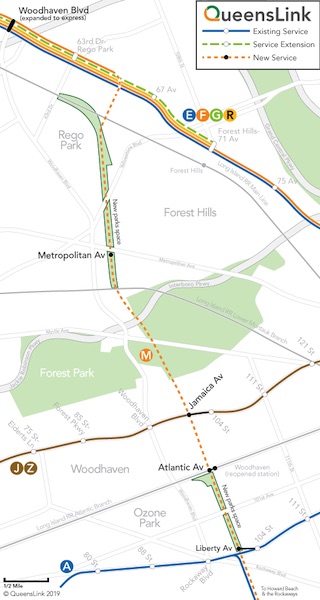

Could the M train one day snake through Queens via the Rockaway Beach Branch line? Some rail activists have a plan that could bridge the rails vs. trails gap if stars, and costs, align. (Via The QueensLink)

Re-activating the defunct Rockaway Beach Branch line could cost up to $8 billion dollars and a one-seat ride to JFK Airport using the once-and-perhaps-future LIRR right of way could run to nearly $20 billion, according to a long-awaited report the MTA released last month. If the MTA’s numbers are to be believed, this report may serve not as a rallying cry for advocates to push for rail reactivation but rather an indication that the MTA’s inability to manage costs will back-burner any transit use for this ROW for years to come. Without an obvious political champion pushing this project, one could be forgiven for believing the inflated costs to be almost intentional.

The history of the Rockaway Beach Branch line is a tortured one that I’ve covered extensively over the years. It’s one of those spaces that’s constantly in the cross-hairs of different groups, and nearly since the day after the misguided decision to end rail service in the early 1960s, various factions have tried to lay claim to the route. We’ve seen dreams of a new Rockaway Beach Branch rail line come and go, plans for one-seat rides to JFK live and die, and over the past decade, fights between the so-called QueensWay group that wants to convert these rails into trails and transit activists fighting for train service into underserved areas. Lately, the folks at The QueensLink have tried to bridge the gap, offering a plan for rail use of the ROW with added park space as well.

Amidst this battle, back in 2016, then-Assembly representative Phil Goldfeder secured state dollars for a study examination reactivation of the RBBL. The report was to be due by mid-2017, but the MTA failed to hit that deadline. Eventually, Systra delivered the report in September of 2018, but it languished out of view until Jose Martinez of The City came knocking in early October. Late last month, the MTA finally unveiled the full report in all its glory.

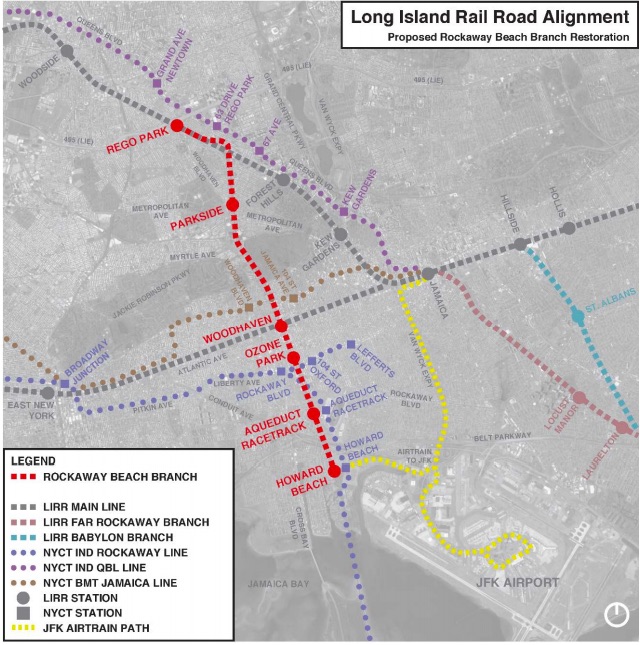

The Long Island Rail Road alignment would return commuter rail trains to the Rockaway Beach Branch.

The report itself is extensive and broken into two phases. The first part [pdf]explores, in great detail, the 3.5 miles of unused right-of-way between Rego Park and Ozone Park where the line then meets up with today’s A train out to Howard Beach and beyond. Systra assessed reactivation via a spur off the LIRR’s Main Line and a New York City Transit spur from the Queens Boulevard line. I’m more intrigued by the subway option that the LIRR routing, but allow me to summarize both.

