I’m too tired of political bickering over the MTA’s capital plan to tackle the subject this late on a Monday night. So I’ll be back on Tuesday with more substance. In the meantime, ruminate on Pizza Rat, a symbol of New York City and its subway system. This rodent is all of us, trying to grab a bite to eat and utterly failing at it, but he tried. A real New Yorker would have folded that slice before taking it down to the L train at 1st Ave.

As United investigation continues, what future the Newark PATH extension?

Will a federal investigation or a $2 billion price tag sink the Newark PATH extension?

New Jersey Governor Chris Christie is continuing his push for the White House as trouble circles a few of his pet projects back at home. As an outgrowth of the investigation into the George Washington Bridge lane closure scandal, United Airlines’ CEO and two of the airlines’ top executives resigned, and the feds haven’t closed the books on potential criminal charges. In the background — or perhaps the foreground of this mess — is the Port Authority and the planned PATH extension to the Newark Airport train stop.

We first heard of the latest iteration to send the PATH from Newark Penn Station to the airport two years ago when news broke of a $1 billion plan Christie had been considering. Eventually, the costs grew to $1.5 billion, and as I explained in my last post on the project ten months ago, it was overpriced, underutilized and inefficient. The costs, as you’ll see, may now be around $2 billion, and a multi-billion-dollar extension to a transfer point to an AirTrain already served by rail with a projected daily ridership of 6000 is simply a terrible use of the finite dollars available for transit expansion.

Meanwhile, underlying the initial proposal was a sense that something else rather than rational transit planning was driving this project forward. Ted Mann first wrote about the horse-trading with United back in September of 2013. Reportedly, Christie’s team had asked for United to serve Atlantic City in exchange for state support and funding for the PATH extension. It was politics at its finest.

Now, certain Garden State factions want to put a hold on the PATH extension, and it’s creating tension in Trenton. Earlier this month, state lawmakers urged the Port Authority to put the project on hold at least until the feds are through with their investigation. “The Port Authority should suspend any further spending on that project until United Airlines’ internal investigation, the findings, become public, until the criminal investigation of that becomes public,” NJ State Senator Paul Sarlo said.

Port Authority officials defended the project. “The extension of PATH to Newark airport was a proposed capital project long before David Samson was chairman of the Port Authority,” Christie appointee and current PA Chair John Degnan said. He cited a Regional Plan Association endorsement as proof that “the project stands on its own.”

Still, considering the issues with this proposal, it’s not a surprise state officials want the Port Authority to prioritize a new bus terminal and a trans-Hudson tunnel before the agency revisits this flawed PATH extension. Meanwhile, though, Newark politicians want to keep moving on the PATH extension. John Sharpe James, a Newark councilmen, spoke out forcefully in favor of the plan:

James, however, said the project had been extensively studied by regional planning groups and the Newark Housing Authority, and was not being pushed through haphazardly. “This expansion is not an overnight decision,” he said. “It’s sorely needed and its probably one of the most massive projects in this area.”

…James, who represents the city’s South Ward, said residents of the Frelinghuysen and Dayton Street area, where the extension and a new train station would be built, are counting on it to bring jobs and new fortunes to an area that has long been rife with crime and abject poverty…Following news of the Port Authority’s commitment to the extension, multiple hotels have begun plans for construction in the areas outside Weequahic Park, which officials have hoped might spur further development in one of the city’s most economically depressed neighborhoods.

James said he was concerned that those calling for a halt to work on the PATH line might have reservations beyond any potential malfeasance by United. During last week’s hearing, Weinberg said the nearly $2 billion the project might require might be better used on a new Port Authority Bus Terminal or the proposed Gateway trans-Hudson rail tunnel. “I believe the folks who have been talking have their other pet projects they want to fund,” James said.

There’s very little doubt that “pet projects” like a trans-Hudson rail tunnel would be far better for the region than a PATH extension that won’t stop between Newark and the airport. But that’s besides the point. The latest version of the PATH proposal may have come about through illegal backroom dealings, and even if it didn’t, at $2 billion, this is a laughably terrible idea. With this price tag, we’re through the looking glass on lack of bang for the buck, and the Port Authority should not proceed with this project. If it takes a major investigation into malfeasance between the state of New Jersey and United to get to that point since politicians won’t or can’t look at it rationally, so be it. I’m sure this isn’t the end of the line for this story though.

Straphangers’ best and worst; a 1 train shutdown; weekend work

Earlier this week, the Straphangers Campaign handed out their annual subway rankings, and they mysteriously awarded the 7 line the top spot while knocking the B and 5 train to the bottom. It’s confounding to see this rankings because they don’t make much sense. The C and R trains all perform much worse than the B and 5, and the F and G suffer on seat availability and service consistency. The B I take every day, and it’s an average subway line for what it is (which is complementary service along routes with other express or local trains), and the 7 is a packed train suffering from unreliable service due to an array of issues. But that’s all anecdotal anyway.

