Via Infrastructurist and Martha Kang McGill comes this snapshot of urban life in America. McGill took census data to illustrate how people in various cities across the country commute to work, and while Houston’s red is reflected in tales of traffic jams and pollution, New York’s blue is a soothing reminder of our need for a vibrant subway system. No other city in the country approaches New York City’s reliance on public transit just as a means of commuting to work, and the state and city should remember that as they prepare to let the MTA’s coffers run dry. (Click the image to enlarge. It’ll open in a new window.)

View from Underground

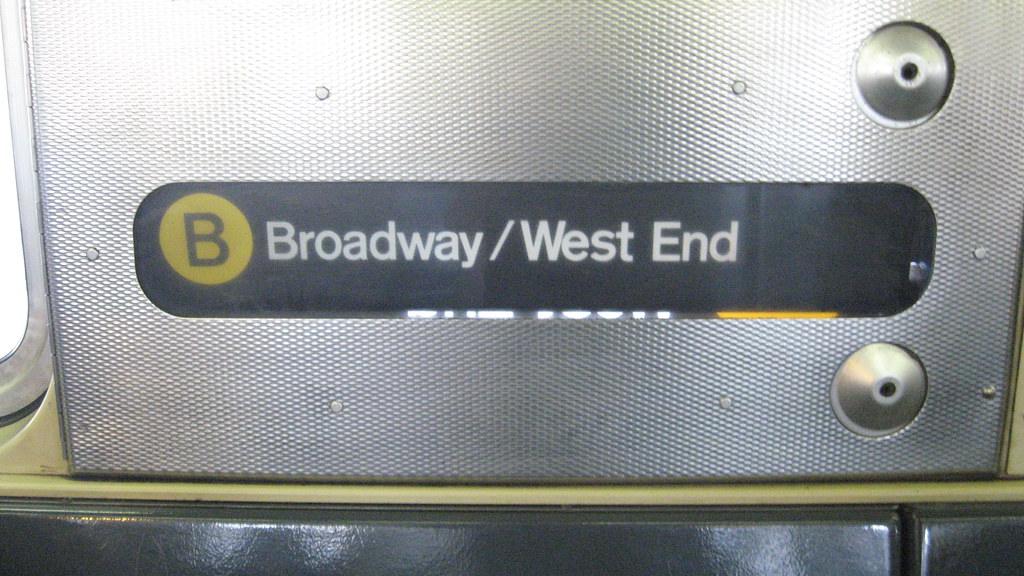

The many colors and destinations of the B train

A rollsign from years gone by recently on display on the B train. (Photo by Benjamin Kabak)

I took the picture atop this post on Dec. 8, 2009. It was shortly after 2:15 when one of the last remaining R32s to make the B run pulled into Broadway/Lafayette, and the car I boarded was just flat-out wrong. As is evident from the picture, the B, normally running down the Sixth Ave. line and then the Brighton line out to Brighton Beach, was confused. It seemed to think it was running the BMT Broadway/West End Line, and while most passengers hesitated to board the train, most seemed content to ignore this anomalous rollsign.

For the B train, errant rollsigns are not an occurrence all that rare. Due to the Manhattan Bridge construction that spanned three decades and lasted nearly twenty years, the B train has been rerouted more frequently than any train, and for significant chunks of the 1990s, two different B trains — one orange and one yellow — ran various routes in Manhattan and Brooklyn. In fact, a few months before boarding the confused B, I saw another slightly less lost B train:

So why the divergent history? The tale lies in the MTA’s need to adequately serve Brooklyn and in the need to shore up support for the Manhattan Bridge. Because the subways lines are on the outside lanes of the bridge, the joints on the bridge were severely stressed for decades, and by the mid-1980s, trains could only crawl across the bridge for fear of structural damage. Facing a disaster, the city and MTA finally began work on a decades-long project to steady the bridge. It would prove quite disruptive to subway travel and did not wrap until 2004.

To accomplish its task, the MTA had to close various sides of the bridge for long stretches of time. Today, the B and D trains run along the northern tracks on the bridge to Grand St. and up the Sixth Ave. IND line. The Q and N take the southern crossing and enter Manhattan at Canal St. before heading north along the BMT Broadway line. But that is a creation of the last six years. How then did service used to look and why are these rollsigns as they are?