In each case, the underlying assumption appears to be that most of the current elevated structure — the old Rockaway Beach Branch viaduct — would have to be replaced entirely due to deterioration and modern safety standards, thus driving up costs. The LIRR routing is the cheaper choice but with lower ridership. Sending the Main Line down the Rockaway Beach Branch is projected to cost $6.7 billion and would include new stations at Rego Park, Parkside, Woodhaven, Ozone Park, Aqueduct and Howard Beach. Systra modeled frequencies of 15, 20 and 30 minutes and determined that around 10,800-11,200 riders per day would use the LIRR option with travel times from Howard Beach to Penn Station maxing out at around 25 minutes.

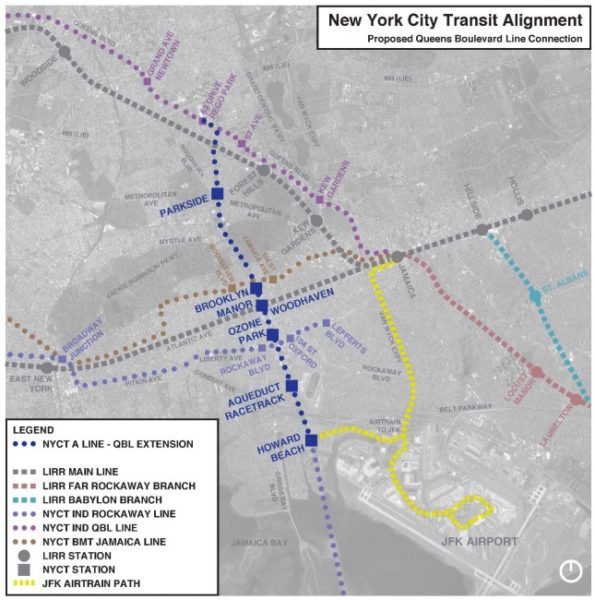

The proposed subway alignment would send a mix of M and R trains to Howard Beach.

The New York City Transit option would include a spur off of the Queens Boulevard Line, approximately 4000 feet of tunneling and new stations at Parkside, Brooklyn Manor, Woodhaven and Ozone Park. As subway junkies know, the current Rego Park station along the Queens Boulevard line has tunnel provisions in place pointed toward the Rockaway Beach Branch right of way, and the report anticipates a mix of M and R trains serving the RBBL with 10-minute headways. Travel times from Howard Beach to Herald Square are estimated at around 45 minutes, and the RBBL could account for 47,000 subway riders per day. This project comes in at a cost of $8.102 billion. Needless to say, both of this plans carry prohibitively expensive price tags, but at least the subway option has a significantly lower cost-per-passenger than the LIRR plan.

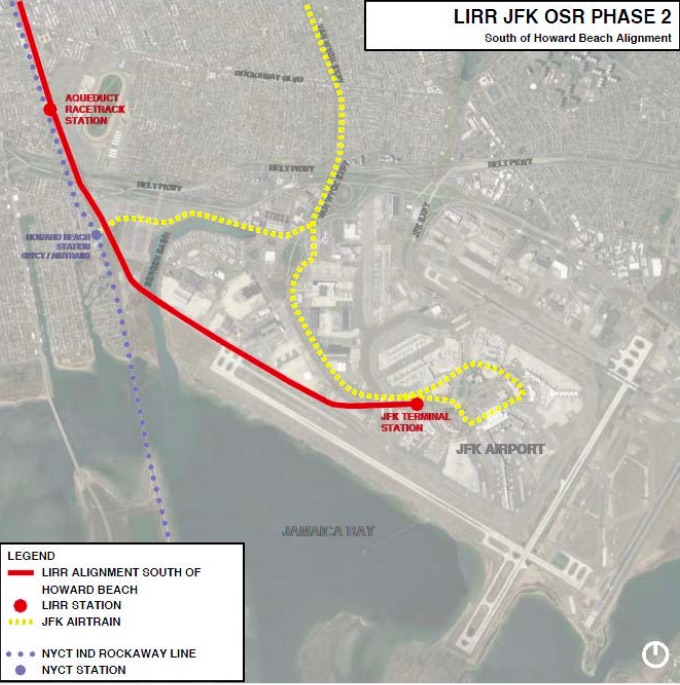

The second part of the study examined using the RBBL to serve as a true one-seat ride from Manhattan right to the terminals at JFK Airport. You can browse this part of the report right here, but I must warn you that the costs make it an exercise in futility. To add on a one-seat JFK extension to the LIRR plan above would cost an additional $12 billion for a total of nearly $20 billion. Travel times range from 23 minutes to and from Manhattan with a stop only at Woodside to 30 minutes to and from Manhattan with local stops in between. Ridership estimates range from around 8000 per day to 15,000, and while the report is an intriguing read with alignment renderings fun to contemplate, the combination of the high price tag and lower ridership make this long-desired one-seat ride an academic exercise in futility rather than a viable plan.