Earlier this week, the Straphangers Campaign handed out their annual subway rankings, and they mysteriously awarded the 7 line the top spot while knocking the B and 5 train to the bottom. It’s confounding to see this rankings because they don’t make much sense. The C and R trains all perform much worse than the B and 5, and the F and G suffer on seat availability and service consistency. The B I take every day, and it’s an average subway line for what it is (which is complementary service along routes with other express or local trains), and the 7 is a packed train suffering from unreliable service due to an array of issues. But that’s all anecdotal anyway.

I’ve had bones to pick with the Straphangers’ methodology in the past, and the awards are designed to garner headlines more than anything else. That a major riders’ advocacy group claims most subway rides aren’t worth the fare is problematic by itself. If you’d like to read their full report, have at it.

Anyway, as Friday night rolls into Saturday, the weekend service advisories are focused around the 1 train, or lack thereof. The MTA has shut down the 1 train for the entire weekend. Alternate service includes the 2, 3, A and C trains, some regular Manhattan buses and free shuttle buses. It’s not ideal for anyone, and the MTA put out a press release calling the work “absolutely critical in order to provide safe, reliable service into the future.” The work includes brick arch repairs at 168 St and 181 St, repairs in the vicinity of 125 St, track panel installation north of 215 St and ongoing Hurricane Sandy recovery work at the South Ferry station. The 2 and 3 will still run local.

Here’s everything, straight for the pens of the MTA:

From 11:30 p.m. Friday, September 18 to 5:00 a.m. Monday, September 21, 1 trains are suspended in both directions between Van Cortlandt Park-242 St and South Ferry. Take the 2/3/A/C trains, M3, M100 and free shuttle buses instead. 3 service operates between Chambers St and 148 St overnight.

From 11:30 p.m. Friday, September 18 to 5:00 a.m. Monday, September 21, 2 trains run local in both directions between Chambers St and 96 St.

From 11:30 p.m. Friday, September 18 to 5:00 a.m. Monday, September 21, 3 trains run local in both directions between Chambers St and 96 St.

From 11:45 p.m. Friday, September 18 to 7:30 a.m. Sunday, September 20, and from 11:45 p.m. Sunday, September 20 to 5:00 a.m. Monday, September 21, Crown Hts-Utica Av bound 4 trains run express from 125 St to Grand Central-42 St.

From 11:45 p.m. Friday, September 18, to 5:00 a.m. Monday, September 21, 5 trains are suspended in both directions between Eastchester-Dyre Av and E 180 St. Free shuttle buses operate all weekend between Eastchester-Dyre Av and E 180 St, stopping at Baychester Av, Gun Hill Rd, Pelham Pkwy, and Morris Park. Transfer between trains and shuttle buses at E 180 St.

From 11:45 p.m. Friday, September 18 to 5:00 a.m. Monday, September 21, Brooklyn Bridge-City Hall bound 6 trains run express from 125 St to Grand Central-42 St.

From 3:45 a.m. Saturday, September 19 to 10:00 p.m. Sunday, September 20, Brooklyn Bridge-City Hall bound 6 trains run express from Pelham Bay Park to Hunts Point Av.

From 7:30 a.m. to 9:00 p.m. Saturday, September 19 and from 11:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. Sunday, September 20, 6 trains run every 16 minutes between 3 Av-138 St and Pelham Bay Park. The last stop for some trains headed toward Pelham Bay Park is 3 Av-138 St. To continue your trip, transfer at 3 Av-138 St to a Pelham Bay Park-bound 6.

From 12:01 a.m. Saturday, September 19 to 5:00 a.m. Monday, September 21, A trains are suspended in both directions between Euclid Av and Ozone Park-Lefferts Blvd. A service operates in two sections between Inwood-207 St and Euclid Av, and between Rockaway Blvd and Far Rockaway every 20 minutes. Free shuttle buses operate between Euclid Av and Lefferts Blvd, stopping at Grant Av, 80 St, 88 St, Rockaway Blvd, 104 St, and 111 St. Transfer between trains and free shuttle buses at Euclid Av and/or Rockaway Blvd.

From 3:45 a.m. Saturday, September 19 to 10:00 p.m. Sunday, September 20, Coney Island-Stillwell Av bound D trains are rerouted via the N line from 36 St to Coney Island-Stillwell Av.

From 6:00 a.m. to 11:30 p.m. Saturday, September 19 and Sunday, September 20, World Trade Center-bound E trains skip Briarwood and 75 Av.

From 11:45 p.m. Friday, September 18, to 5:00 a.m. Monday, September 21, Jamaica-179 St bound F trains run express from Neptune Av to Smith-9 Sts.

From 11:45 p.m. Friday, September 18, to 5:00 a.m. Monday, September 21, Jamaica-179 St bound F trains run express from W 4 St to 34 St-Herald Sq.

