With his NYC Ferries as a backdrop, the mayor announced only 20 miles of new bus lanes to keep the city moving as NYC starts to reopen. (Photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Did Bill de Blasio prove me wrong? Of course not; that’s a rhetorical question with an obvious answer. But just a few hours after I wrote about his lack of plan to accommodate transportation amidst New York’s reopening, the Mayor unveiled 20 miles of new busways and bus lanes that will be added to city streets by October. In doing so, Bill de Blasio managed to fail to meet the MTA’s request by two-thirds and the city’s borough presidents’ by 50 percent. He missed a prime opportunity to drastically reshape miles of city streets amidst an ongoing pandemic where giving people more space is of utmost importance, and while better than nothing, de Blasio’s plan is the bare minimum any mayor could have done. And, oh, the mayor announced, as an aside meriting one sentence of his time, that the 14th St. Busway is now permanent.

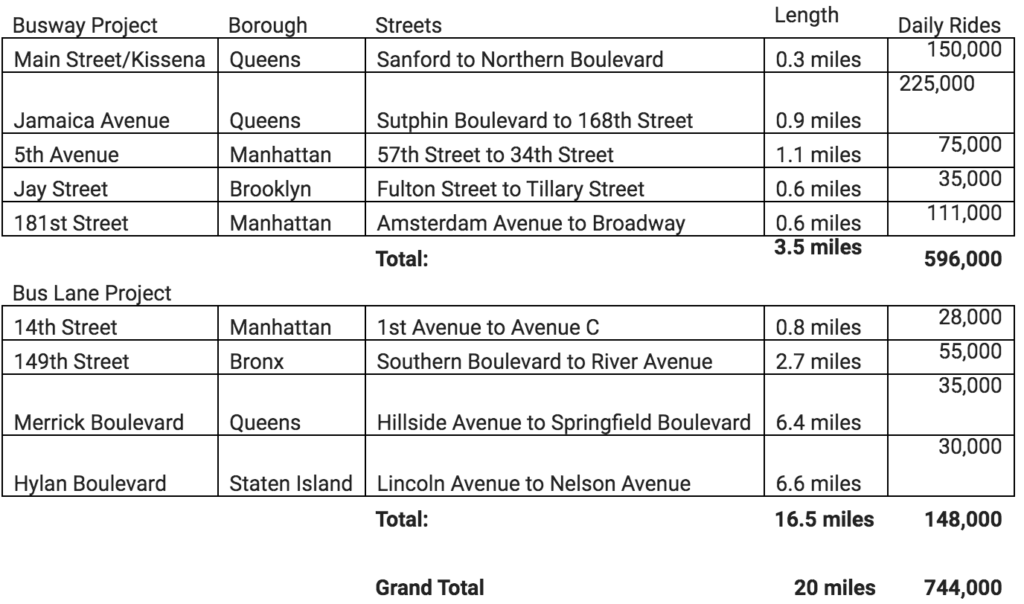

First, the details, in handy chart form.

As you can see, the city is getting 3.5 total new miles of busway treatments and 16.5 miles of new bus lanes. The ridership numbers are a bit fudged as, for instance, the end-to-end daily ridership of the M14 was 28,000 before the pandemic, and the 0.8 mile segment from 1st Ave. to Ave. C accounts only for a portion of that. Still, during his comments, the mayor spoke about improving bus service for 750,000. Each rider will benefit from better service, but bus prioritization along only parts of some routes mean most riders will never experience the difference.

As to timing, these lanes will roll out month-by-month through October. The Flushing busway and bus lanes along 14th St. and 149th St. will arrive in June, followed by the Jamaica Ave. and 5th Ave. busways and Hylan Boulevard bus lanes in July. August will see a busway enter service on Jay St. and bus lanes on Merrick Boulevard while the 181st St. busway isn’t due until October. The mayor said the busways will be “similar” to 14th Street, and his press release talks about offset bus lanes in other places. But if similar to 14th St., the busways will still allow cars for a block at a time and the successes will rely heavily on enforcement, whether in person or automated. That’s the plan; let’s get to the thoughts.

The Mayor is still talking past the MTA

Last week, the MTA asked for 60 miles of bus lanes throughout the city. They have to ask because the city controls its own street space, and their request came a few weeks after the city’s cadre of borough presidents requested 40 miles of lanes. The mayor responded with 20, and his lanes and the MTA’s own requests hardly seem to align.

Here's how the city responded to the MTA's request. They're just continuing to talk past each other.

? E 149th

? E.L. Grant

? Tremont

? Fordham Rd

? University? Flatbush Ave.

? Bay St.

? Richmond Terrace

? 181 St.