Well, when the northern tracks were closed, the B train ran in two segments. One trip took riders from 168th St. in Manhattan — now a C train stop — to 34th St./Herald Square along the IND routes under Central Park West and Sixth Ave. That was the orange-and-white section. The other part of the trip started at either 21st St./Queensbridge in Queens or 57th St. and Broadway in Manhattan and carried the B over the southern Manhattan Bridge tracks. The train would travel along the West End line and terminate in Coney Island as the D does today.

When the southern tracks were closed, the B would invariable run via the 6th Ave. line, across the bridge and to Coney Island. At times, the B was truncated and saved as a Brooklyn shuttle between Atlantic Ave./Pacific St. and Coney Island. Sometimes, it would run weekedays-only, and sometimes, just in Manhattan. The fact that the B has had a stable route for the last six years and counting is a modern creation.

When the Bridge reopened for good in 2004, Transit had to address changing conditions underground and changing travel patterns. In 1986, when the Bridge closed, people were generally not too keen on riding the subway, and no one wanted to go to Union Square or Times Square, major destinations of the BMT Broadway line. So when faced with the chance to run trains that could spur to either route, the MTA polled riders and found a preference for the Broadway route that hadn’t existed 18 years earlier. As The Times detailed then, the routes were adjusted and for a few weeks, confused reigned.

Today, we know the B as the Brighton Express. It’s an orange-and-white bulleted train that runs only during weekdays and not at all during the overnights. It’s a speedy ride into Manhattan, and it’s the train I take more than any other these days. Today, it’s a very stable ride, but now and then, when someone sets an improper rollsign, the B can still remind of construction from years past.

Unlawful arrest for subway photography costs city $30K

Taking pictures in the subway isn’t illegal, but good luck convincing NYPD’s transit officers of that fact. In what has become a series of similar cases, the City of New York had to pay out $30,000 to a man who was unlawfully detained for snapping some subway shots.

Fox 5’s John Deutzman reports that Robert Palmer was at the Freeman Station in the Bronx last year when cops ordered him to stop shooting photos of the subway. When Palmer respectfully declined to erase his pictures and showed the cops his copy of the subway rules that say, “Photography, filming or video recording in any facility or conveyance is permitted,” he was handcuffed.

The cops then booked Palmer for not one but three violations. He was charged with, according to Fox, “taking photos,” “disobeying lawful order/impeding traffic,” and “unreasonable noise.” Palmer says he wasn’t being confrontational or rude, and the three charges were eventually dropped. The NYPD admitted that Palmer shouldn’t have been charged, and Palmer sued the city for his unlawful detainment. The actions of police ignorant on the law cost taxpayers that $30,000.

To make matters worse, as Fox 5 news crews were filming this story, Deutzman had his own run in with a transit authority worker. He reports, “Some guy who claimed to be a transit supervisor actually put his hand over the camera’s lens to try to stop the Fox 5 camera guy from recording video. When the so-called supervisor figured out the crew was with Fox 5, he backed off saying he didn’t realize we were ‘working press.’

As the report notes, the NYPD has sent a memo to its service members reminding them that photography is legal. Transit has done the same. Yet, still the cops and employees haven’t gotten the message. How many more taxpayer dollars will it cost the city before the rules become the rules?

Having a station renovation cake and eating it too

In a few years, the stations along the Culver Viaduct will be fully renovated.

The Culver Viaduct — a pesky strip of the IND Culver Line that crosses the Gowanus Canal 90 feet above ground — is in very bad shape. The bridge is structurally unsound, and the stations are decrepit with paint peeling from leaky ceilings and windows boarded up. By 2013, the Culver Viaduct will be fully renovated, and with the completion of that project will come renovated stations and the potential for F express service. In the meantime, service changes and weekend cancellations make for uncertain travel via the F and G trains.

For this mile-long strip of above-ground track, the work is badly needed. Waterproofing has given way to waterlogged and stressed concrete, and this overhaul is the first major rehab since 1933 when the viaduct first opened. It is an old structure and surrounded by buildings, and the MTA knew it would not be an easy overhaul. Yet, many have embraced it. Residents in the area have long recognized how dangerous the viaduct had become and were happy to see the MTA begin work on it.