From 6:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Saturday, September, 19 and Sunday, September 20, Coney Island-Stillwell Av bound N trains are rerouted via the R line from Canal St to Atlantic Av-Barclays Ctr. Trains stop at City Hall, Cortlandt St, Rector St, Whitehall St, Court St, Jay St-MetroTech, and DeKalb Av.

From 11:45 p.m. Friday, September 18 to 5:00 a.m. Monday, September 21, Astoria-bound N trains are rerouted via the D line from Coney Island-Stillwell Av to 36 St.

From 11:45 p.m. Friday, September 18 to 10:00 p.m. Sunday, September 20, Coney Island-Stillwell Av bound Q trains run express from Prospect Park to Kings Hwy.

From 6:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Saturday, September, 19 and Sunday, September 20, Coney Island-Stillwell Av bound Q trains are rerouted via the R line from Canal St to Dekalb Av.

From 6:30 a.m. to 12 midnight Saturday, September 19 and Sunday, September 20, R service is extended to the Jamaica-179 St F station.

From 11:45 p.m. Friday, September 18 to 6:30 a.m. Sunday, September 20, and from 11:45 p.m. Sunday, September 19 to 5:00 a.m. Monday, 36 St-bound R trains stop at 53 St and 45 St.

Doctoroff: Actually, now let’s build that 41st St. 7 train station

A 7 train station at 41st St. and 10th Ave. is likely nothing more than a dream today.

As Mayor Bill de Blasio and a pair of surrogates for Gov. Andrew Cuomo engaged in political sniping over the MTA’s capital plan during Sunday’s opening of the 7 line extension, a few feet away and well out of the fray sat former NYC Deputy Mayor Dan Doctoroff. The one-time Bloomberg side man could bask in the belated success. After all, the 7 line extension was one of his pet projects, originally attached to Doctoroff’s doomed 2012 Olympics bid, and while Michael Bloomberg served as the public face of the city’s funding commitment, Doctoroff did all the dirty work behind, and sometimes in front of, the curtain.

Some of Doctoroff’s more notable performances came in mid-2007 when it became clear that the station at 41st St. and 10th Ave. would not survive the budgetary axe. As I explored a few weeks ago, losing that second stop represents a big missed opportunity for New York City, and that is, in no small part, thanks to Doctoroff.

In late 2007, when the city could have afforded the $500 million extra it would have cost to build the second station, Doctoroff disingenously offered a 50-50 split with, well, anyone. The MTA had held firm on the idea that they weren’t going to spend significant dollars on the 7 line extension, and the feds had prioritized the 2nd Ave. Subway over the 7 line, a move Doctoroff would not easily forget. When Bloomberg’s administration offered to go in on half the cost overruns, these officials knew no one would take them up on this offer, and the station died a painful death.

Now, Doctoroff has had his “come to Jesus” moment. As he and James Meola, another long-time Bloomberg ally and appointee, wrote in this Sunday’s Daily News, they now feel it’s time to fund and build this station. There is nothing quite like closing the barn door eight years after the horse escaped. Wrote the pair:

The challenge, then, was to find the money to pay for the subway extension and related amenities. The city developed a novel plan: It would issue bonds but ask bondholders to accept repayment only out of incremental tax and other revenues generated from the district over and above the amount the city collected in the year before the project began. While the city agreed to pay the amount of any difference between new tax revenue and the $153 million in annual interest payments, that was the extent of its obligation. The bondholders accepted the risk that there wouldn’t be enough development and tax revenues to pay them back. In a way, it was the ultimate expression of faith in the future of New York.

A casualty of the financing plan was a second subway station at 42nd St. and 10th Ave. Without a track record, we just couldn’t raise the money to pay for the cost of the second station and the parks that would serve the northern section of the District…

Based on our calculations, if we just take into account the buildings that have been completed, are in construction now, or are in the advanced stages of planning, over the next 30 years Hudson Yards will throw off $30 billion on that investment of $353 million! Now that it is clear that the financing structure has become so successful, the city should expand it by borrowing an additional $1 billion and using the proceeds to pay for the 10th Ave. station, which could be completed in about five years, and the additional parks. The total cost is but a small fraction of the profits that the city already is expected to generate from the original Hudson Yards financing structure.

Doctoroff, of course, has nothing to lose here, and he can even restructure history. The city knew Hudson Yards would be an economic development success story and could have foot the bill, through a variety of financial means, years ago. Instead of a station for $500 million built contemporaneously with the rest of the project, Doctoroff now proposes a station built for over $800 million that would likely be severely disruptive to the 7 train operations.

That’s not even the most interesting part of Doctoroff’s about face. A few years after calling the 2nd Ave. Subway, a “silly little spur that doesn’t generate anything,” Doctoroff now claims to see the benefit of “provid[ing] subway service to the currently underserved areas around it, including northern Hudson Yards and parts of Hell’s Kitchen.” The station, he argues, would also help alleviate congestion at Times Square — hardly the same grounds he used to build the 7 line to Hudson Yards and certainly not new arguments put forward by those who have long wanted that second stop.

