A set from the next Star Trek movie or an actual rendering of SOM’s plans for Penn Station?

Before I get too far into this little exercise in future planning, let’s remember something about this whole thing: The Municipal Art Society has stressed both to me and to the public that their competition to design a new Penn Station was about transit planning. It was about finding a solution to Penn Station’s train capacity and passenger flow problems while relocating Madison Square Garden and redeveloping the area of Midtown surrounding the train station. It wasn’t supposed to be about undoing the destruction of Penn Station 50 years ago or reclaiming the area for one architect’s ego as has happened with the PATH Hub at the World Trade Center site.

In fact, during a presentation yesterday of the four plans by SHoP, Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, H3 Hardy Collaboration and Diller Scofidio & Renfro, Vin Cipolla, head of the MAS, spoke again about the reality-based nature of the designs. Calling the proposals a “range of practical and liberating possibilities for an expanded, world-class Penn Station and a great new Madison Square Garden,” Cipolla said, “These ideas are buildable. I think everyone took pains to emphasize that.”

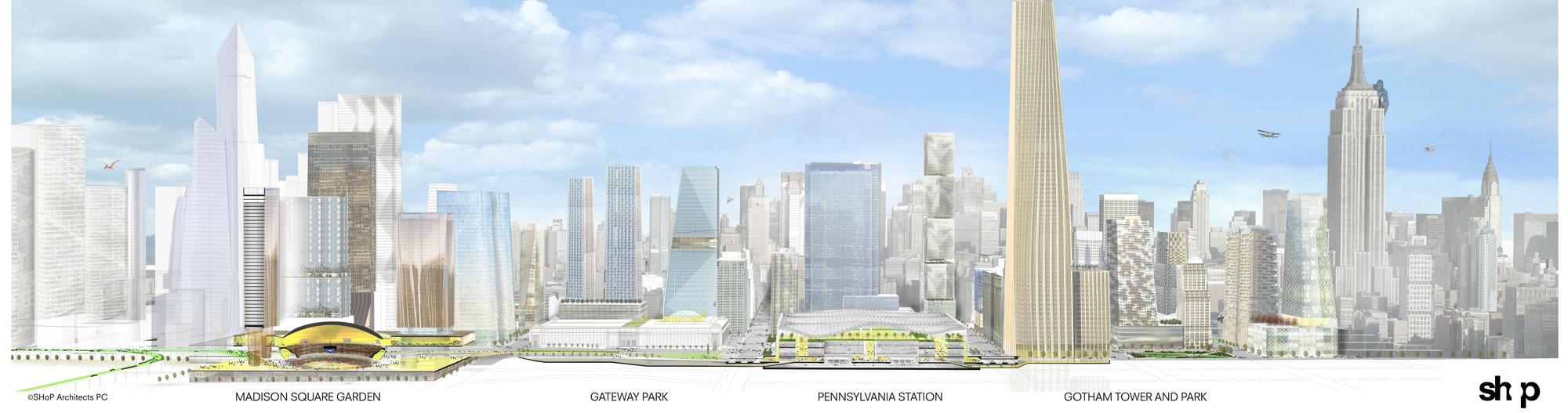

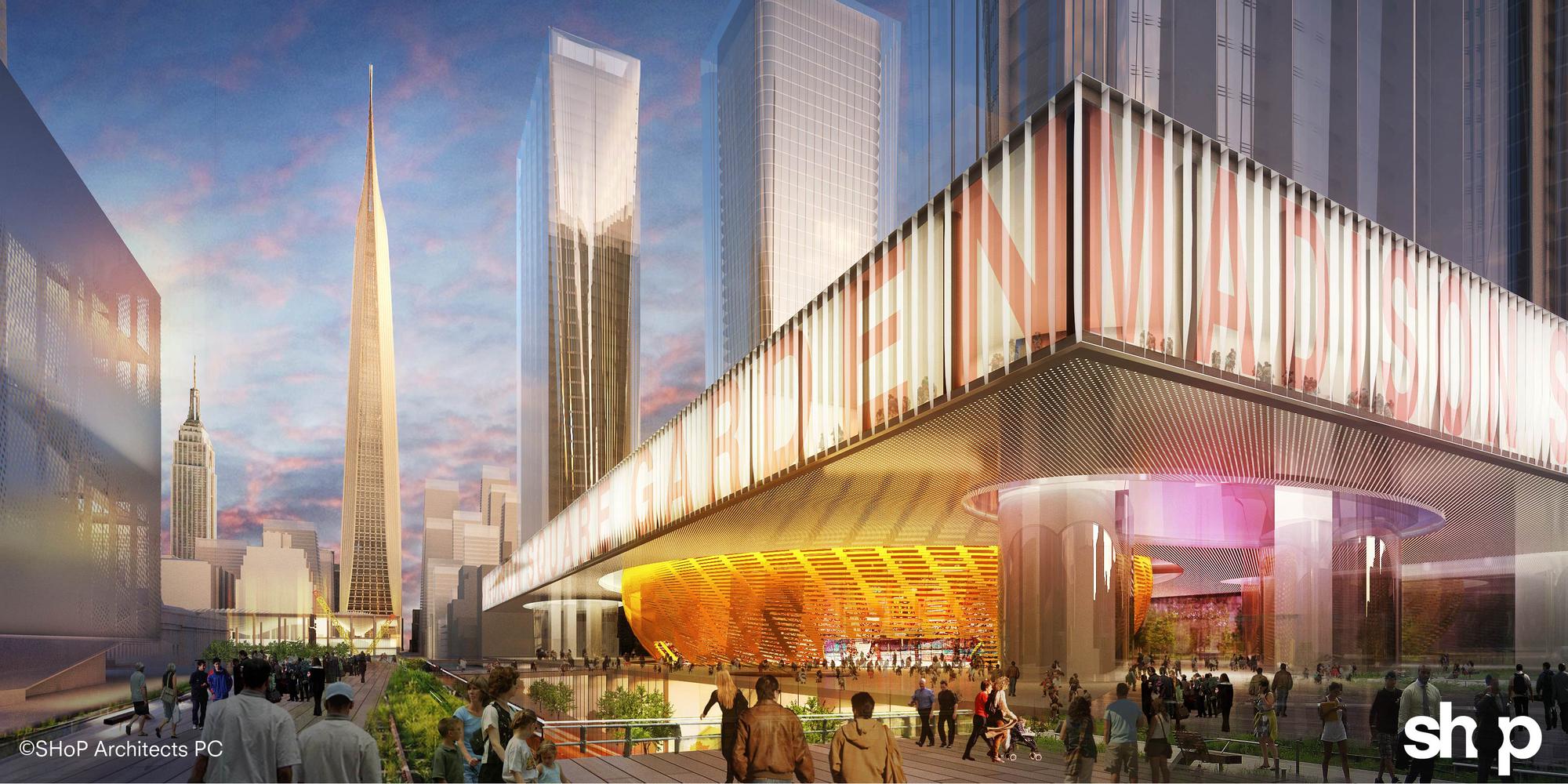

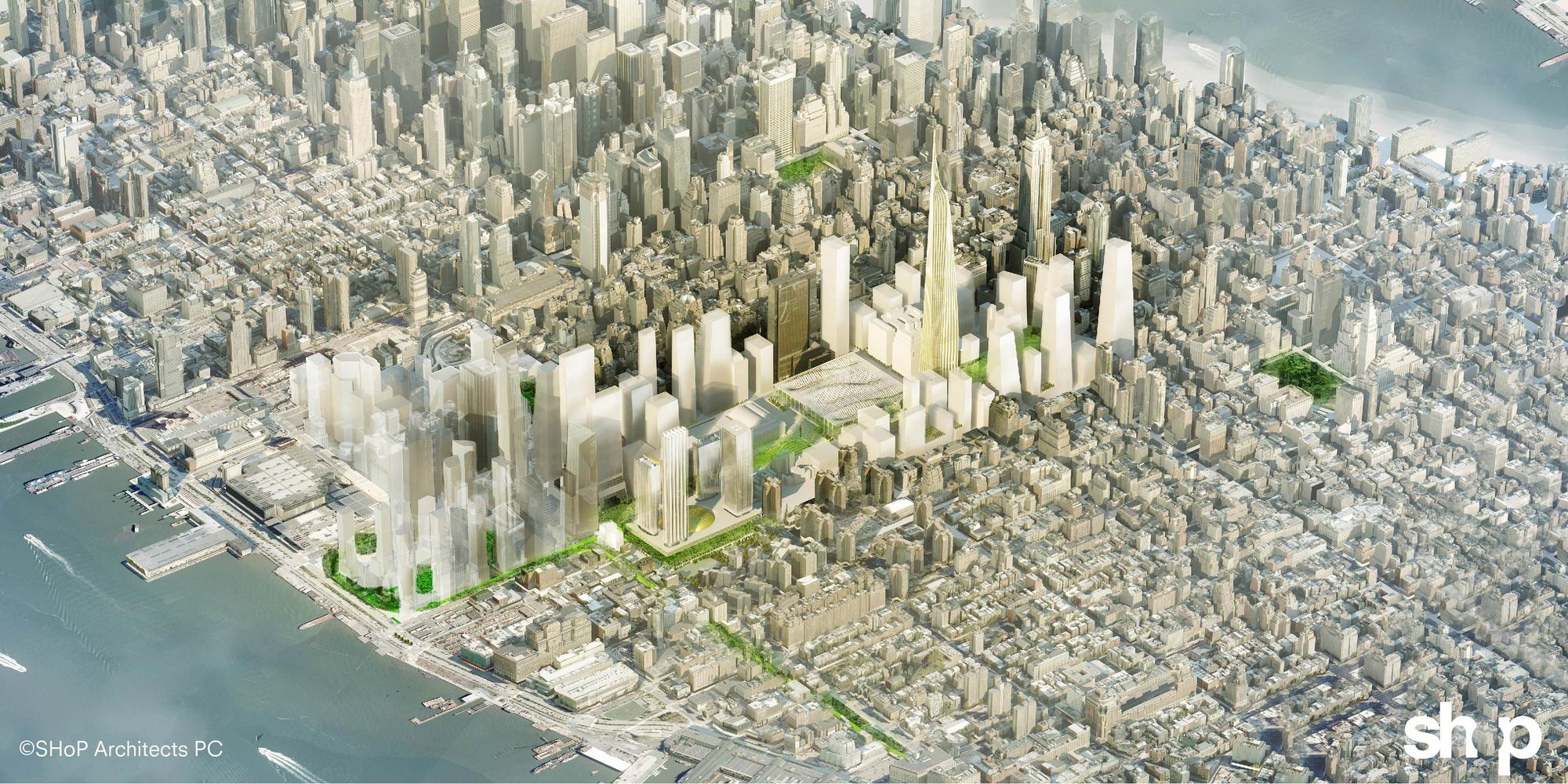

Buildable for Cipolla may not mean buildable for anyone else. One that has drawn the most attention — SHoP’s reimagining of Midtown West from the Hudson Yards and High Line straight on through to the current Madison Square Garden site — came with a price tag. Vishaan Chakrabarti, a SHoP lead, spoke about how their plan would be self-funded through a variety of payments in lieu of taxes and air rights sales. These deals, he claims, would generate the $9.48 billion necessary to realize their design. That’s almost two whole phases of the Second Ave. Subway for the cost of one train station and a new arean. What a bargain.

In a dialogue on Twitter, Chakrabarti later cited to the 7 line extension as a similarly successful project, but that’s a comparison fraught with problems. The 7 line has been under budget because the city cut out half of the proposed train extensions. Furthermore, it has, so far, failed to live up to its economic promises. It likely will recapture a lot of its value, but early returns have not been as high as expected. Attempting to generate $10 billion through a similar program may just be folly.