Happy, that is, until service changes came to rule the weekends. As The Post explained yesterday, the work on the viaduct will result in total weekend shutdowns with shuttle bus service in between Jay St. and Church Ave. for weekends in February, May and November. Brooklyn residents are not happy about this development. “People are going to totally freak out,” Laura Stryjewski said. “Taking the shuttle is a royal pain. This is terrible news.”

Others were even more critical. “They already put us through this six months ago,” Isabel Milenski said to The Post. “It’s like they’re not fixing the issue. The shuttle rides are grotesque. It’s going to be chaotic.”

Milenski’s comment and Stryjewski’s to a lesser extent are both patently absurd. Of course the MTA is fixing the issue; that is, after all, why the Viaduct, a 77-year-old structure, has to be closed for a few weekends during the course of construction. To claim otherwise is simply ignorant.

These comments, featured in a major daily newspaper, are designed to stir up some sort of populist outrage at the MTA. Look at those transit folks, canceling our service and making us take shuttle buses, suggests the tone of the article. I’ve harped on this point before, but it’s worth repeating: This is simply irresponsible journalism. Who cares with some man- or woman-on-the-street thinks about something about which they are largely ignorant? If The Post wants to make the MTA look bad, this hit-and-run journalism is exactly the way to do it. If the paper cared about informing its riders of the MTA’s efforts at restoring this stretch of its track, it could do so in a more newsworthy way.

In the end, though, these attitudes transcend the yellow journalism of The Post and get at a deeper problem with the way people treat transit in New York City. The people who complain about how dirty, dingy and unsafe the Viaduct is are the same folks who complain about shuttle buses and station closures when the MTA gets around to fixing things. These riders want everything, and they want it now. Simply put, they can’t have it. The Viaduct has to be closed because the MTA needs to do major structural repairs to it otherwise the station will remain a part of the city’s crumbling transportation infrastructure. Ever the demanding bunch, New Yorkers cannot have it both ways for once.

For more on the Culver Viaduct project, check out my old posts here, here and here. After the jump, a video from the MTA about the rehabilitation work.

A video primer on the emergency brake

Who would have thought that the emergency brake — a fixture of subway cars for decades — could generate such attention? Over the last few weeks, I’ve burned quite a few pixels opining on the problems with the way Transit labels its emergency break. The dialogue started late last month when we explored how, in case of emergency, riders aren’t supposed to pull the brake and continued with a look at how the emergency instructions don’t say when to pull the brake.

In a nutshell, Transit urges its riders to avoid pulling the brake if the police or fire crews are needed. “Do not pull the emergency break,” reads the emergency brake decal. Rather, the emergency brake should be deployed only if a moving subway car has placed someone’s life in danger. That seems to be a rather straightforward instruction that is nowhere to be found in the city’s subway cars. And so in the grand spirit of the internet, a few intrepid filmmakers put forth a homemade PSA about the brake. The five-minute video — available here on Vimeo and embedded below — is quite amusing.

Meanwhile, in his new Off The Rails column at City Room, Michael Grynbaum spoke to the makers of this video who drew their inspiration from a Grynbaum article. Casey Nesitat is a 28-year-old filmmaker who hates riding the subway and spent around $25 on the film. It ends with instructions from the MTA’s website: “Use the emergency brake cord only when the motion of the subway presents an imminent danger to life and limb.” If only the signs in the subway cars were that concise.