Ultimately, Doctoroff’s change of heart is a big nothing. We can wallow in his hypocrisy or we can view it as progress. But either way, no one — not de Blasio, not Cuomo, not the MTA — is rushing to fund a station at 41st and 10th, and despite a lackluster call yesterday from The Times editorial board to build the station, most people I’ve spoken with both in and outside of the MTA don’t believe we’ll ever see this station become a reality. The time to build it was eight years ago. That ship sailed, thanks to Doctoroff and his boss, and no amount of Daily News columns can right that wrong.

Cuomo, Christie offer the feds a 50-50 split on a trans-Hudson rail tunnel (but it may not be Gateway)

Will New Jersey and New York fund Amtrak’s Gateway Tunnel or something else similar but of its own creation? (Map via Amtrak)

While Gov. Andrew Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio are fighting over everything transit these days as part of their Albany-City Hall feud, Cuomo has found a transit ally across the river in an unlikely source. On Tuesday, he and Gov. Chris Christie told the feds they were willing to pay for part of a new trans-Hudson tunnel. They didn’t quite endorse Amtrak’s Gateway Tunnel project, and this may become a key point soon. But for two governors who haven’t show much willingness to support any transit project, this latest development is one we should welcome with open arms even if we need to maintain a healthy bit of skepticism about it.

In discussion his new-found support a few hours after sending a letter co-signed with Christie to the feds, Cuomo uttered one of the better quotes of this whole debate. “It is inarguable that the tunnel has to be built,” he said. “There’s only one tunnel now. It’s leaking. There have been significant delays because trains get stuck in the tunnel. It has to be done today. Everyone says that. Senators, congressmen, short people, tall people. Everyone says it has to be built.”

So as short people and tall people finally find a reason to come together, Christie and Cuomo have too. Their letter [pdf] is a thing of beauty. It’s the most conditional of condition support with so many conditions attached that their plan has essentially done away with Gateway without saying as much. As they say, “the obstacle to progress is funding,” and the two governors are finally ready to deal with what they peg is a $20 billion price tag. (Keep that number in mind and revisit Alon Levy’s August post on costs.)

The two wrote to President Barack Obama:

“We are writing jointly in an attempt to move the stalled project forward by putting a funding proposal on the table that we believe is realistic, appropriate and fair: split the responsibility for the cost. If the federal government will provide grants to pay for half of the cost of the project, the Port Authority, New York and New Jersey will take responsibility for developing a funding plan for the other half, convening all relevant agencies, and utilizing the proposed federal low-interest loan, local funding sources, and other funding strategies necessary to complement the federal grant commitment. This funding framework is comparable to previous structures proposed for a new tunnel.

Due to the nature of this project and to make it a reality on a timely basis, we would also need the federal government to expedite all environmental and planning approvals, as we will on our side. New Jersey will also make available all the planning work accomplished during discussion on the ARC tunnel.

At our direction, the Port Authority is prepared to take the lead in this effort, and is prepared to take Senator Schumer’s suggestion to create a dedicated staff and an entity within the Port Authority to develop such a plan and to get the right agencies and parties involved.”

Do you see this brilliance? Cuomo and Christie have completely twisted Schumer’s intentions to fit their Port Authority fiefdom. New York’s Senator had intentionally eschewed the Port Authority here and had called upon the states to create a new agency. Instead, Christie and Cuomo are willing to add a department to their favorite patronage body to funnel $10 billion in federal funds to their states. It’s the best sleight of hand since Keyser Soze surfaced only to disappear again.

Meanwhile, Cuomo and Christie — and then Cuomo later on in a press gaggle — pointed out numerous times that Amtrak’s ownership of the tunnels was a concern. If you read their entire letter, not once do they mention the Gateway Tunnel as the endpoint of this project. In fact, Amtrak is acknowledged only once, as the owner of the current tunnel, and as far as Cuomo and Christie are concerned, they can keep that tunnel. The northeast wants it tunnel and control of the project. “We assure you,” the two wrote to Obama, “that, if we have the funding, we will get it done. Our shovels are ready!”

Interestingly, as I noted, the word “Gateway” makes no appearances in this letter, but the two acknowledge the need to facilitate a northeast high speed rail corridor. The ARC tunnel, in the form of planning documents, makes an appearance, and I’ve heard some whispers that the New York and New Jersey delegations may wish to revisit ARC’s Alt G plan that saw through-running from Penn Station to Grand Central via dedicated tracks that could be used for high speed rail. It’s not a sure deal, but neither is Gateway as planned and conceived by Amtrak.

So today, short and tall people alike are cheering Christie and Cuomo for coming to the table. It’s barely an accomplishment, but it’s part of the way forward. Can the feds find $10 billion? Can New York and New Jersey find $5 billion each? The feds are ready to deal and say they will “engage with local officials immediately to initiate the work necessary to assign more reliable cost figures and eligibility for federal grants within existing programs.” Cuomo is no longer saying “it’s not my tunnel,” and that light at the end of the proverbial tunnel may be a watt or two stronger right now. There’s a long way, and at least $20 billion, to go, but this is a first step, albeit a very political one.

