Very quietly last month, the MTA released their 2019 ridership tallies, and last year was a good year for the subways. After three years of declining ridership, annual subway ridership hit 1,697,787,002, a jump of nearly 18 million or a hair over 1 percent above 2018’s total. Usually, the MTA would celebrate increased ridership and increased fare revenue, but with things being as they are right now, the release of these numbers was a muted one.

Ultimately, the L train work that reduced weekend service frequency along the 14th St. corridor likely cost the MTA a shot at 1.7 billion passengers, and if fare evasion was really as prevalent as the MTA has tried to claim it is, the subways last year may have been more crowded than they’ve ever been. I’m not quite sure that passes the smell test, but I digress. All in, 2019 was a positive step forward for the MTA, a rare spot of good news amidst the onslaught of bad these days. Whether the city will ever get back to these lofty subway ridership numbers in the COVID Era depends upon more than just the development of a vaccine.

2019 In Review

As subway ridership has cratered amidst the coronavirus pandemic, it feels weird to talk about crowded trains and increased ridership, but let’s take a look at the numbers. The gains were fairly evenly split between weekdays and weekends, a positive sign for Saturday and Sunday service which had been bleeding riders for years. An average 2019 weekday saw near 5.494 million riders, up from 5.438 million in 2018 while combined weekend ridership was slightly above 5.494 million, up also from 5.438 million a year before. Saturday gains outpaced Sunday with an average Saturday witnessing an increase of 40,000 riders while Sundays saw an increase of just 14,500 riders.

Outside of the way the L train rejiggered ridership across the G, J and M trains, the city’s newest subway stations saw some of the largest gains. The 7 train’s terminal at 34th St. and 11th Ave. saw ridership jump by 75% to 18,875 per day as the Hudson Yards development took shape and the Vessel and mall opened. Total weekday entrances at the three Q stops along Second Ave. increased by around 2500 per day as well, gains that outpaced the overall jump in subway ridership by a few percentage points.

The L train work, meanwhile, cut into the MTA’s push for 1.7 billion riders, but declines weren’t quite as steep as I would have expected. Average weekend ridership for the L train stations at 1st and 3rd Avenues in Manhattan declined by approximately 50% while stops through Williamsburg and Bushwick saw declines between 40-50 percent. Straphanger traffic into Bedford Ave. dipped by only 36 percent, and it was still the 39th busiest weekend stop last year, an impressive showing considering the paltry headways. Meanwhile, the Lorimer/Metropolitan L/G station saw a decline of only 3.7 percent, and G train stops in South Williamsburg and Greenpoint saw increases in weekend ridership of around 25 percent.

Other lines expected to carry the L train’s slack did indeed do so. Nearby station along the J and M lines saw weekend demand in excess of 50% above 2018 levels, and all in, the various mitigation efforts worked. Overall, the subways lost around 20,000 weekend entrances due to the L work, but nearby lines certainly saw an uptick in usage. (The L train worked formally wrapped in late April, and I wrote a postmortem on the L train project.)

2020 In Preview: A Spike Before the Cliff of the Pandemic

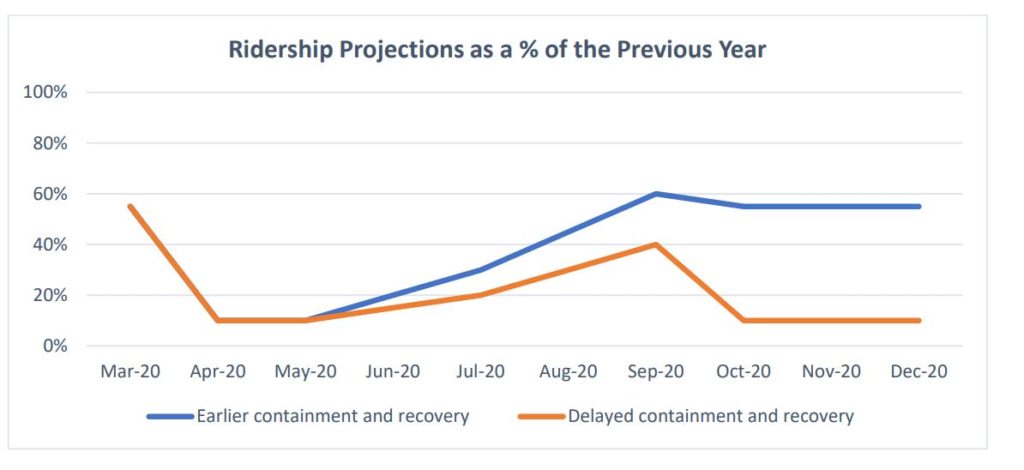

After this rosy 2019, things were looking up to start the current year as well. As the MTA reported in its board materials and on the release trumpeting last year’s ridership, “This upward trend in ridership continued in January and February of 2020, with both months outpacing January and February in 2019.” But nature in the form of COVID-19 is having its way with the world right now, and as shelter-in-place orders have slowed down the pace of life in New York City, only around 400,000-500,000 riders per day are using the subways, a 90% drop in ridership hard to contexualize. In a letter released last month calling for an additional $3.9 billion in federal aid, the MTA included a report prepared by consultants at McKinsey & Company detailing expected ridership levels over the remainder of 2020. The chart is an ugly one:

The MTA has yet to release an updated version of this chart, and already, even these pessimistic assumptions look too optimistic. The New York City area isn’t likely to see a loosening of the state’s PAUSE restrictions until early June, and the “delayed containment and recovery” track where ridership reaches 40 percent feels far more likely than the trend line anticipating 60% of riders returning by September. Whether we’ll be back at 5-10 percent of ridership and in another lockdown situation by the end of the year will depend upon a second wave. Even without another wave, the MTA is looking at a lost year of ridership, and even if everything breaks right for the city, the optimistic trend line contemplates only around 55% of riders will return this year. What if, as The Times speculates today, few people go back to work? While I am skeptical of the long-term trend, in the short term, Manhattan offices are going to be empty, and the days of 1.7 billion annual riders are going to be nothing but fond memories for the foreseeable future.

The question lingering over all of this involves the future. What happens next? Even the McKinsey analysis punts on that question as projections include a wide range of options and end in December. Subway ridership isn’t going to come back on January 1, 2021, and after receiving $3.8 billion last month and asking for an additional $3.9 billion, the MTA now says it will need at least $10.4 billion by the end of 2021 to stay afloat. Forget the $51 billion capital plan and the long-desired federal contribution; the MTA needs these dollars to stay solvent during a prolonged period of low ridership. Without it, they – and the city – are sunk as the bills pile up.

“Our request has garnered substantial bipartisan support as it did in the first round,” MTA CEO and Chairman Pat Foye said this week. “This is not a red or blue state issue; it’s a no brainer. The COVID-19 pandemic has made clear the importance of public transportation, during the pandemic and as part of the economic recovery when the pandemic subsides.”

But the recovery isn’t just economic. The MTA has to make people feel that transit is a choice that will not jeopardize public health. Already, the agency has had to contend with spurious claims such as those put forth in an MIT report that the subways spread coronavirus. Both Alon Levy and Aaron Gordon burned plenty of pixels debunking and contextualizing the argument. I don’t buy it either, but while we learn more about the transmission of coronavirus via droplets spread in contained spaces without sufficient ventilation, the subways can seem daunting. That is, in part, why the Governor ordered the end of 24/7 subway service (though we should be skeptical of those claims as well, as I wrote in a Patreon post last week).

Still, making the subways appealing is going to be costly. The MTA will have to maintain the appearances of cleanliness, through an aggressive cleaning and disinfecting program currently underway. This program has no price tag yet, and the agency hasn’t released any sort of scientific assessment indicating how long trains stay clean or disinfected after customers board to touch everything. We’ll have to get used to masks, gloves and a lot less singing on the subways. A contact-less fare payment should help too, but the OMNY rollout is still on pause due to the response to the virus. Until there is a vaccine, most New Yorkers are likely to view transit with skepticism, and I can’t say I blame them. The geometry of cars and the geography of New York City will likely help avoid the carmageddon we fear, but the MTA’s rider-dependent finances won’t improve unless and until ridership climbs and ridership won’t climb if New Yorkers aren’t comfortable on crowded subway trains.

Glimmers Of Hope Down The Line

Left unsaid in my ramblings today about the ridership figures is the impact of New York City’s most popular British import. The 2019 and early 2020 numbers were a testament to Andy Byford and the results he produced. By focusing on improving subway service and by focusing the public conversation on the actual improvements, riders returned to the system. The one percent increase during a prolonged period of L train service diversions is a true success story, and the building blocks are in place for the MTA to build on that success in a post-COVID Era. The problem will be one of revenue, from the feds who can rescue the MTA and save the economic lifeline of the city as the riders start to trickle back, and one of time. A year from now, when the MTA releases the 2020 ridership numbers, the picture will be grim, but we can hope now that things go up from there.

21 comments

My main concern about this subject relates to the fact that many people will be so shell shocked by this virus they may not return after there is an effective means to prevent it. This is a form of mental illness that combines paranoya, agoraphobia & germaphobia & will exhibit it self as “why should I go out if I can work from home, get everything I need delivered & besides the world has become dangerous as you cant tell who is sick & who isn’t.”

We’ll see in a few months if this will be the case & I would love nothing more to be wrong here.

1. Known fact: the virus is spread more in confined areas.

2. Observable reality: the subway is a confined area (plus it’s dirty, plus people live and excrete there)

1+2=?

So are taxies & when was the last time one of them was ever cleaned?

Well, if the government required all taxis to be closed once a day to be cleaned, that would be a reasonable response. Ben and Alon seem to be claiming that even though a subway is a place where us masses are confined together with homeless people who can’t practice personal hygiene, it doesn’t present an increased risk. Which is insane.

