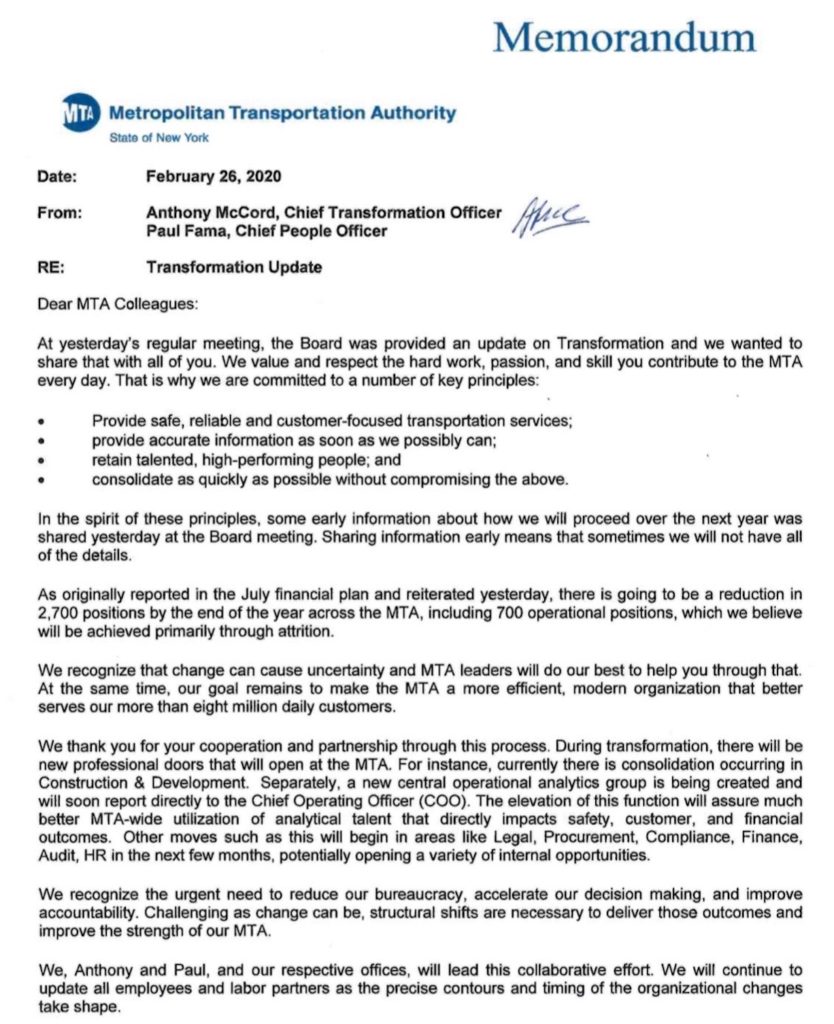

Gov. Andrew Cuomo ponders what it means to “disinfect” the subways during his Thursday briefing.

For the first time its in 116-year history, the New York City subways will no longer have planned 24/7 service as Gov. Andrew Cuomo and his MTA announced on Thursday that, beginning next Wednesday, trains will not run between 1 a.m. – 5 a.m. Overnight subway service — a New York City hallmark — will be suspended for the foreseeable future, and the MTA will continue to offer bus service or subsidize for-hire vehicle use for the 11,000 essential employees who now find themselves without late-night train service.

Why this is happening now and how the MTA arrived at this historic outcome isn’t clear. The decision to cut overnight service, made over the course of around 24 hours and without consultation or approval of the neutered MTA Board, arrives amidst an increase focus on homeless New Yorkers taking up residence in the subway and increased attention on the perceived need to clean subway surfaces to combat the threat of COVID-19. Yet, for a city used to relying on the subways to get around at any time of day, the official justifications for the move are frustratingly murky, and it’s not clear how the MTA will guarantee sufficient replacement service or when the agency will restore the overnight subways, a hallmark of the city’s non-stop economy.

The governor first announced the shutdown during his daily coronavirus press conference on Thursday. (The meandering transcript is available here.) The announcement came a day after the governor, waving around a tabloid story that displayed a homeless New Yorker covered in his own excrement and flashing an MTA operator the peace sign, challenged the MTA to improve cleanliness, and two days after Mayor Bill de Blasio asked the MTA to shutter 41 terminal stations overnight to allow the city to assist with homeless outreach (and removal). In a sense, it was the denouement of a fight that’s been raging for days, months and years. The city has failed to provide adequate and safe shelter for some homeless New Yorkers who are in desperate need of social services and, in many cases, psychological help, and those homeless New Yorkers have often fled to the subways. This was wrongly tolerated to a degree during good times but became a public health crisis as the coronavirus pandemic raged around us.