A derailment, a new station, and a feud over MTA capital funding

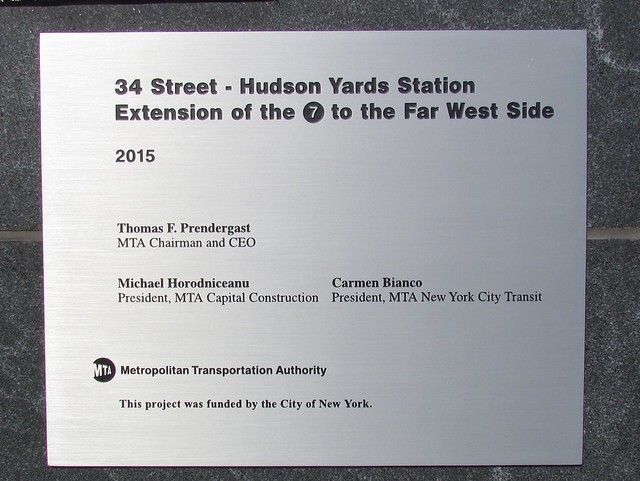

The city gave $2.3 billion for the 7 line extension, and now the MTA wants a similar commitment for the current capital plan. (Photo by Benjamin Kabak)

Over the summer, New Yorkers have witnessed a growing rift between Governor Andrew Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio. The two have different visions of government and can’t really find common ground on many issues. They undermine each other, often with Cuomo out-manuevering de Blasio, and as everything from affordable housing to Uber to the MTA have become opportunities for the two to stake out competing positions, city residents have been stuck in the middle of a rather childish fight that often reminds me of the tagline from Alien vs. Predator. Whoever wins, we lose.

This rift took center stage over the weekend, first following Thursday’s G train derailment and then again out in the open during Sunday’s 7 line extension opening ceremony-slash-political battle. As I mentioned in my coverage of the event, it was a very weird opening as everyone involved used the microphone to stake out a position on MTA funding. De Blasio and MTA Chair Tom Prendergast could have been less thrilled to see each other, and they, along with Chuck Schumer and Jerry Nadler and even TWU President John Samuelsen, spent the morning pointing fingers on the matter of the MTA funding. Praising Michael Bloomberg’s and Dan Doctoroff’s funding plans for the 7 line extension proved the perfect foil for de Blasio’s inaction on capital funding.

The MTA set the stage for this awkwardness on Friday afternoon when the agency issued a press release detailing the repair efforts for the G train and slamming the city at the same time. Prendergast didn’t quite blame the city for the G’s derailment, but he came as close as he could without pointing that finger directly. Here’s what Prendergast said then:

“Unfortunately, the regional consensus that has rebuilt the MTA is fraying. The MTA’s proposed 2015-19 Capital Program would invest $26.8 billion to renew, enhance and expand the transit network. We asked the State of New York to invest $8.3 billion, and Governor Cuomo agreed. But when we asked the City of New York to invest $3.2 billion, they offered only $657 million. The City’s contribution has fallen far short of the rate of inflation, much less real support for the $800 billion worth of MTA assets within the five boroughs.

“Our 2015-19 Capital Program allocates $927.5 million for repairing and rebuilding subway line structures, including bench walls such as the one involved in last night’s derailment. That’s more than double the $434.5 million in the prior program. But the MTA is barred by law from spending a single dollar on new capital projects until the state Capital Program Review Board approves our program – which can only happen when the City agrees to pay its fair share.

“I am tired of writing letters to City officials that result only in vague calls for more conversations. The sooner we can end these games and get to work on rebuilding our transit network, the better we can serve the 8.5 million customers who rely on the MTA every day.”

For what it’s worth, another Cuomo ally, TWU President John Samuelsen had a similar response. “This derailment is a glimpse of what the future holds for NYC’s Transit System unless the City steps up to foot their fair share of the bill for the MTA capital plan,” he said. “The system won’t fix itself, and for the sake of New York’s working families, the city must address this unfunded liability.”

On Sunday, Prendergast and Samuelsen repeated these arguments. Prendergast noted that 80 percent of the MTA’s “assets” are in New York City and asked for more support from de Blasio and his administration. De Blasio noted that city residents pay enough and that the MTA should look to Albany. “We pay 73 percent of the MTA budget through the city government’s contribution,” the mayor said, “through the fares our people pay, the tolls our people pay, the taxes our people pay. We are doing our share.”

All of this infighting is exhausting. Everyone is right; everyone is wrong. And as I wrote a few months ago, this battle is both the death and pinnacle of the MTA as an entity divorced from and integral to the politics of New York City and Albany. The MTA was created due to a lack of responsible city policies on transit, and the subways removed from the realm of electoral politics. The agency has been so thoroughly insulated from the political process by the machinations of Cuomo that it has, as a state agency, somehow come full circle. Why are we even looking to the city here anyway?