Scenes from New York’s subway past

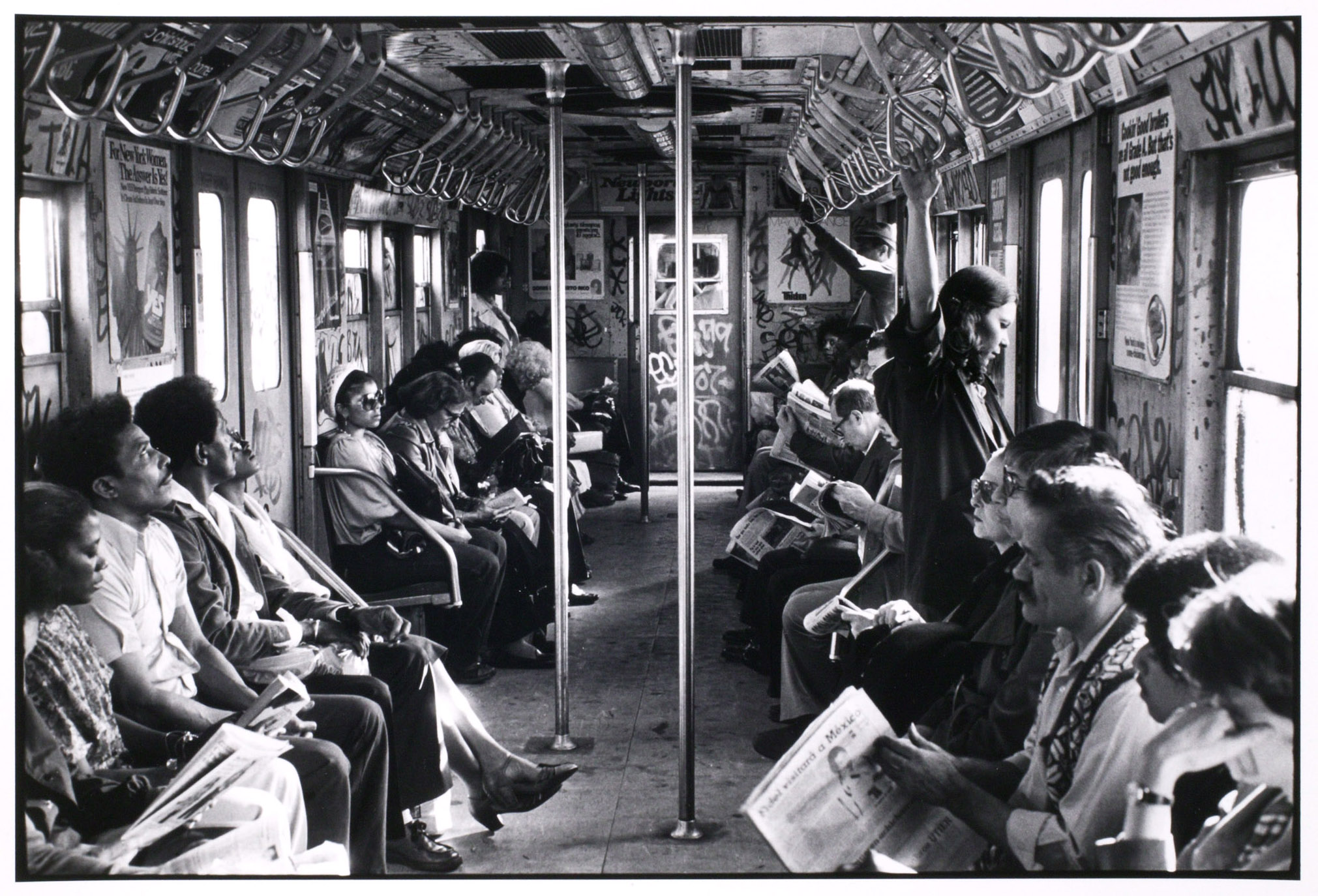

Danny Lyon, IRT 2, South Bronx, New York City, 1979. (Courtesy of Fans in a Flashbulb)

A few years ago, when the NYPD and the MTA briefly concerned banning photography in the subway system, New Yorkers were, as a quick Google search shows, up in arms about the move. Shooting photos in the subway has become an iconic part of New York life and culture, and by mid-2005, the two agencies had dropped the camera ban.

Today, over at Fans in a Flashbulb, the International Center of Photography offers up a tantalizing glimpse at some subway photos from New York’s past. They highlight just five photos, and the shots, ranging from a 1943 Weegee shot of a crowded subway station serving as an air shelter to a 1995 Steven Siegel photo of the Culver Viaduct looking as rundown as it does today, leave you wanting more.