Essential workers were being forced to ride trains with semi-permanent homeless residents while the mayor refused to accept responsibility for the problem and the governor challenged the MTA to come up with a solution. As Julianne Cuba wrote on Streetsblog NYC yesterday, the crisis is a housing problem and not a transit problem, but still, the mayor and governor both seemed to expect a transit agency to address a societal problem it isn’t, by its nature, capable of addressing.

Is this about homeless? Cleanliness? When asked that question by NY1’s Pat Kiernan on Friday morning, MTA Chair Pat Foye first said, “No, this is about disinfecting trains.” But he immediately continued speaking at length about the issues the mayor raised. Foye continued:

“Obviously the homeless has become a significant issue and as the governor noted yesterday, there’s been rapid deterioration especially in the nighttime period on the subways. Yesterday Mayor de Blasio joined by Zoom, the governor in making and affirming and supporting this decision, but the City also committed a robust and sustainable NYPD presence to continue to help with the closing of the subway system from 1am to 5am, but also to continue offering services to the homeless and getting them shelters. The NYPD has really stepped up its activities in the last week and number of weeks, and that level of commitment is really critical to this to this effort and us being able to assure our employees, current riders and future riders that the system has been disinfected on a regular basis, every subway car, every bus, every station.

Either way, as Clayton Guse of The Daily News summarized on Twitter, “The governor is using disinfecting/cleaning as air cover for the wholesale removal of homeless people from the system.”

Gov, Andrew Cuomo announces the temporary end of overnight subway service as Interim NYC Transit President Sarah Feinberg and MTA Chair Pat Foye look on. (Photo: Darren McGee – Office of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo)

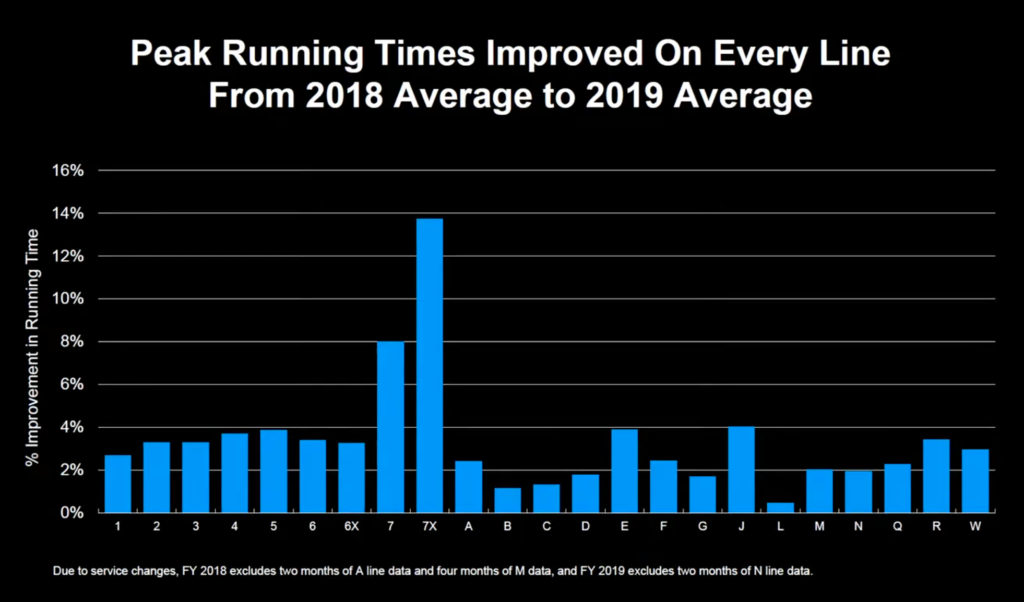

So what exactly is happening? According to the MTA’s numbers, only around 11,000 riders have been using the subway between 1 a.m. and 5 p.m., and most of those — 5,692, to be exact — have been using the subways between 4 and 5 a.m. So the MTA is going to kick everyone off trains for four hours supposedly to “disinfect” every car every day. “This is an unprecedented time and that calls for unprecedented action to protect the safety, security and health of our system for customers and employees. This closure will enable us to more aggressively and efficiently disinfect and clean our trains and buses than we have ever done before and do it every single day,” MTA Chair Pat Foye said in a statement.