I probably should’ve not bothered with the MIT study and the responses. The MIT study alleged that the subways were why the virus has been so bad and deadly in New York, and that doesn’t seem to bear weight under scrutiny. It’s a different question regarding increased risk and personal safety – which I am not disputing right now.

If the MIT study came from almost any other university, it wouldn’t have received the same level of attention. It’s only because it is MIT & the fact it is cannon fodder for those who are anti transit, that anyone even noticed it in the first place.

1+2= MathIsRacist

I’m curious whether the MTA will proceed with their order of open-gangway subway cars which were intended to increase train capacity. Is it safer to have subway cars without open gangways to reduce circulation of infectious agents? Can open-gangway cars be converted at-will to closed-gangway cars if necessary?

Yes I believe the open gangway cars are in production. Also keep in mind with social distancing, open gangways will allow crowds to stretch out more freely.

I’m not sure I understand how airbourne COVID-19 is (still). The original WHO position was that it was not airbourne, but it seems that position was reversed a while ago.

My current understanding is that it is airbourne for modest periods of time (perhaps a few hours, in extreme cases). Somebody coughing/sneezing/breathing perhaps can infect people within a certain radius for a period of time. My understanding is that the size of the mucous droplets would of course be tiny, measured in a few micro-meters (?m), so while easily inhaled in close proximity, they are also relatively heavy drops of liquid that are probably not prone to staying in the air for long periods.

Regarding open gangways, perhaps it’s better to simply filter the air, and open gangways might make that easier? Perhaps less enclosed is always better than more enclosed?

Anyway, the main threat to the transit user seems to be surface exposure, and those ?m-sized droplets evidently do land on surfaces where they remain a threat.

You have to wonder how many people will continue telecommuting working from home and never return to the office using the subways. Too bad former New York City Transit President Andy Byford was not asked to come back and help out during this ongoing crises

(Larry Penner — transportation advocate, historian and writer who previously worked 31 years for the Federal Transit Administration Region 2 New York Office. This included the development, review, approval and oversight for billions in capital projects and programs for the MTA, NYC Transit bus and subway, Staten Island Rail Road, Long Island and Metro North Rail Roads, MTA Bus, New Jersey Transit along with 30 other transit agencies in NY & NJ)”..

I never thought that I would see subway and bus ridership was this low for a long period of time. I also never thought that Larry Penne would limit his comments to TWO sentences. Man, we live in a strange world! Now, if the lions start walking down Times Square in broad daylight – we are doomed! (LOL – Smile)

“Now, if the lions start walking down Times Square in broad daylight – we are doomed! (LOL – Smile”) For Matt Stafford that maybe an improvement.

I am more optimistic.

Public fears are based on an exaggerated level of personal risk. We know a lot more about this virus than we did in March and April when things looked truly bleak. We have a much better understanding of the risk profile for severe disease, and the rational conclusion is that this disease doesn’t pose a significant risk of severe disease or death to the average working age adult.

Certainly SARS-Cov-2 and COVID-19 can pose a grave risk to people with whom working age adults come in contact, including family members and loved ones, and any strategy must have as its primary objective the integrity of our healthcare system, that interconnected web of hospitals, clinics, etc., but life in a dense city has always come at the risk of infectious disease. It did when the subway was built, and its presence within living memory dates to the flu pandemics of the mid 20th century.

The public will take time to adjust, but most people are fundamentally rational and will gradually come to assume slightly increased risk of exposing vulnerable people in exchange for a return to something resembling a New York worth living in. We’ll wear masks, wash our hands, keep our distance…for a time, but eventually there will be a return to normalcy. When that happens is anyone’s guess, but this forecast seems far too pessimistic. No expert can credibly claim to model public or corporate acceptance of risk, because a New York of this scale and interconnectedness has never a threat remotely like this. It seems that this analysis is dressing up subjective assessments and prognostications as objective, mathematical certainty.

I’d venture to say the only certainty here is that after the events of the past few months, we’ve all had just about enough of that.

how much does it cost to replace a toyota camry hybrid battery

Kado Bar is the undeniable choice for Vape because of a variety of reasons.

Kado Bar is the undeniable choice for Vape because of a variety of reasons. With a track record of quality and innovation, Kado Bar consistently delivers high-quality products.

Five stars for this content!

Really loved the insights you’ve shared here! Your content is always detailed and easy to follow. I’ve recently been exploring portable hookah pen and your blog gave me some fresh perspectives to consider. Keep up the great work—looking forward to reading more of your posts!

Really loved the insights you’ve shared here! Your content is always detailed and easy to follow. I’ve recently been exploring Olit Hookalit S 35000 and your blog gave me some fresh perspectives to consider. Keep up the great work—looking forward to reading more of your posts!

Such an insightful and well-written blog! I really appreciate the way you’ve explained the details—it makes the topic so much easier to understand. I’ve recently been exploring OXBAR Flavors and your content gave me even more clarity. Keep up the amazing work, and I’ll definitely keep reading your blog for more valuable insights.