My favorite is the 1979 glimpse inside a graffiti-covered 2 train in the South Bronx. The subways were once so dingy, and everyone was so complacent about the state of affairs underground. In a way, that attitude exists today as New Yorkers still don’t view the subway system as something in which we should be investing instead of as an inconvenient means of transportation. Anyway, as these shots show, great photography underground can truly capture the essence and flow of the subways. Enjoy ’em.

MetroCard sales: How we pay

Earlier today, the MTA Board held its first meeting of 2010, and prior to that meeting, the agency released its board materials. As I’ve done in the past, today, I’d like to take a look at some of the myriad transit statistics offered up in these presentations. Let’s delve today into the Transit Committee book (PDF). In particular, I’d like to explore how the subway riding public purchases its MetroCards.

First, as the above table shows, we can explore how those who ride the subway pay for their trips. This chart shows the number of non-student passenger trips, and it appears as though the Unlimited Ride/Pay-Per-Ride gap is evenly split. According to Transit, 50.7 percent of riders used an Unlimited Ride card with the bulk of those employing the 30-day unlimited ride card. Those are the frequent commuters. Of the remainders, 45.3 percent resorted to the pay-per-ride card with the majority of those taking advantage of the MTA’s bonus discount program. Four percent — bus riders — paid via cash.

What we see here, then, are smart commuters. Over 86 percent of all subway riders are taking advantage of the MTA’s discount fare offerings and are what I would consider to be daily or near-daily riders. The remaining 14 percent are most likely tourists and visitors to the city who do not understand the pay-per-ride discount or find themselves rarely using trains. Of course, some tourists will buy unlimited ride cards as well. Interestingly, the 14-day MetroCard isn’t seeing much traction, but I wonder if those numbers increase in December when vacation times increase.

Beyond the pure fare card numbers here, Transit presented various other facts about MetroCard use. For example, those who purchase their 30- and 14-day passes from a MetroCard Vending Machine with a credit card can take advantage of the MTA’s automatic loss insurance. Transit reports 5387 lost MetroCard claims in November 2009 for an average refund amount of $51.09. Apparently, straphangers lose and report their MetroCards well before the midway point of the month.

The agency then runs through a variety of numbers. Employer-based providers of pre-tax transportation benefits purchased 209,110 MetroCards valued at $13.9 million in November, and the mobile sales unit generated just over $97,000 in sales. Meanwhile, the EasyPay Xpress Unlimited program — an auto-bill program that charges a user’s credit the $89 for a 30-day card once a month — isn’t generating much use. While 2794 customers are enrolled in this program, they rode just 120,831 times in November. That 50-trip average drops the price-per-ride of the 30-day card to $1.78, not much lower than the pay-per-ride discount.

Finally, we have monthly totals as well. The MTA’s own MetroCard Vending Machines saw 13.3 million customer transactions in November for a total revenue intake of $171.1 million. Of note is this fact: “Debit/credit card purchases account for 66 percent of total vending machine revenue while cash purchases account for 34 percent. Debit/credit card transactions account for 36 percent of total vending machine transactions while cash transactions account for 64 percent.” The average cash sale, says Transit, is $6.87 while the average credit and debit card purchases are $26.10 and $19.71, respectively.

And that is how we rode in November and how we paid for our rides.

Bob Noorda, transit sign designer, dies at 82

Underground, Massimo Vignelli is the superstar of the design of subway signs. He is largely credited with bringing a uniform design to the subway system shortly after the formation of the MTA in the late 1960s. Vignelli, who at the time was with the design firm Unimark International, did not work alone. He brought Bob Noorda, a leader in Modernist design with him, and Noorda was one of the driving forces behind Transit’s eventual use of its now-ubiquitious and familiar signs.

Underground, Massimo Vignelli is the superstar of the design of subway signs. He is largely credited with bringing a uniform design to the subway system shortly after the formation of the MTA in the late 1960s. Vignelli, who at the time was with the design firm Unimark International, did not work alone. He brought Bob Noorda, a leader in Modernist design with him, and Noorda was one of the driving forces behind Transit’s eventual use of its now-ubiquitious and familiar signs.