As Streetsblog, Ben Fried calls Cuomo’s politicization of the MTA “brazen,” but I think that’s too strong. Cuomo is simply exploiting the MTA to its logical extreme. The governor should definitely pinpoint how he plans to raise nearly $9 million for the currently-unfunded five-year capital program, but the city should contribute too. The city still is the legal owner of the subways, and the overwhelming majority of us who ride everyday are city residents, taxpayers and, hopefully, voters. It’s not unreasonable for the city to contribute to the capital plan as it does, via fares and taxes, to the operations side.

So what’s the way out of this mess? It’s easy for me to say the city should pay more, and it probably should. But it can do so very specifically by picking projects that benefit city residents. The city could earmark money for Phase 2 of the Second Ave. Subway or a Utica Ave. extension, and the MTA would gladly take the dollars without a further peep. Problem solved. Of course, this solution doesn’t begin to tackle the MTA’s runaway costs, and a blank check won’t fix this overarching problem. But that’s not de Blasio’s argument, even if it should be. Cuomo and de Blasio can fight this one out until the end of the year when the MTA has to start suspending capital construction contractors, but that just means we the riders lose. I don’t much like that future.

Scenes from the 7 line: A politically-charged opening

The 7 line’s new station at Hudson Yards, replete with massive mezzanine, finally opened on Sunday. (Photo by Benjamin Kabak)

For the first time since the last 1980s, the MTA yesterday opened a new station. The long-awaited 7 line extension from Times Square to Hudson Yards at 34th St. made its inaugural ride shortly after 1 p.m., but for a few hours during a bright blue morning, as politicians commemorated the day, the debate over the MTA’s future took centerstage. In the end, just about everything about Sunday’s opening ceremony for the 7 line extension was weird.

For now with infrastructure projects, New York is stuck in a weird place. Yesterday’s opening celebration was much ado about one new subway stop, something that would barely register a blip in cities around the world with developed transit networks, and yet, Sunday seemed like a release. Twenty-one months after then-Mayor Bloomberg held a pre-opening ribbon-cutting to slap himself on the back, the MTA finally let the public loose on its latest station, and except for a street-level elevator outage, with that new train station smell permeating the air, amidst a sunny day, everything seemed to run smoothly.

An R188 7 train, jammed with rail fans and locals, left Hudson Yards at 1:06 p.m. en route to Queens, and that was that. But underneath the clear skies and before the afternoon’s rain came, tensioned simmered. MTA CEO Tom Prendergast challenged Mayor Bill de Blasio, sitting a few feet away, to find $2.3 billion for the MTA’s capital plan over the next five years while de Blasio pushed back forcefully. Meanwhile, Senator Chuck Schumer and Rep. Jerry Nadler, both citing Mayor Bloomberg’s push to see the 7 line extended to the West Side, urged the city to pay up, and Schumer echoed a Sunday Dan Doctoroff Daily News column in calling for a station at 41st St. and 10th Ave. When their turns came, Albany pols seemed to want some resolution to the MTA’s capital debate, and TWU President John Samuelsen also used his turn at the mic to lay into the city’s lack of capital contributions. Governor Andrew Cuomo, meanwhile, was nowhere to be found. It wasn’t, after all, his party.

After the pols spoke, Dr. Michael Horodniceanu, head of the MTA’s capital construction unit, spoke on the design of the station. At one point, he mentioned how inclined elevators were first installed by Americans as part of the Eiffel Tower in the late 19th Century. It was an odd parallel to draw considering how the inclined elevators were one of the reasons why the station opened nearly two years late, and only City Council Member Corey Johnson noted that “it took long enough” to finally open the new stop.

I’ll take a look later this week at the evolving soap opera behind the capital campaign, But now, let’s journey underground into this vast, expensive new station. It’s very nice, and it’s very large. The inclined elevators are there for ADA compliance, and they’re so slow that the escalators are always a better option. The mezzanine reminds me of the giant, empty spaces that mark the IND stops in Brooklyn and Queens. There will never be enough people at the station to fill all the space, and as now, there’s no clear indication that the mezzanine will be anything more than just for show. The lack of columns leads to open views, and the lack of Transit Wireless service leads to more questions regarding cooperation among MTA contractors. (Reliable sources tell me the general contractor at Hudson Yards wasn’t keen to give Transit Wireless early access to the station. So cell and wifi service won’t be available for a few months.) All in all, though, it’s a subway stop. Take that for what you will.

Ultimately, this project will be known for what New York City got for its money. It’s a needed subway extension to an area of Manhattan previously inaccessible, but it cost $2.42 billion to get there. Sunday featured a lot of self-congratulatory speeches without a nod to the excessive costs or any indication that the MTA will have to rein in these price tags if it wants to realistically expand the subway system. In other countries, the opening of a new subway line is expected and a regular happening. In New York, it’s a monumental and costly undertaking that takes seven years to build 1.5 miles of truck and one subway station. Take that too for what you will.

