be? To learn that, we turn to the Feasibility Study and Alternatives Analysis, a flashy, 28-page PDF that builds on the work the RPA has published on their three-borough proposal, most recently in its Fourth Regional Plan a few years ago. In that document, we learn that the new two-borough plan could be conventional rail, a new light rail or bus rapid transit. At this point, you may be wondering, “Why not Triboro? What happened the Bronx?” Well, as we learned in 2020 and as the MTA briefly notes in the new report, including the Bronx extension would require significant expansion across the Hell Gate Bridge, and due to cost and feasibility concerns, it’s not in the cards for now. Turning the Interborough Express into the Triboro line will be another generation’s problem to solve.

Even without this third borough, the MTA believes that 74,000 to 88,000 passengers per day, depending on the mode, would make use of this circumferential line that begins to fix the Manhattan-centric nature of the subways. It may have made sense in 1922 for nearly all subways to feed into Manhattan south of 60th Street, but in 2022, the need for better connections through the so-called far-flung neighborhoods of the so-called Outer Boroughs could not be more obvious. The 14-mile passenger route would connect with 17 subway lines and the LIRR in Brooklyn and Queens while providing a high-speed, frequent transit service for areas of the city currently heavily reliant on private automobiles for commuting. It makes use of an existing right-of-way, and if the stars align, it’s a project that could be completed by the end of the decade. The MTA hasn’t put a price tag on the alternatives, but MTA CEO and Chair Janno Lieber told reporters the project would be in the “single-digit billions” (which means the Interborough Express can be yours for the low, low price of $9,999,999,999 or less).

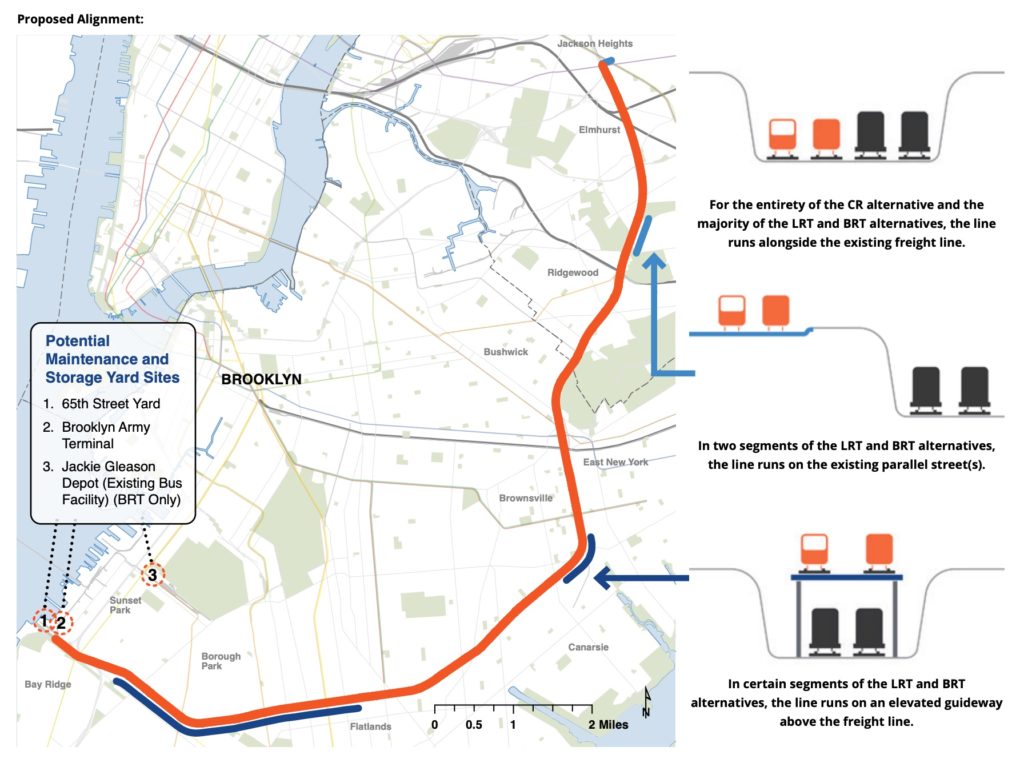

What this not-ten-billion will buy us remains to be seen, but the MTA has narrowed down the options to three: conventional rail sharing tracks with the preexisting freight service, light rail or bus rapid transit. Due to FRA requirements, the light rail and BRT options would have to run on rights-of-way physically separated from the freight service. For most of the route, these two options would exist next to the freight tracks but certain segments would have to run on newly-built viaducts above the Bay Bridge Branch corridor or on city streets.