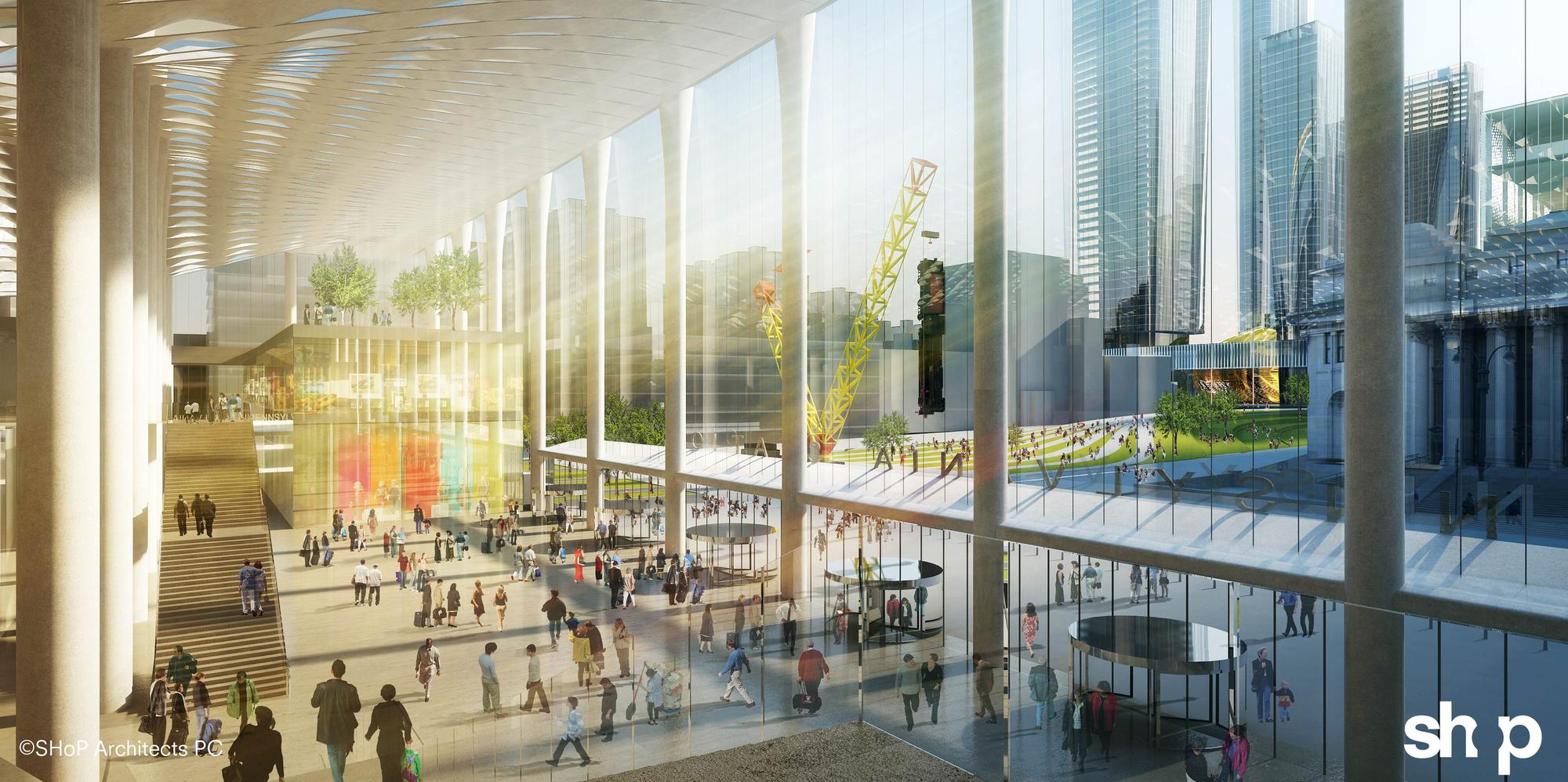

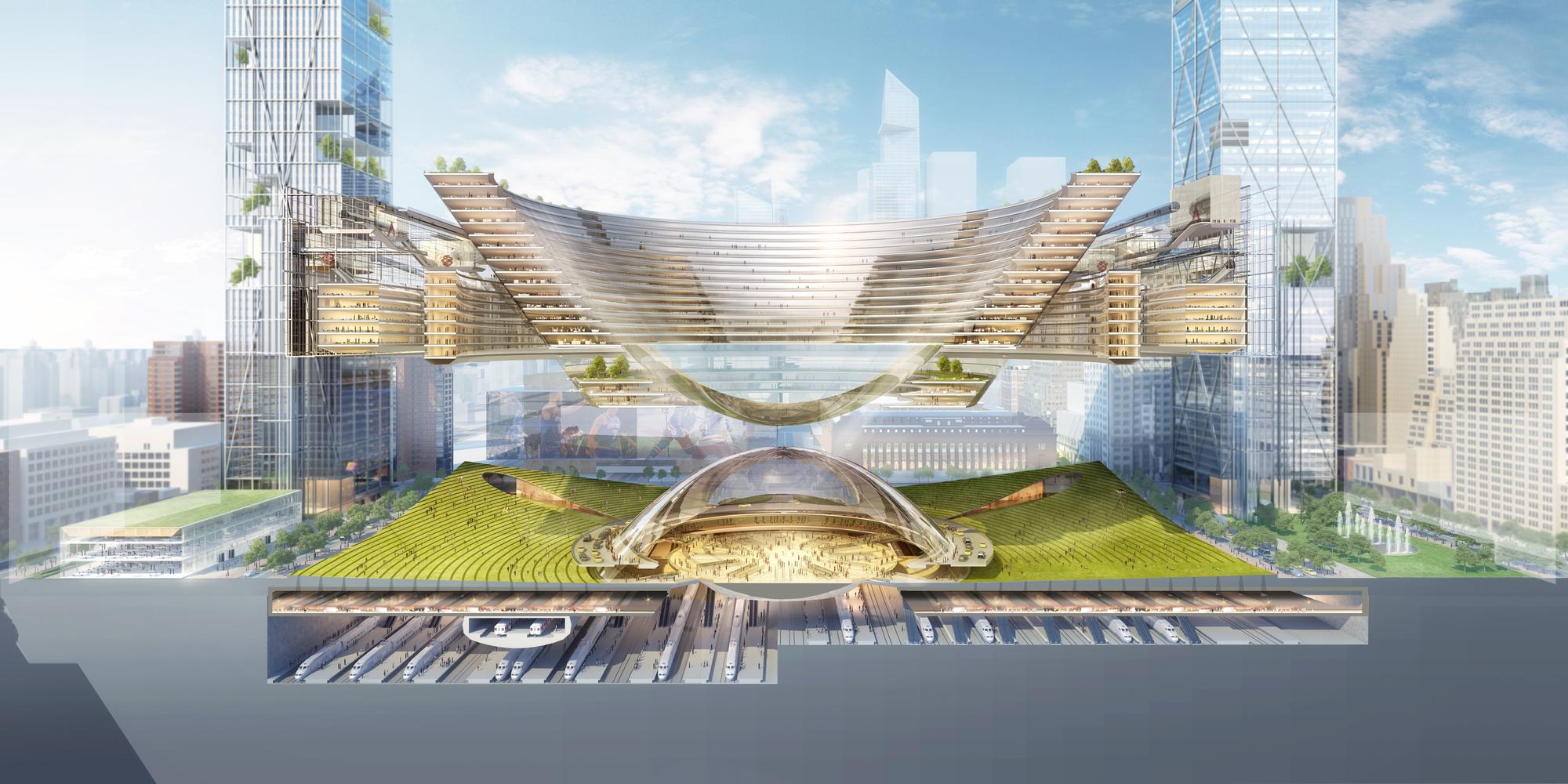

Diller Scofidio & Renfro’s plans move MSG to the Farley building and convert Penn Station into a destination in and of itself.

Even as the renderings capture our attention, the firms seem in it for the wrong reasons. The designs are based on creating a grand building rather than expanding Hudson River rail capacity. “Nearly 640,000 passengers use Penn Station every day, and yet it does not act as a dignified gateway to one of the world’s greatest cities,” Roger Duffy, the design partner who developed SOM’s plans, said in a statement. “What we propose creates a civic heart for Midtown West – one that is truly public and open to all – while allowing New York City to maintain its position as a global center of commerce, industry and culture.”

So what are we left with then? We’re left with fancy renderings that won’t happen, price tags absurdly out of reach, and talking points for Madison Square Garden to dispute this exercise. What we need are some realistic plans for a better Penn Station and reasonable funding goals and mechanisms. As Hilary Baron said to Crain’s, “We have to be careful, given our fiscal constraints, not to get trapped by the old visions of Penn. This can’t be another World Trade Center PATH station.”

