For as long as I can remember, I’ve been a fan of maps. I enjoy the way various graphical representations can serve to show the way a city works, and to me, it’s fascinating to see how map design impacts map usefulness. A schematic/diagrammatic map may show the best way to get from Point A to Point B without extraneous detail, but the extraneous detail may be necessary to get to path of travel from A to B. Essentially, there is no right way to present a map, but the philosophy of cartography and graphic design can heavily influence how a map is used by its intended audience.

In New York City, this debate centers around the subway map. Today’s subway map is not a work of great design, and it tries to be everything to everyone. New Yorkers demand a semblance of realism in their map and have long wanted major landmarks on the subway map. Tourists, meanwhile, seem to treat it as a navigation aid even though distances are distorted and few streets can be found on it.

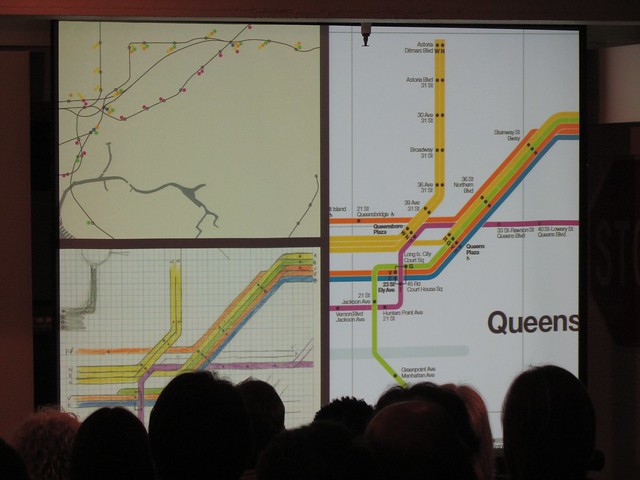

Over the years, New York has toyed when varying approaches to the subway map. Early IRT representations showed Manhattan on its side, and over the years, unified system maps ranged in form from geographic to abstract and bubbly to some mix of both. No map, of course, engenders more discussion or debate than Massimo Vignelli’s schematic — the only subway map in the Museum of Modern Art and the only one to start Internet commenting wars.

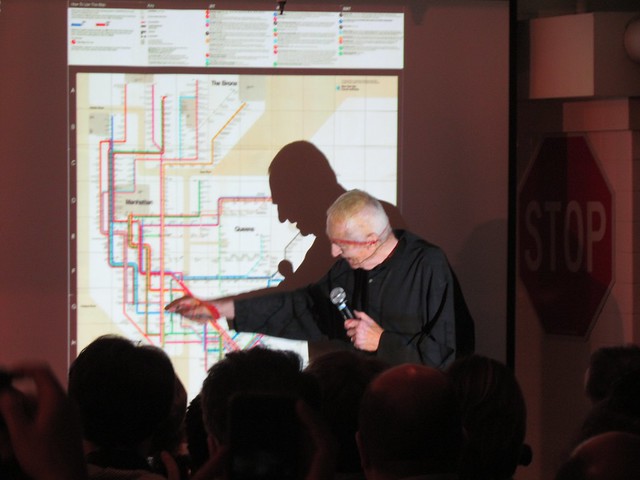

Over the past few years, Vignelli’s map has enjoyed a resurgence. Men’s Vogue sponsored an update in 2008, and MTA’s Weekender map has delivered Vignelli to the digital realm. The designer himself participating in a robust discussion on form and function at the Museum of the City of New York nearly two years ago. So with the Weekender’s arrival, it was natural for the Transit Museum to sponsor a panel featuring the 81-year-old Massimo Vignelli and his two younger associates, Beatriz Cifuentes and Yoshiki Waterhouse, who both had key roles in updating Vignelli’s map for the 21st Century.

By and large, the panel was about Vignelli, his map and his design philosophy. In an venture, he has tended toward crisp lines, sharp angels and minimalism. That is, in fact, what he did with his subway map that proved so controversial. For him, he explained on Tuesday night, the subway map should show what the subway does and nothing more. “Who cares if the subway has to go around like that,” he said during his talk, pointing to the curve Montague Street tunnel on the current map. The conductor drives the train while the passengers simply want to know how to get there.

Throughout the course of the talk, Vignelli made it perfectly clear that no one loved and appreciated his map more than he did, and that’s likely true for any designer. It took a forward-thinking MTA head in William Ronan to allow modern design into the transit authority, and it took another — Jay Walder — to bring it back for the Weekender. The problem with Vignelli’s map, though, isn’t its look; it’s the functionality.