The conventional rail option is most similar to London’s Overground or Paris’ RER. Trains would look similar to subways, could operate every five minutes and may even interoperate with the LIRR (though the MTA cautions this would be “very complex and expensive”). Ridership is estimated at 84,500 per day, but on the downside, end-to-end travel time for conventional rail is 45 minutes.

From a ridership perspective, the study seems to favor light rail, projecting 39-minute travel time and nearly 88,000 riders. Stations could be built at street level and “smaller LRT vehicles are able to navigate tighter curves and steeper gradients, which in turn reduce the amount of private land that needs to be taken.” But LRT is also the costliest due to the need to build out full physical separation from the freight tracks. The third option — bus rapid transit — would be the “lowest-cost alternative to build” with the “most operational flexibility.” But to meet the projected BRT ridership of 74,000, the MTA would have to run buses every 2.5 minutes during peak hours. The MTA cites “traffic and service reliability impacts” as potential challenges, and I generally favor either of the two fixed-rail options instead.

With the feasibility study completed, and three alternatives tabbed for further review, the MTA at the direction of the governor will move this project into the environmental review phase. Never mind that the agency hasn’t released a 20-year needs assessment since the mid-2010s; never mind that funding remains a mystery. With the governor behind this project serving as its champion, it will move forward. That’s just the way the politics of transit expansion operate.

So next up are some public meetings, and as the line runs through Bay Ridge, Sunset Park, Borough Park, Kensington, Midwood, Flatbush, Flatlands, New Lots, Brownsville, East New York, Bushwick, Ridgewood, Middle Village, Maspeth, Elmhurst and Jackson Heights, those public meetings should be varied. As the study noted, “up to seven out of ten people served will be from communities of color, approximately one-half will come from households with no cars, and approximately one-third will be living in households at or below 150% of the Federal Poverty Line.” While every elected official from these neighborhoods voiced support, Queens Assembly Rep. Cathy Nolan (and some of her more NIMBY-esque constituents) worried about noise though I believe they’re worried about the wrong ROW, focusing their comments on the Montauk Line rather than the route of the IBX.

With key representatives, including council member Bob Holden, on board, political opposition to the IBX is unlikely to materialize from Brooklyn and Queens, but Bronx representatives at clamoring for a piece of the pie. They feel perennial left out of the transit expansion discussion and for good reason. But Hochul wants to move fast, and if we take the MTA at even 40 percent of its word, the connection over the Hell Gate Bridge seriously complicates the project. The beauty of the Interborough Express is that it builds on a pre-existing right of way without the need for complicated construction. At-grade stations are easy; re-arranging the Hell Gate Bridge isn’t. A complicated, lengthy project isn’t in the cards politically, and the Bronx will have to wait.

The biggest wild card may be Hochul’s reelection, but as of now, she’s sailing to her own term and at least four years during which she can use the power of her office to push through this project. In fact, Hochul even managed to get Rep. Jerry Nadler on board. The long-time Congressman had long opposed passenger use for the Bay Ridge Branch as he has spent decades pushing for a freight tunnel under the New York Harbor. As part of the Interborough Express plan, Hochul announced, the Port Authority will examine how the Cross Harbor Rail Freight project will work with the Interborough Express.

“The Interborough Express is an important project that has the potential to expand transit access to underserved neighborhoods in Brooklyn and Queens. This project can and should co-exist with the Cross Harbor Rail Freight Tunnel project which would finally connect the New York metropolitan region to the national freight rail grid by removing trucks from our streets and diverting them to the underutilized rail network,” Nadler said in a statement. “We can and should use the Bay Ridge line to move both people and goods, and I am confident that we can advance both the Cross Harbor Rail Freight Tunnel and the Interborough Express together.”

So where does that leave New York City? This is the most real and concrete step the Triboro/IBX proposal has taken in its decades-long history, and it moves the project from the theoretical pages of the RPA to the real process begun by the MTA. So long as Hochul is the governor and wants to push this through, the project has the transit champion it needs to succeed. At 2 Broadway, there’s even a dream of finishing it by 2030 as the MTA eyes another round of big-ticket transit expansion projects.

I have one final suggestion thought. It could use a catchier name than one that reminds the world of an intestinal ailment. Is the Brooklyn-Queens Express taken? I hear the BQX is an awfully catchy acronym.

For a deep dive into the ins and outs of the challenges that await the Interborough Express and a view of the AECOM report on which the MTA’s alternatives analysis was based, head on over to Streetsblog and read through Dave Colon’s analysis. Alon Levy was disappointed in the narrow scope of the alternatives analysis but finds much to like in the speed at which Hochul is pursuing the project. I agree with Alon on both points.