Now, after months of waiting, the bulk of this saga is behind us, and New York City’s subway today has 469 stops, a temporary number on the way to at least 472. It was a beautiful day for a subway ride; the band played on; the art looks great; and there were cookies.

After the jump, a slideshow of photos from the day. These are from my Flickr album, and I’ve also posted a few to my Instagram account.

The quick G fix & MTA funding; the 7 line opens; weekend work on 14 subway lines

MTA workers repair the bench that led to the G train derailment. (Photo: MTA New York City Transit / Marc A. Hermann)

Following Thursday’s G train derailment, the MTA restored full service to the line by mid-afternoon on Friday, and then the fighting began. I’ll have much more on this next week, but in announcing restored service, MTA CEO and Chair Tom Prendergast let loose on the city and Mayor de Blasio for their lack of support for MTA financing.

The G, Prendergast noted, derailed when it came into contact with a deteriorated section of bench wall. The incident, by the way, was around 300 feet away from where Thursday’s earlier rail condition had occurred. Prendergast viewed this as a clear sign that support for the MTA’s maintenance is lagging, and he urged action. “I am tired of writing letters to City officials that result only in vague calls for more conversations,” he said. “The sooner we can end these games and get to work on rebuilding our transit network, the better we can serve the 8.5 million customers who rely on the MTA every day.”

Earlier in the day, TWU President John Samuelsen had issued a similar statement asking the city to pay more. Clearly, Gov. Cuomo had sent his allies to put pressure on New York City. Whether NYC should fund more of a state agency’s capital plan has become a hotly contested debate of late. More, as I mentioned, next week.

7 line opens Sunday

Until late last night, the MTA’s website had barely any mention of the opening of the 7 line extension stop at 34th Street, and it seemed weird. They should be plastering everything they own with this news, but they could be wary about drawing too much attention to the 21-month delay. Still, the 7 line is opening at 1 p.m. Sunday, and it’s the MTA’s first new subway stop in a generation. I’ll be on hand earlier in the day with photos. Be sure to check out my Instagram and Twitter accounts for updates. Unfortunately, Transit Wireless was unable to complete service installation for day 1. So the new station won’t be wired. I’ll have updates as soon as I have cell service.

For recent coverage of the 7 train extension, check out my posts. I look at the long lost stop at 41st and 10th, the now-bisected lower level at 42nd St. and 8th, the messy updates to the map, and future extensions to Chelsea or New Jersey.

Weekend work advisories for 14 subway lines

Now, after the jump, this weekend’s subway advisories, straight from the MTA. If anything looks wrong, take it up with them.

G train derails north of Hoyt-Schermerhorn; three injuries reported

Transti crews inspect the derailed G train near Hoyt-Schermerhorn Streets. (Photo: MTA New York City Transit / Marc A. Hermann)

A southbound G train derailed around 700 feet north of Hoyt-Schermerhorn Sts. at around 10:35 p.m. last night. The FDNY reported three injuries, though none serious, and approximately 80 passengers — a fairly empty late-night train — had to be evacuated. The MTA has said that the front two wheels of the first car jumped the track.

A southbound G train derailed around 700 feet north of Hoyt-Schermerhorn Sts. at around 10:35 p.m. last night. The FDNY reported three injuries, though none serious, and approximately 80 passengers — a fairly empty late-night train — had to be evacuated. The MTA has said that the front two wheels of the first car jumped the track.

As a result of the derailment, G train service will be limited with single-tracked service on the Queens-bound track only between Bedford-Nostrand and Court Sq. and “extremely limited” service between Fulton St. and Bedford Nostrand. The G is, in effect, now a shuttle. The MTA is urging riders to use the B38 along DeKalb or Lafayette Avenues as an alternate, and Transit is providing free transfer from the G at Fulton St. to the C at Lafayette Ave. and from the Broadway stop to Lorimer St. on the BMT’s J/M/Z lines. F service from Bergen St. south continues to operate normally.

The MTA is currently investigating the derailment, and while I have no basis for this conclusion, the incident follows a mid-afternoon rail condition near the same spot. According to MTA records, that issue had been cleared up a little after 5 p.m. on Thursday evening. More details to come.

CBC: MTA’s ‘State of Good Repair’ remains forever elusive

Over the past few/10/20/30/50 years, the New York City Transit Authority has engaged in an elusive game of repair. In transit-speak, the agency wants to achieve a state of good repair for its systems and stations, and although trains now run much more reliably than they did in the late 1970s and 1980s thanks to aggressive track replacement and signal work, our subway system’s stations are by and large in bad shape. As many have pointed out, attempting to achieve a state of good repair for a system with nearly 800 miles of track and a soon-to-be 469 stations is a Sisyphean task.