? Main Street? Archer Ave

? Livingston St.— Second Ave. Sagas (@2AvSagas) June 8, 2020

Many of the bus treatments the mayor announced yesterday weren’t even among those requested by the MTA, and even more confounding is how thoughtful the MTA’s request was. DOT, for instance, has bus lane designs for E.L. Grant and University Ave. on ice, just waiting for the go-ahead to proceed. The MTA seemed to be considerate of DOT in making its own request, but the mayor hasn’t responded in turn. When asked by Streetblog NYC’s Gersh Kuntzman about the differences between the MTA’s request and the city’s plan, the mayor responded by not answering the question:

I’m someone who likes to see progress and celebrate progress and then keep making more progress. So my attitude is this is a major step. The fact that we have proven in a way that – you know, the history probably better than me. I don’t think a busway like 14th Street was successfully achieved previously in city history. Maybe I don’t know my facts, but I think I’m right. The fact that today we’re saying 14th Street is now permanent, five more coming in. It is the beginning of something really positive, obviously between the busways, the Select Bus Service, all of these approaches have been working and that opens the door to a very positive future for New York City. And this is a great time to do it because we got to give people confidence to come back to mass transit. So we’re going to do everything we can do, but we’re always going to tell you what we think we can do right now. And then as we see the next opportunity to do more, we’ll of course do more.

It’s a fine answer for a run-of-the-mill Monday three years ago but one that falls apart under scrutiny in the midst of a pandemic.

A Day Late and A Few Months Slow

To that end, why did the mayor wait until Monday morning, hours after the city entered Phase 1 of the restart, to announce new bus treatments? The timing of this announcement shows a lack of urgency on the part of the mayor and the frustration the city has felt with his lack of plans. The time to announce post-PAUSE busways and bus lanes was April, when city streets were empty, and New Yorkers knew they needed more space on transit. Buses, after all, have remained popular throughout the past few months. The city then could have used April and May to implement these lanes so that they were serving essential workers during lockdown and in place as restrictions lifted. That’s what every other city has done, but instead, we’ll get a few lanes this month and a few more by the end of the summer. If we’re in the middle of a public health crisis, you would never know it from the mayor’s slow and deliberate approach.

‘New York City can have a little busway, as a treat’

While route miles are not always strong indicators of quality, the mayor’s plan is diminishingly small. With approximately 6000 miles of city streets at his disposal, the mayor has opted to put busways on 3.5 of them and buslanes on another 16.5, for a grand total of 0.33% of city streets. Under this perspective, even the MTA’s more expansive ask represents only 1% of city streets, and we should be thinking even bigger right now. Simply put, there is no vision to reimagine street space; these are just scraps under the table of the private automobile which has long dominated the way we allocate public space in New York City.

That said, these lanes are good starts. We have long needed bus lanes across 181st Street, and untangling even just 0.3 miles of Flushing would do wonders for a heavily-congested area. As Transit Center noted, “Short busways can make a big impact if they carve a path through intense traffic congestion.” Still, these short treatments that well-run city would have implemented four years ago seem far too meager for the moment. Brooklyn, after all, a borough that is a city unto itself with 2.3 million people, is getting all of 0.6 miles of a busway as close to Manhattan as possible. This does very little to facilitate travel across greater distances.

Feeder Routes Amidst a Pandemic

Along with the distances is the problem of design. Generally speaking, we want to design transit in this COVID-19 moment to encourage dispersed usage. We want more people on buses so that subways are emptier and social distancing easier. By and large though, these new bus lanes bolster the feeder-route nature of the city’s bus network. The Flushing treatment, for instance, makes getting to and from the 7 train easier, as does the 181st St. route, but outside of destinations in Flushing or for NY-Presbyterian-bound commuters, these new lanes do little to get people from where they live to where they work without relying on the subway. What we need is a massive temporary re-think of the bus network that enables interborough connections in ways the current bus network doesn’t. That’s not a de Blasio per se, but the current crisis exposes and exacerbates the limits of NYC’s bus network.

Getting the mayor to commit to transit is always a fight

The mayor makes improving transit in New York City an exhausting fight. For months, advocates, politicians and even the MTA called for more and more busways and faster. The mayor finally relented, and when he did, it was to grant everyone a fraction of their initial requests. So the politicians and advocates have to line up to issue their praise and then continue fighting for even more miles of busways. This is how the mayor, who ran on an agenda of equality, treated Fair Fares: He refused to embrace it and then did the bare minimum when forced to. It’s exhausting for everyone involved in the advocacy and planning, and it’s no way to run or improve a city.

The mayor had an opportunity to think big, help New Yorkers get around faster and more efficiently during a pandemic, and he did the bare minimum weeks too late. If that’s not Bill de Blasio’s transportation approach in a nutshell, I don’t know what is.

Buses are certainly having their moment these days. With the launch of the 14th St. Busway, we’ve seen a

Buses are certainly having their moment these days. With the launch of the 14th St. Busway, we’ve seen a