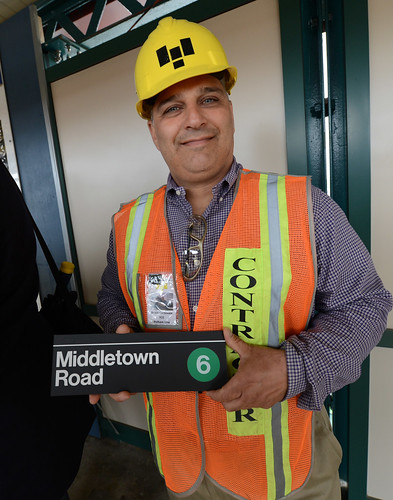

MTA contractors, seen here in a 2014 photo, celebrated the reopening of Middletown Road. The rehab project is now the subject of a federal suit alleging the MTA’s violation of ADA obligations. (Photo: MTA New York City Transit / Marc A. Hermann)

When New York City Transit embarked on the 29-stop station renewal program in 2011 targeting decrepit subway platforms outside of Manhattan, little did anyone realize how momentous this work would become. Last week, more than five years since starting the renovation that spurred a lawsuit — and after many more years of what many advocates have called a clear flouting of ADA requirements — the MTA lost the first round of this ongoing lawsuit as a federal judge ruled that the agency’s component-based repair work at Middletown Road, including replacement of a staircase without the addition of an elevator, was performed in violation of the Americans With Disabilities Act.

The ruling is a sweeping one, as Judge Edgardo Ramos held that the MTA must install elevators when renovating subway stations unless an installation would be “technically infeasible,” rather, as the MTA has argued over the years, too costly, and it is one I and many disabilities advocates saw coming last year when federal prosecutors joined the lawsuit. Even with this ruling on the books, the court battle is far from over as the MTA plans to argue that, in this case, installing an elevator at Middletown Road was indeed technically infeasible, but the decision opens the MTA to significant liability and may require the agency to pursue an aggressive uptick in increasing the number of accessible stations throughout the city.

For its part, the U.S. Attorney’s office took a victory lap. “The MTA is now on notice that whenever it renovates a subway station throughout its system so as to affect the station’s usability, the MTA is obligated to install an elevator, regardless of the cost, unless it is technically infeasible,” Geoffrey S. Berman, the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, said in a statement last week. “Individuals with disabilities have the same rights to use the New York City subway system as every other person. The Court’s decision marks the end of the MTA treating people with disabilities as second-class citizens.”

The MTA, meanwhile, stressed the new philosophy pushed aggressively by Andy Byford: Accessibility is a new top priority. “The MTA is steadfastly committed to improving access throughout the subway, with a hard and fast goal of making 50 additional stations accessible over five years. We’re not wavering from that commitment,” MTA Chief External Affairs Officer Max Young said in a statement.

The question now though is whether that the MTA can perform any substantive work at any subway station without triggering the requirement to include elevators. In fact, I believe the ruling now requires the MTA to build elevators during any rehabilitation work. Let’s dive in.

Nuances in the ADA

The cruz of this case and in fact the long-time basis for the MTA’s antagonism toward installing elevators rests within two paragraphs of federal regulations relating alteration of transportation facilities by public entities. The governing regulation is 49 CFR § 37.43, and paragraphs (1) and (2) of section (a) form the basis for the legal dispute:

(1) When a public entity alters an existing facility or a part of an existing facility used in providing designated public transportation services in a way that affects or could affect the usability of the facility or part of the facility, the entity shall make the alterations (or ensure that the alterations are made) in such a manner, to the maximum extent feasible, that the altered portions of the facility are readily accessible to and usable by individuals with disabilities, including individuals who use wheelchairs, upon the completion of such alterations.

(2) When a public entity undertakes an alteration that affects or could affect the usability of or access to an area of a facility containing a primary function, the entity shall make the alteration in such a manner that, to the maximum extent feasible, the path of travel to the altered area and the bathrooms, telephones, and drinking fountains serving the altered area are readily accessible to and usable by individuals with disabilities, including individuals who use wheelchairs, upon completion of the alterations. Provided, that alterations to the path of travel, drinking fountains, telephones and bathrooms are not required to be made readily accessible to and usable by individuals with disabilities, including individuals who use wheelchairs, if the cost and scope of doing so would be disproportionate.

As you can see, these two paragraphs are very similar and rely on rather arcane legal nuances. Paragraph (1) mandates public entities to make accessibility alterations “to the maximum extent feasible” when altering “an existing facility or a part of an existing facility used in providing” transit “in a way that affects or could affect the usability of the facility.” The only limiting factor is thus the “feasibility” standard.

Paragraph (2) includes a carve-out the MTA has relied upon for years. If a public entity is undertaking an alteration that could affect usability of or access to a transit facility containing a “primary function,” the accessibility alterations may not be required “if the cost and scope of doing so would be disproportionate.” Whenever the MTA has argued that elevators would be too expensive to install, say, for example at Smith/9th Sts., this is the legal provision the agency cites in avoiding the ADA obligation.

What, though, you may be wondering, does it mean to “affect the usability” of a transit facility? And what does it mean for an area to “contain a primary function”? The feds describe a primary function as “a major activity for which the facility is intended” and lists a broad array of examples including fare collection areas and platforms. It seems then that nearly any alteration to a subway station would affect an area containing a primary function, and perhaps, you may think, the MTA has a legal basis for avoiding spending on high-cost elevators. Judge Ramos however does not agree.