The MTA assessed two options for a one-seat LIRR ride to JFK. The northern alignment (not shown here) would follow the Belt north of Howard Beach before merging with the AirTrain ROW.

Beyond the dollars and the ridership totals, it’s worth paging through the reports, not least to see how the plans are laid out, where stations are sited, and how the modeling anticipates ridership growth. The subway proposal has some challenges. Off the bat, Systra raises concerns that tunneling close to Queens buildings that abut the right of way could damage foundations, and the report calls for proper mitigation. Plus, as we know, certain non-park uses of the right of way will have to be reclaimed. And for what it’s worth, the report allows for joint park and rail usage including via a trail under the viaduct between 97th and Liberty Avenues, parallel to the tracks south of Fleet Street or via an elevated walkway through Forest Park. But none of it is impossible if only the costs were right.

And therein lies the rub. The costs are not right. Each option — the two JFK one-seat alignments north or south of the current Howard Beach A train stop, the LIRR reactivation and the subway extension — are budgeted with excessive cost padding. The subway proposal, for instance, features nearly $2.5 billion in soft costs, $1.2 billion in contingencies, and escalation factors totaling $2.7 billion. The raw construction is estimated to cost only $1.6 billion in 2016 dollars if the tunneling from the Queens Boulevard Line is cut-and-cover. QueensRail advocates who have been pushing the project believe the price tag is unnecessarily inflated and design-build could carve off billions from the soft costs. Still, once the dollars are out there, it’s hard to overcome the political problems these inflated figures create.

Ultimately, then, it’s easy to see this entire report as an exercise in futility and the one the MTA is keen to leave behind. The costs are far in excess of any money the MTA should be spending here, and reaction from all quarters reflects that concern and a healthy skepticism toward the accuracy of the MTA’s cost estimates. In an extensive piece for Crains New York exploring the current state of the rails-vs.-trails debate, Matthew Flamm spoke with former MTA Capital Construction President Michael Horodniceanu. “It’s extremely high,” Horodniceanu said of the cost estimates. “Even though you have a tunnel, the estimate is way out of line.”

Horodniceanu told Flamm he felt construction should come with a price tag “at most” half of what the report predicted, and if the MTA has lost Michael Horodniceanu on cost projections, then they’ve really lost the thread.

I asked Stephen Smith of @MarketUrbanism for his view of the costs as well. Smith, a constant critic of the MTA’s profligate spending, said, “While $8 billion does seem high, even for the MTA in 2019, I think we all should have learned by now to never underestimate the MTA’s ability to spend money. Given the densities along the line, this route is going to be marginal in the best of cases with regards to cost, and we are nowhere near the best of cases, to say nothing of the fact that there’s no evidence that design-build will bring costs down to that. There is so much more lower-hanging fruit in Queens transit, whether it’s bringing the LIRR up to rapid transit standards, running the buses and subway more efficiently, or bringing down construction costs. This project isn’t going anywhere.”

The proposed layout for a Parkside subway station near Metropolitan Ave. may be all we’ll see of the RBBL reactivation plan.

I believe Smith is right. With Goldfeder out of office and his successor Stacey Pheffer Amato losing interest in the project, there is no natural champion even as the need for better rail connections through Queens and into the Rockaways are clearly needed to improve mobility in New York City. To make matters worse, City Council rep Karen Koslowitz, who thinks none of the intermediate stops carefully laid out in the report actually exist, has refused to support rail. “She has always been and will continue to be unalterably opposed to the reactivation of the Rockaway Beach branch,” a spokesman said to Crains New York York. “The neighborhood’s not going to get the benefit of converting it to a public transportation line, but the foundations are going to crack, and homes are going to shake.”

Even if the report details mitigation efforts the MTA could take, at great care and cost, to ensure foundations don’t crack and buildings don’t shake, this is a project without a champion and with a cost far in excess of reason. It’s a lesson in maintaining rail service over rights-of-way and not letting them grow fallow. And it’s a lesson in torpedoing a project an agency doesn’t want to do by inflating the price. New Yorkers will continue to dream and agitate for reactivation of the Rockaway Beach Branch, but until the dollars make sense and political support materializes, the case may sadly be closed.