A few weeks, Mr. Noorda passed away in Milan at the age of 82. His cause of death, one of his associates said, was complications from head trauma suffered after he fell recently. Over the weekend, Steven Heller of The Times penned an obituary that highlighted Mr. Noorda’s work in New York City.

As Heller tells the tale, Noorda, then based in Unimark’s Milan office, came to New York at the request of Vignelli in 1966 when the MTA commissioned the firm to help unify their signs. “I remember when Bob came to New York and spent every day underground in the subway to record the traffic flow in order to determine the points of decision where the signs should be placed,” Vignelli said.

Continues Heller:

The existing signs they encountered were cluttered with various typefaces of different sizes. “Their system was a mess,” Mr. Noorda was quoted as saying in “Unimark International: The Design of Business and the Business of Design” (Lars Müller), a recently published book by Jan Conradi. “Sometimes pieces of paper taped to the wall were the only indication for the station.”

He and Mr. Vignelli set about standardizing the type family to make sure that the signs were cleaner and clearer; they settled on Helvetica, originally a Swiss design known for its sans serif economy and sterility, against a white background. Mr. Noorda worked on every detail, from typeface selection to color coding. He “had a very systematic mind,” Mr. Vignelli said, adding that “his work was extremely civilized.”

Yet the project proved disappointing to the designers. The M.T.A. was responsible for executing the designs and producing the signs in its own sign shop, and Mr. Noorda’s directives were not always followed. The sign makers, for example, at first chose to use Standard Medium, a typeface from their own shop. “They did not want to invest in Helvetica,” Ms. Conradi wrote.

In the end, Noorda and Vignelli’s black-on-white designs were replaced by the MTA with white-on-black signage. The agency always maintained that the white-on-black designs were easy to clean and did not get as dirty as Noorda’s original creation. Although Noorda’s may have been easier to read in a dimly lit subway stop, the MTA’s edits proved more durable, and today, the Akzidenz Grotesk font on a black background, often with a thin white line running through the top, symbolizes the city’s subway system.

For many, the MTA’s signs have always just been there, but they are both a product of hard work and a remnant of Modernism that lives on in New York. It will be decades before someone comes along to overhaul New York’s subway signage, and today, as we remember Bob Noorda, his work lives on.

Sign illustrations courtesy of Noorda Design and the MTA. A hat tip on this sad news goes to my mom who sent me the obituary over the weekend.

The conductors that you meet each day

Over at his Ink Lake blog, Friend of Second Ave. Sagas Peter Kaufman has up a post on the various styles of subway conductor. Riffing a famous picture of Clint Eastwood, Lee Van Cleef and Eli Wallach, Kaufman highlights the three personalities of those in charge of getting passengers onto and off the trains while keeping to a demanding schedule. The Good is one who “opens the doors promptly at the station, and doesn’t shilly-shally when closing. If someone on the platform hesitates, their decision is made for them. The doors are closed, and the train is on its way.” The Bad are those who are overly considerate. These are the ones who allow passengers to just catch the train, but as Peter writes, the delays can add up to make trips 15 percent longer than scheduled. The Ugly are those who “try closing the doors even as people are still exiting the train, let alone anyone boarding.”

I’ve seen them all, and in a way, Kaufman’s simplified view of conductors really nails it. Of course, sometimes the Bad are held hostage by riders holding the doors, and sometimes the Ugly are just trying a bit too hard to keep their trains running on time. A good conductor will have his or her timing down just right, and for those people running to make the train, well, there’s always “another one directly behind us.”

Behind the Voices: Transit announcements

As new rolling stock replaces the old cars, the era of the conductor in the subway system is coming to an end. Automated pre-recorded announcements that are easier to hear are replacing individual conductors’ efforts at announcing the next stops. Some people bemoan the loss of individuality underground while others prefer the crisper and over-enunciated sounds of the new announcements. Either way, those disembodied voices have become ubiquitous underground, and earlier this week, the voice recognition blogged Whose Voice is That? explored the personalities behind the voices. Did you know that the female voices usually provide information while the male voice provides instructions and commands? Since 2000 Charlie Pellett, Jessica Ettinger Gottesman, Dianne Thompson and Catherine Cowdery have been ordering us around underground, and WViT has the goods on them.