Once upon a time, the new South Ferry Terminal was due to open in early 2008. It’s now the end of January 2009 and a good six weeks since I went on a tour of the new terminal. At the time, Michael Horodniceanu, the president of MTA Capital Construction, told the gaggle of reporters that the new station stop would open by early January. Now, in his piece on the Fulton St. hub, Bobby Cuza notes that the station opening has been delayed due to final testing. Shocking, I know. An announced opening date could come later this week.

MTA Construction

Inside the new South Ferry terminal

Sometime next month, the MTA will, for the first time in twenty years, open a new subway station in New York City. The new terminal at South Ferry — the first post-9/11 redevelopment project to open in Lower Manhattan — features a fully ADA-compliant two-track station with wide platforms and state-of-the-art engineering. It will offer up a connection to the R and W trains at Whitehall St. and will serve as the station of the future, a prototype of sorts for the three stations planned along Second Ave., and it looks great.

Yesterday, Michael Horodniceanu, the president of MTA Capital Construction, led a group of reporters and photographers on a tour of the not-yet-completed facility, and I was lucky enough to get an invite. Let’s take a tour of the new station. (All links go to my flickr photo set of the tour. The slideshow is embedded below.)

First, let’s set the scene. The current station at South Ferry is more than a bit decrepit. It’s a tiny station with room for five cars, and since it’s on a steep curve, it employs movable platforms. Somehow, it also serves six million passengers a year bound for Staten Island, Lady Liberty and all points in between. When the federal government offered up a large grant to redevelopment Lower Manhattan, the South Ferry stop along with the tortured Fulton St. hub were chosen for funding.

First, let’s set the scene. The current station at South Ferry is more than a bit decrepit. It’s a tiny station with room for five cars, and since it’s on a steep curve, it employs movable platforms. Somehow, it also serves six million passengers a year bound for Staten Island, Lady Liberty and all points in between. When the federal government offered up a large grant to redevelopment Lower Manhattan, the South Ferry stop along with the tortured Fulton St. hub were chosen for funding.

The new station, when it opens next month, will carry with it a $527 million price tag, including $420 million from the feds, approximately $107 from the MTA’s coffers and the remainder from the city for the plaza that will one day surround the entrance.

So what can you get for $527 million these days? Well, for starters, we get 1800 feet of total construction. Of that, 1200 of those feet are a part of a brand new tunnel with the remainder serving as the station.

Instead of just one track, we now have two ten-car tracks. The station will serve as a bona fide terminal. As such, according to the MTA, the potential capacity along the 1 line will increase from around 17 trains an hour to up to 24, and the easing of the Lower Manhattan bottleneck could shave six minutes off of a trip from 242nd St. to South Ferry. The station is also equipped with signals ready for computer-based train control, if and when the MTA gets that program off the drawing board and into the tunnels.

But beyond the technicalities of the track, the station itself is chock full of modern amenities. It features various escalators including some of those new smart escalators that slow down and speed up as passenger demand increases. The platform itself is very wide. While my pictures don’t quite capture how wide they are, this double-sided staircase leads down to the tracks with room on both sides.

More impressive is the cooling technology in place. The new South Ferry terminal features tempered air. As best as I can tell, the system is an underground air conditioned that kept the station positively balmy on a cold December day and will, according to Horodniceanu, ensure that the station “won’t be as hot in the summer” as some of the others. Air conditioned subways! Who knew?

The mezzanine level is by far the nicest in the station. While it does feature the ubiquitious security cameras, it is an expansive and gleaming entry way to the station. Most noticeable is the artwork. The MTA Arts for Transit program spent $1 million on station decorations, and according to Sandra Bloodworth, the director of Arts for Transit, did so to tie the station into its surroundings. “The idea,” she said, “was to bring the park into the station.”

Past the turnstiles, the station features glass panels depicting trees, and outside, the security gates are beautifully designed to evoke the park instead of the MTA’s usually jail-like appearance.