As Vignelli admits, the now-iconic subway map, so evocative of a different era in American and New York City history, was supposed to be one part of a four-piece system. We know about the verbal map which explains that one must take the D to the F to travel from Atlantic Ave. to Forest Hills; we know about the neighborhood maps that show the area around the subway station. Vignelli mentioned on Tuesday a geographically accurate map that he never produced as the third piece, and of course, the map with its route lines and 45 degree angles as the centerpiece.

For Vignelli, simplicity is key. “Line, dot, that’s it,” he said. “No dot, no stop.” Had the designer had his way, the subway map he made would have been even more minimalist with no water, no parks and just a nod at borough boundaries. It assumes a level of knowledge with the above-ground world that is still required today.

Vignelli’s map always faced a lot of criticism though. The colors were too numerous, and some stations weren’t in the right place. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, he didn’t have GPS locations and precise station data, but still, it wasn’t quite right. The newest version corrects those flaws and simplifies the color scheme. Today, it’s in use as The Weekender, and Vignelli and his associates acknowledged how much better suited that map is to a digital realm.

With the need to show different service patterns at different times of the day, Vignelli believed digital maps are the future. “That’s why printing is dead,” he said. “It doesn’t make sense to print a map.”

Of course, there’s still a public part of Massimo Vignelli that wants to see his map return to greater use, and he admitted as much. As the MTA wires its stations and brings technology underground, the easy translation from the page to the web for the Vignelli map may keep it alive longer than anyone would have thought after it was replaced in 1979. “The Weekend should become the week-long official map,” Vignelli said. Perhaps, with the right changes, its time has come.

20 comments

Nothing on this neat article about the Barclays Transit connection? Or do you only cover negative articles about that?

http://www.nydailynews.com/lif.....-1.1159087

I hadn’t seen that article yet or the station. There’s nothing new in it, and I can’t steal copyrighted photos. You’ll just have to wait until I get in there on Monday after it opens.

Plus, not to get too defensive, but my coverage of the station itself hasn’t been negative. The mass transit upgrades, as I’ve said in the past, are tremendous. It’s the well below market value air rights sale that’s very problematic.

What does any of this have to do with Vignelli anyway?

What does Barclays even have to do with Vignelli’s philosophy on maps?

[…] Vignelli: Paper Subway Maps Don’t Make Sense Anymore (SAS) […]

Nice recap. Wish I’d been free to attend this myself.

Vignelli is not really responsible for his map having so many colors. The scheme of different colors for each route came into being with the 1967 map.

And the Transit Authority had been using schematic diagriams as its official map since about 1958. Vignelli just made it look nice.

Vignelli may have not been responsible for his map having so many colors, but he should have tried to convince the MTA to use a single color for each trunk line or a dark version of the color for express and light for the local. That way one wouldn’t have to remember so many colors since in many cases in Manhattan, you can use one of two or one of four lines. His map would encourage you to wait for just the gold line for example, when you could have taken any number of lines. The routes paralleled each other for distances that were too great to use more than one color.

His diagram was okay to figure out your route if you already knew your boarding and departing station, but without geography it was too easy to take the wrong route and get off at the wrong Kings Highway and be nowhere your destination. We really need one map for the stations and another for the subway cars.

I was at that lecture too and generally enjoyed it very much, though I have to disagree a bit with the “print is dead” comments. I think it’ll be a while yet before technology is cheap enough for the cost-benefit of switching out the map in every car for a digital display makes sense.

As a web designer I feel I should also mention that, while I’m a huge fan of the new Vignelli diagram, the Weekender website suffers from a lot of the classic pitfalls of graphic designers trying to design for the web: fixed width layout, excessively bespoke map navigation, and too much animation.

The technology is already there, no? FIND displays offer dynamic routing information. You still need a way to show the paths of trains that riders aren’t on at that moment.

The overall point though is a good one: The current version of the subway map shows service patterns for about 8 of the day’s 24 hours. It’s not particularly useful/accurate most of the time.

The FIND signs still has a lot of limitations, one example: up-to-minute information, especially on the weekends which is so useless.

Why not both? Put the functional schematic Vignelli on one side and a geographically accurate one on the other? It doesn’t have to be either/or. If you feel like the separate line and schedule info is useful, then put them on the side split between the two faces.