Right now, it is both better and worse than PATH. It’s better because no one has committed to fund these things. But it’s worse because it’s a patently silly exercise in imagination with little attention paid to what we can actually accomplish, what we need to accomplish and how, ultimately, we can get there.

Despite my inherent skepticism, it’s still illuminating to look at the renderings and imagine what we could do if money were no obstacle. Click on the thumbnails for much larger versions.

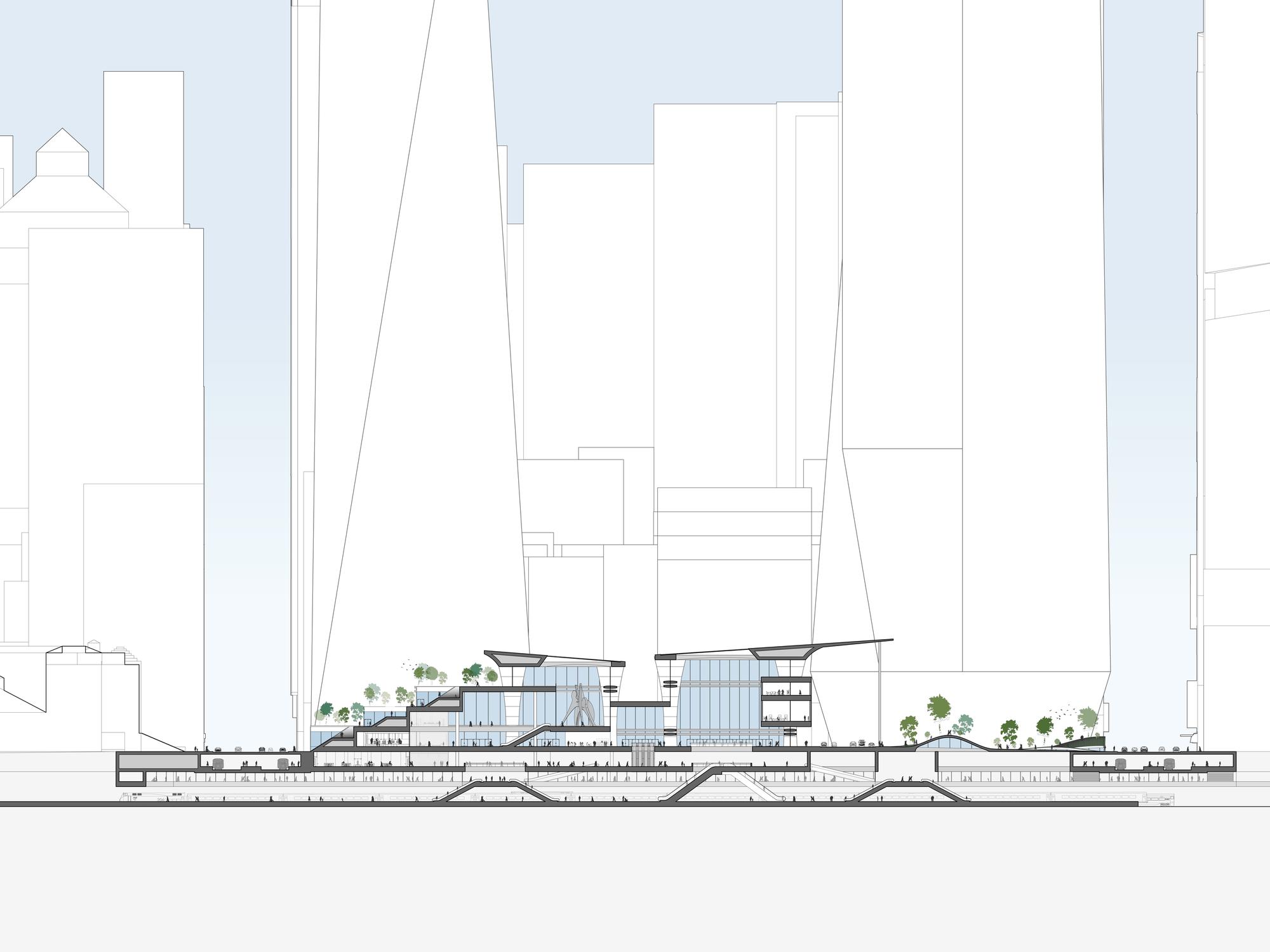

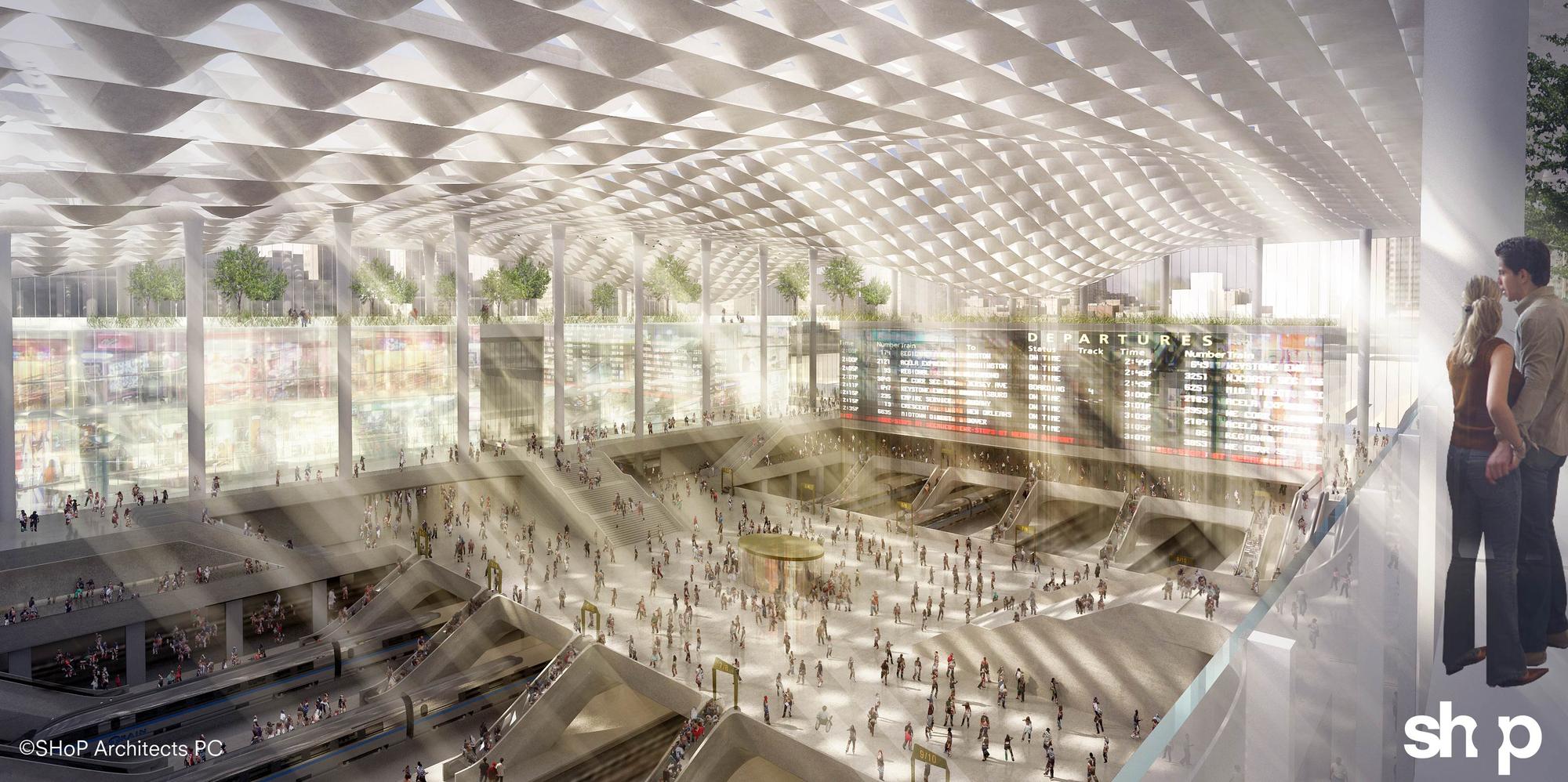

SHoP

SHoP’s grand hall is reminiscent of a modern-day train station but carries a price tag of nearly 11 figures.