That Greek mythological figure is exactly how the city’s Citizens Budget Commission described the MTA’s effort in its latest report on the elusive State of Good Repair. Released last week, the report [pdf] essentially states what we all knew: The MTA is very unlikely to ever attain a State of Good Repair. Although that’s the headline, though, that’s not quite the main attraction. The MTA is never going to achieve a state of good repair because time keeps moving forward. A state rehabbed 20 years ago will need another overhaul in 15 years, and that’s just the unavoidable truth of a 35-year lifespan. The inefficiencies in the MTA’s progress though are dragging down the system.

More recently, the MTA has admitted that achieving a State of Good Repair is essentially impossible and has shifted to a component-based approach to station maintenance. This way, key elements such as staircases or platform lighting are repaired while other elements that may not affect the customer environment are left to the winds of time. This too has its problems as the CBC report details.

But enough of generalities. Let’s talk about the report. The CBC analyzed the MTA’s component-based approach and found that nearly a quarter of the MTA’s components are serious deficient, and 33 stations — including some high-profile, high-traffic ones — have less than half of their components in an acceptable state of repair. These include 7th Ave. on the Brighton Line and Grand Army Plaza (shown above), two of my local stations, and 16 in Queens, most serving the 7, N/Q or J trains.

With this in mind, the CBC asked if the MTA is allocating enough funding to its State of Good Repair efforts and what else the agency could be doing to speed up State of Good Repair efforts. I found their answers both frustrating and insufficient. For the first question, the CBC questioned the MTA’s prioritizing spending on expansion efforts such as East Side Access or Phase 2 of the Second Ave. Subway over repair works. To me, this misses the forest for the trees. If New York is to grow and remain competitive globally, it absolutely has to expand its high-speed, high-capacity transit network, and the only way to do that is through subway expansion. We can and have talked about the problem with these capital projects’ costs, but New York City can’t afford a future without an expanding subway network.

On the second issue, the CBC took a look at station repair costs, and it wasn’t pretty. Of the 42 station renovation efforts under the last five-year capital plan, 28 were over budget, and 10 saw their costs double. That’s setting aside the fact that the MTA accomplishes only 8 of these per year. Costs have increased at a rate that outpaces inflation, and the CBC, in so many words, notes that ADA-compliance often costs more than the benefits it delivers.

To achieve cost savings, the CBC urges the MTA to “make effective use” of public-private partnerships — which has proven easier said than done time after time. One of the CBC ideas — subway station conservancies modeled on the Department of Parks’ example. The CBC notes that “appropriate governance” would be required to avoid “inequities among neighborhoods,” but that has not exactly worked out well for the city’s parks. An adopt-a-station program would need aggressive oversight and some sort of redistribution scheme to ensure that those stations in Queens get the same investment as the ones in Midtown.

In a way, the CBC report though ignores what I mentioned earlier: The MTA cannot maintain and achieve a State of Good Repair, and the agency recognizes this. With 468 stations, the work is never-ending, and the MTA has to figure out a way to ensure that funding is sustainable and sufficient for a never-ending renovation scheme that considers a 35- or 40-year useful life. That is, if a station is renovated now, it will have to be re-done in 2050, and stations that were overhauled in 1995 are up for renovation again in 2030.

Meanwhile, the report has led to some interesting examinations of MTA funding schemes. Christopher Bonanos at New York Magazine asked if real estate developers should fund MTA repairs. Playing off of the One Vanderbilt investment in the Grand Central station, he urges real estate developers to pony up money for subway improvements and throws in the carrot of zoning variances or subway-level real estate:

Every giant glass tower that goes up in midtown adds a few hundred occupants (at least) to the grid. Each building increases the load on city services: water, sewer, electrical, transit. Setting aside the big transfer points like Times Square, a local midtown subway stop serves about 20,000 or so riders on a weekday. Add ten new apartment buildings in the neighborhood, and that number of users will go up by a significant percentage. If those buildings’ developers are relying on city systems, they should pay for their improvement. Every giant new tower, or group of towers, should be matched with a renovated station down the block…The MTA could even sweeten the deal by throwing in a lease on some of its own wasted real estate. Some of the giant mezzanine spaces of the A-C-E stations, for example, could easily garage a few shops. Chipotle and Starbucks probably wouldn’t want to be in the grimy stations that exist now — but in fresh, bright renovated ones? Why not? In exchange for building out the stores, the developer would get a share of the rental revenue for, say, a decade.

On the other hand, Rebecca Baird-Remba at New York Yimby cast a skeptical eye at P3s as a be-all and end-all solution for transit funding woes. She feels that New York State requires formal legislation overseeing P3s before the MTA could rely on them for serious transit funding, but ultimately, these one-offs are alluring.

All in all, it’s a tough balance. The MTA isn’t going to achieve a state of good repair, but station repairs should move faster than they do. Again, though, without a serious conversation on cost control and an aggressive cost-cutting initiative by the MTA, we will be paying more for less as the years go by. Even Sisyphus didn’t have it that bad.

For a map showing how your local station stacks up against the system’s worst, check out this interactive overview from the CBC.