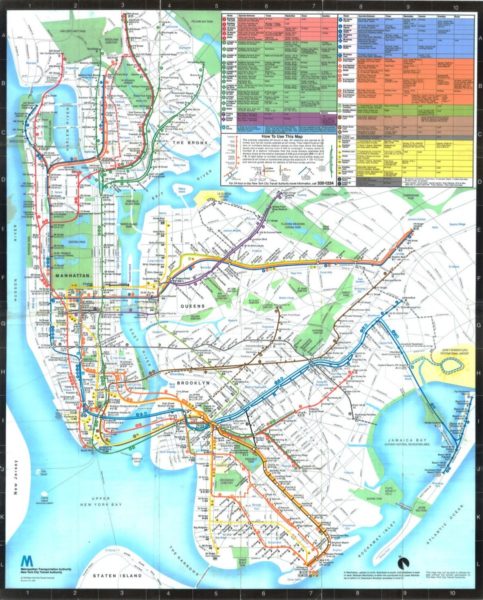

How — or if — the MTA will clean over 6400 subway cars every night in the span of four hours remains to be seen, but all 472 subway stations will close. According to the MTA, the city via the NYPD will be responsible for enforcing this closure. Does this mean homeless subway riders will be removed, forcibly or otherwise, from the subway system at 1 a.m. only to return at 5 a.m.? It’s not clear yet, but unless homeless riders are going to be detained, it seems likely. It’s also not clear how all subway stations will close without a massive amount of NYPD manpower as many do not have gates that lock and a good number no longer even have station agent booths eying entrances. The MTA has yet to share details regarding enforcement, but that’s not all we do not know.

We don’t know what the MTA’s new overnight “Essential Connector” service will be. We know that buses will still run 24/7, and an MTA spokesperson tells me that the agency will add bus service to respond to demand if certain routes are too popular for social distancing to be maintained. We know that essential workers with sufficient proof will be allowed two for-hire vehicle rides per night, but we don’t know how those will be ordered or how disinfectant standards will be maintained. We also don’t know how the MTA plans to disinfect its entire fleet every night. On NY1 on Friday morning, Foye stressed the bus service. The Essential Connector service, he said, “is going to be the full current bus schedule which will be supplemented as necessary. That’ll be the primary mode. These aren’t shuttle buses; this is regular bus service run by TWU members and other union members who are employees of the MTA, in this case New York City Transit. That will be the primary mode of moving between ten and eleven thousand passengers in the 1 a.m. to 5 a.m. period. That’ll be supplemented as necessary by livery cabs, by taxis, and by for-hire vehicles. But the primary method of moving those customers, between ten and eleven thousand, will be the bus service which will supplement as necessary and supplemented secondarily by livery cars, for-hire vehicles and taxis.”

By all accounts, this is still a work in progress with details to be announced ahead of next week’s launch. Already, though, as Jose Martinez reports today in THE CITYM, essential workers who have to commute overnight feel left out of the planning process and are scrambling for the alternatives they may have. It’s a bad situation all around.

But is it a necessary one? That’s the question looming over this, and after speaking with a few folks both within the MTA and outside of the agency, it’s not clear that the answer is yes. From a virology perspective, evidence is scant on surface transmission of COVID-19. The viral load doesn’t seem sufficient for transmission via subway pole in the normal course of a day, and disinfecting is only effective until the next person touches the surface. A rolling approach that maintains service would likely be sufficient.