In the subway cars, alternate which one faces out.

Okay, now that sounds a little arrogant. The people who use the system clearly care, which is why his map ultimately failed. One can argue it would be nice if they didn’t care, but they clearly do.

Besides, the conductor doesn’t drive the train; the train operator does.

The maligned Montague St curve (and all the other irregular curves) serve a real navigational function. If a map has nothing but right and oblique angles, how do you distinguish one from the other when trying to quickly locate a station?

It seems to me that a good schematic map will always be best at making it clear how to get from point A to point B most easily and efficiently. But it will not necessarily shed any light on where point A and point B are located in the real world, so many users won’t even get to the stage where they’re able to look for the best route between A and B. Imagine, for example, that each station on the Vignelli map was labeled ‘station 1’, ‘station 2’, all the up to ‘station 421’. It would be totally useless for all but a few cognoscenti who had already memorized the topology of the system.

In parts of the city, that problem is solved. A station identified as 42 St/6 Av is blessed with a unique set of coordinates that tell EXACTLY where it is in relation to any other point in the same coordinate system. Of course, not everyone is familiar with that coordinate system, or the analogous ones in Brooklyn and Queens. And many stations lie outside of any coordinate system (where is Winthrop St & Nostrand Ave in relation to Montrose Av & Bushwick Av?).

But a map that can make this clear will be bad a showing how to navigate the system. I find myself agreeing more and more with those advocating the two-map solution.

This:

…and this:

…are non-compatible statements. Comer the day that color LCD displays are cheap enough the MTA can put two per car and 1-2 in each station that can interactively change according to time, date and the interest of the person looking at the map, then you can have a quasi-schematic route map assisted by other maps that won’t annoy the hell out of most people who need a functional diagram. But you can’t have a ‘simple’ map that then requires the assistance of 2-3 other maps to get the unsure subway user from their origin point to their destination.

People nowadays get mad if their Netflix movie takes more than five seconds to start streaming. You’re not gonig to get them to use multiple maps to find their way around New York unless or until you can just punch a button on your iPhone and change from Vignelli’s abstract route design to another map that actually gives a damn about where you end up in the real world.

I don’t disagree with you, but let me play devil’s advocate for a second here. First, Vignelli was talking about simplicity in design, not necessarily simplicity in use. That’s an underlying issue with his map.

Second, why shouldn’t we expect people to use different maps for different functions? If I’m traveling from New York City to Washington, DC, I use one map to get myself from DC to NYC on the interstate and another to get myself from the interstate to my final destination. We’re used to, these days, having all of this on our phones, but for decades, that’s how we all had to navigate, and when I travel abroad, it’s still how I navigate, using a subway map for subway travel and a surface map for street navigation.

I agree it’s actually easier today to institute Vignelli’s original “4-for-1” mapping plan, since Google already kind of does that with their map app that shows standard mapping, satellite images and other options in-between. Punch a different button, get a different depiction of the same general area.

It’s easier to carry a smart phone or iPad with those options than multiple fold-out maps, or have to go to spot X at a station to see the neighborhood maps. New technology makes the option of using Vingelli’s map more viable than 40 years ago, but for him to continue to call his plan ‘simple’ comes across as someone who views his creation as the map for people who either don’t need a map to begin with, or are not in a hurry to get to their destination and have time to review the various mapping options. New Yorkers not in a hurry is close to an oxymoron, and explains why the map found favor with art aficionados more than it did with subway riders.

Does it make sense to try and replicate old technology using new technology? While that is always step one when a newer technology becomes available, the real advances occur when the new technology is allowed to break from the old.

What a smart phone or tablet can do is show how to get from point A to point B without the 99% of the system that is irrelevant. If a trip involves one line, or even two or more, those – and only those – need appear on the “map”. Why on earth would the information content need to be supplemented by all the other lines making up the subway system? So first tell where you are, then where you’re going, and then see the route.

For those of us who love maps, any sort of map has its virtues, but for getting around the city, YOU NO LONGER NEED A MAP!

There’s a Q&A with Vignelli from a design conference a few days prior, available here for $5. It comes with a 5-minute preview, where he touches upon the map. The host of the conference, Brand New, is a great blog with reviews of the branding/rebranding of corporate logos, just as this one is great with NYC transit.

[…] was key to Vignelli. During a 2012 talk at the Transit Museum, Vignelli spoke of his philosophy while heaping criticism on the current map. […]