The Court’s View

As part of the lawsuit, the MTA had argued that Paragraph (2), rather than Paragraph (1), contained the proper standard. Ramos’ decision essentially asks, “Why not both?” and holds that any time a public entity alters a station in a way that affects the usability in any sense, Paragraph (1), and the obligation to ensure wheelchair access unless technically infeasible, applies. Thus, even if the installation of an elevator would be expensive, the MTA still must include one.

Ramos’ decision rests on his interpretation of “usability.” Relying on previous 2nd Circuit precedence, Ramos determined that alterations that replace something as basic as a staircase with a functionally equivalent staircase do indeed impact the usability of the station:

The Second Circuit found replacements of kitchen floors and bathroom light fixtures to be “alterations” that changed the “usability” of condominium units under Title III provisions analogous to 42 U.S.C. § 12147. See

Roberts, 542 F.3d at 369. Defendants’ replacement of the stairways at Middletown Road Station was clearly an alteration that affected the station’s usability under Roberts. The alteration thus triggered accessibility obligations under § 37.43(a)(1).Defendants argue that § 37.43(a)(2), not (a)(1), applies to the alteration because the renovations were to areas of the station that contained a “primary function.” But (a)(1) and (a)(2) are not mutually exclusive. Under § 37.43(a)(2), accessibility obligations are triggered when “a public entity undertakes an alteration that affects or could affect the usability of or access to an area of a facility containing a primary function.” An alteration can both affect the usability of a facility, which triggers (a)(1), and affect the usability of or access to an area of a facility containing a primary function, which triggers (a)(2). In addition to replacing the stairways, Defendants made extensive alterations to the mezzanine and platform floors of the station. Since these floors are where tickets are bought and trains are boarded, they clearly contain primary functions. Therefore, the Court agrees with Defendants that § 37.43(a)(2) also arguably applies to the renovations made at Middletown Road Station.

The MTA’s request for the court to determine that Paragraph (1) did not apply to Middletown Road was rejected, and at this point, by nature of this lawsuit, the MTA cannot argue elevators are too expensive. Rather, the agency must rely on the argument that doing so is “technically infeasible.” The court will hear arguments on just that very question regarding Middletown Road in the coming months.

What Does This All Mean

Now, all of these regulations and legal analysis may make your eyes gloss over, but it’s important. For all practical purposes, based on this ruling, whenever the MTA does anything substantive to a subway station, the Paragraph (1) obligations to install elevators will apply. Thus, any of the stations that were recently renovated via the ESI program are likely in violation of the ADA, and any other component-based stations that were renovated without full accessibility are likely in violation of the ADA as well unless the MTA can prove elevator installation would be technically infeasible and not just cost-prohibitive.

As you can imagine, this will cause some consternation for station rehabs going forward. While the MTA has pledged to meet an obligation to make 100 Key Stations fully accessible by the end of 2020, any minor work to spruce up stations could be thrown in doubt. I believe the MTA could craft an appeal as the analogy Ramos made between renovations of a condo — which sees a true increase in value due to new floors and bathroom lighting — is a weak one and the crux of the legal decision. After all, the idea that a like-for-like replacement of a staircase affects or otherwise alters the usability of a subway station seems to be a stretch.

But the feds have long been clear that any post-1991 renovation to old structures grandfathered into the ADA were supposed to include full accessibility work, and even with a basis for appeal, the MTA will face an uphill battle to overturn this case. Whether the court will require the MTA to install elevators at all stations they’ve renovated in recent years remains an open question.

Meanwhile, since the component-based station rehab project kicked off, the MTA has significantly changed its thinking on accessibility. Andy Byford has expressed public displeasure that only 24 percent of stations are accessible and has promised 50 additional accessible stations within the next five years as part of his unfunded Fast Forward plan. That’s a laudable goal and one that may be accelerated as any work of substance the MTA performs on subway stations will now trigger ADA obligations.

Still, as always, without cost control, this lawsuit could carry a steep price tag for an agency that can’t figure out how to install elevators for a reasonable price. If it takes the full weight of the judiciary to force the MTA to cut costs, so be it. We’ll all be better off for it as accessible stations improves transit access for anyone who has to carry bags, push strollers, deal with injuries or grow too old to climb stairs. It’s high time for the MTA to work toward fully accessible stations throughout the city, judicial opinion or otherwise.

“This ruling highlights why the New York City subway system remains overwhelmingly inaccessible to people who cannot use stairs,” Michelle Caiola, Managing Director at Disability Rights Advocates and one of the parties to the case, said. “If MTA had been complying with the ADA over the past twenty-five years by installing elevators when it performs station renovations, we would be closer to full accessibility today. Clearly, MTA must change its practices related to accessibility as soon as possible.”

Once upon a time, before the 2010 cuts decimated transit service in NYC, the MTA worked to ensure that off-peak subway service met increasing demands. From 2000 until 2010, as off-peak demand, especially between 5 a.m.-7 a.m., increased, the MTA responded in turn, adding more service so that the percentage of off-peak trains generally aligned with the percentage of riders using the system during these early hours. But since 2010, as New York City’s economy has rebounded from the depths of the recession and off-peak commuting has increased, the MTA hasn’t added service at a commensurate level, and this service gap is hurting New York’s lower-income workers, according to

Once upon a time, before the 2010 cuts decimated transit service in NYC, the MTA worked to ensure that off-peak subway service met increasing demands. From 2000 until 2010, as off-peak demand, especially between 5 a.m.-7 a.m., increased, the MTA responded in turn, adding more service so that the percentage of off-peak trains generally aligned with the percentage of riders using the system during these early hours. But since 2010, as New York City’s economy has rebounded from the depths of the recession and off-peak commuting has increased, the MTA hasn’t added service at a commensurate level, and this service gap is hurting New York’s lower-income workers, according to