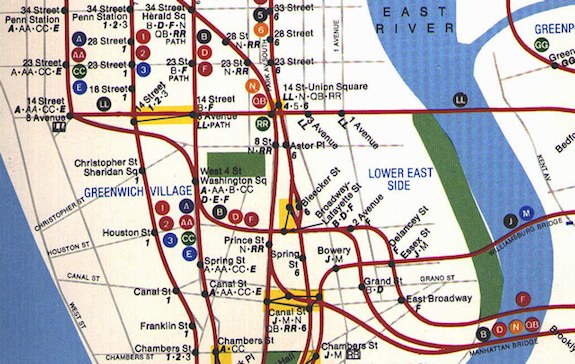

Most subway lines are operating on 20-minute overnight headways so train service is infrequent. At 1 a.m., for instance, the Q has four trains running to 96th and four heading to Coney Island. The MTA could disinfect other train sets earlier in the evening, take the Coney Island-bound trains out of service at Stillwell Ave., replace them in service with disinfected cars, and maintain 20-minute overnight headways for a fraction of the cost of shutting down the subways. This would alleviate all of the hassles and headaches late-night workers detail in Martinez’s article, but it wouldn’t address the concerns regarding homeless New Yorkers taking up semi-permanent residents underground. To that end, the city and state would actually have to address the myriad intertwined problems that lead to homeless New Yorkers taking up residence on the subway, and it’s much harder to address them during a crisis after failing to do so during the boom years.

The response from the advocacy community has been a mixed bag. Homeless advocates are not happy. In comments to Curbed New York, Craig Hughes of Safety Net Project said, “The Mayor and Governor continue to see homeless people as nuisances to be bounced from place to place, rather than full human beings who need housing. Rather than provide them with masks, hand sanitizer and other protective equipment, the MTA, Governor, and Mayor are opportunistically using the COVID crisis to move forward a long term goal of ridding the subways of people with no homes.”

Many transit organizations have called the governor’s decision “the right thing to do,” as the RPA did without offering must justification for that assessment. The Riders Alliance (of which I am a board member) struck a more forceful tone. “Even during a crisis, New York is and will be a 24/7 city,” Executive Director Betsy Plum said in a statement. “Governor Cuomo’s suspension of subway service must be strictly temporary while a longer-term solution is developed and implemented. And, in the meantime, the governor must ensure that riders have access to safe, reliable, and frequent replacement bus service.”

“Strictly temporary” is indeed the hope, but we don’t know when 24/7 subway service — a vital part of any recovery in New York City — will return. The MTA, in its release said, it “resume overnight service between the period of 1-5 a.m. when customer demand returns, and innovative and efficient disinfecting techniques have been successfully deployed systemwide.” This is a chicken/egg problem as customer demand won’t return if the service doesn’t exist, and in off-camera comments on Thursday, Interim NYCT President Sarah Feinberg said they expect the service suspension to last the duration of the pandemic. Again, it’s not clear what that means as Cuomo is likely to loosen some PAUSE restrictions in the coming weeks and months, but the World Health Organization likely won’t declare an end to the pandemic until well into 2021. Are we to go without 24/7 subway service for that long? Can the city survive without it?

State Senator Brad Hoylman doesn’t think so, and to that end, he announced that he will introduce legislation requiring overnight subway service to return “after any declared end to the pandemic.” But again, that’s ambiguous timing. Who gets to determine the end of the pandemic? Why can’t overnight subway service return before the end of the pandemic as life in New York returns to normal? Who can guarantee that the state and the MTA won’t use this period as a trial run to end overnight subway service entirely? These may be uncomfortable questions to ask amidst a pandemic, but transit is key to sustaining residents during the pandemic and will be a key part of New York City’s recovery. Uncertainty creates anxiety that undercuts the city’s future.

By now, I think you can see my skepticism toward this whole idea. Has late-night subway service become another pawn in the battle between the mayor and governor? I’ll let this tweet from MTA advisor Ken Lovett answer that question.

The mayor was looking to close the subway overnight to deal with the homeless issue, something we asserted wasn’t necessary. This is all about a more aggressive disinfecting program for essential workers https://t.co/MXSw5RWsUh

— ken lovett (@klnynews) April 30, 2020

Meanwhile, on Thursday night, cops (but not social workers) were sending homeless New Yorkers out into the rain. The subways need to be clean; the subways need to be safe; the subways should not be a home of last resort for the down-and-out; and the subways should not be viewed as a de facto homeless shelter by the mayor of New York. But the subways need to run, and they need to run all night. Cutting overnight service isn’t a decision that should be mad rashly over the course of 24 hours, and it’s a move that should come with a clear alternate service plan and an end date. Without justification or an analysis of alternatives that can guarantee both disinfectant procedures and subway service, this move seems to be governing via headline rather than rigorous, justifiable policy. For New York to succeed, the subways and its political leaders need to be in concert, and right now, they’re not as the City That Never Sleeps grabs a new-found four hours of shuteye every night into the future.