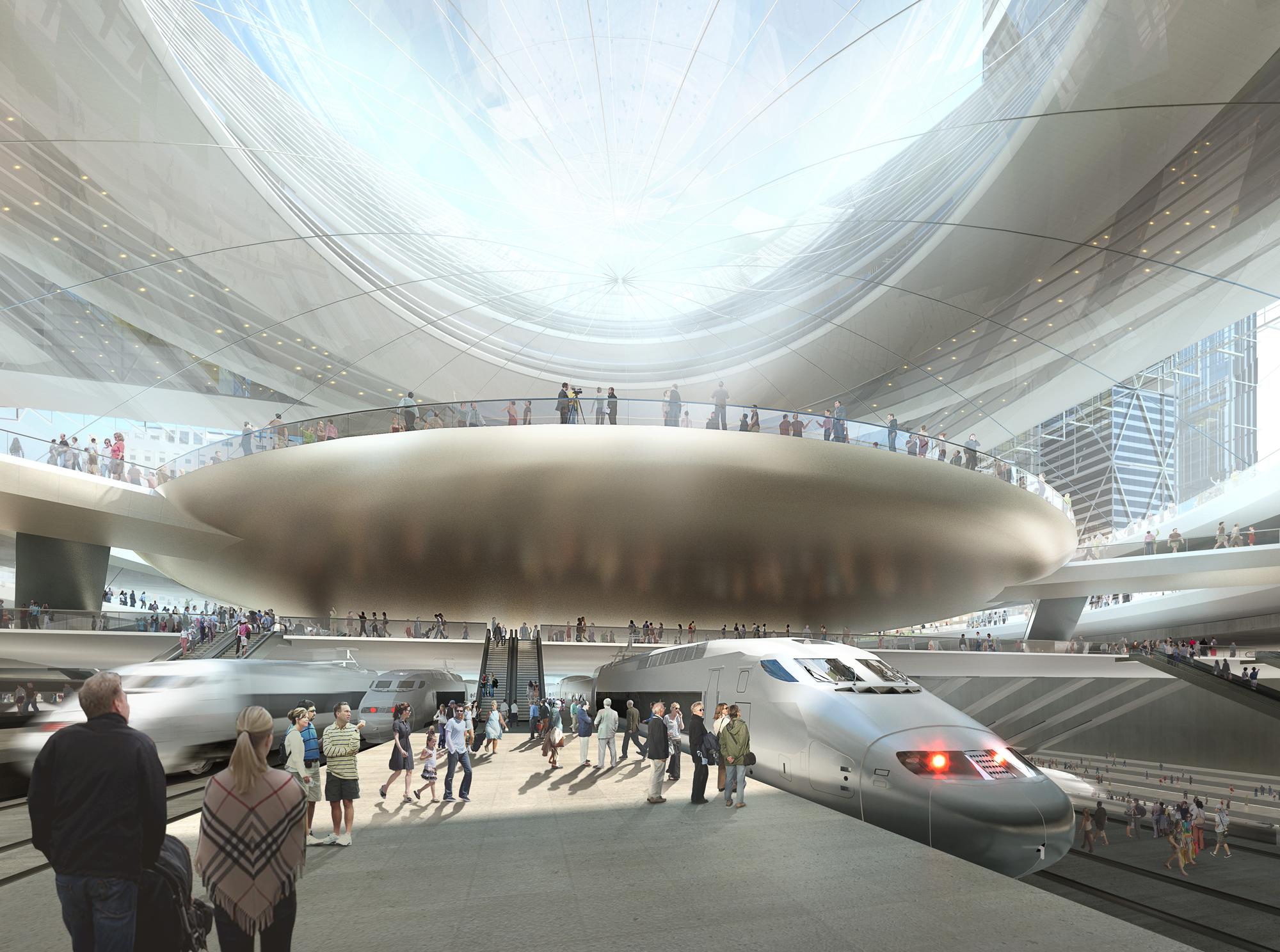

SOM

If you look closely enough, you may see Captain Kirk and some Vulcans boarding an Amtrak train.

H3 Hardy Collaboration Architecture

H3 Hardy Collaboration Architecture