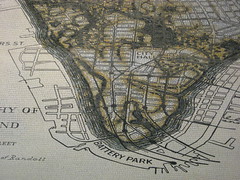

The jewel of the station is a mosaic map of Manhattan. Designed by the Starn Twins, the map is a 20-foot wide view of Manhattan from the Battery north. The first layer is a topographic map from 1640 and overlaid on that is a modern view of the city complete with the subway system. I snapped a detail of the map’s depiction of Lower Mahattan, and you can read more about the Starn brothers’ vision for the station at their website.

The jewel of the station is a mosaic map of Manhattan. Designed by the Starn Twins, the map is a 20-foot wide view of Manhattan from the Battery north. The first layer is a topographic map from 1640 and overlaid on that is a modern view of the city complete with the subway system. I snapped a detail of the map’s depiction of Lower Mahattan, and you can read more about the Starn brothers’ vision for the station at their website.

Beyond that, the station also features the 350-year-old Battery wall that held up construction when workers came across it a few years ago. When completed, it will connect to the BMT at Whitehall St. and feature a canopy entrance evocative of the DC Metro. Sadly, I doubt that the turnstiles will remain without arms for much longer.

The station looks great, and while it looked very much like a work in progress, Horodniceanu says it will open in January. Considering the engineering work that went into it — the station is built underneath the current South Ferry loop and the East Side IRT’s Joralemon St. Tunnel — it will stand as an impressive accomplishment in the painfully slow redevelopment of Lower Manhattan.

Shocking delays, cost increases rock South Brooklyn project

Who would believe that this project won’t wrap up on time? (Source: flickr user Betty Blade)

When the MTA announced earlier this week that the long-anticipated Culver Viaduct rehabilitation project would take longer and cost more than originally anticipated, Brooklynites the world over were shocked — shocked, I tell you! — by the news.

No, wait. They weren’t.

According to The Brooklyn Paper, this project and our dreams for an F Express train will have to wait longer than we had hoped. The MTA, according to the paper, still plans to begin the project next year, but the completion date for the station renovation at Smith and 9th Sts. has been pushed back to 2011.

Worse still for the cash-strapped agency is the price tag. Originally set at $187.8 million, the rehabilitation plan will now cost “upwards of a quarter-billion dollars,” as MTA spokesperson Deirdre Parker told Mike McLaughlin.

So that’s the bad news, and while I’m poking fun at the MTA’s inability to finish most major rehabilitation projects on time and at budget, there’s more at work here than simply business as usual. While The Brooklyn Paper story doesn’t get into the why’s of this delay and significant cost increase, we are well versed in these problems.

First, as with any other contractor in the city, costs are spiking. The economy is suffering through its worst downturn since the Great Depression, and with financial institutes collapsing and consolidating, a lot of construction projects are left unfunded and unfinished. The MTA, as a public benefit corporation, isn’t in danger of collapsing, but it will face rising costs. This 33 percent increase probably won’t be the last that we’ll see in regards to this project.

Second, the MTA itself has no money. The agency is attempting to reorganize internally and coax more money out of the state legislature. As such, it has to scale back their aggressive timetables for many of its top-priority projects. This is, of course, a double-edged sword. The longer these projects are delayed, the more they will cost. If the government were to provide for proper funding, the MTA would be able to improve its cost and timetable efficiency.

I know it’s rather naïve of me to think that a third Bloomberg term would deliver more respect to the MTA. But if we’re truly heading down that path, I hope the Transit Authority is allotted more financial resources over the next few years. If its not, we’ll be paying the price long past the completion of one long-delayed project in South Brooklyn.

The MTA’s South Ferry Christmas present

According to the Downtown Express, the MTA will open the South Ferry station this December just prior to Christmas. While the neighborhood weekly reports this as, more or less, an on time opening, in reality, this project was originally set for an early 2008 completion date. No matter the final deadline, this new two-track, full-train solution to South Ferry should make for an easier ride up and down the 1.

A State of Disrepair

Dov Hikind, a Brooklyn-based assemblyman, and Scott Stringer, the Manhattan borough president, both have fielded their fair share of constituent complaints about the state of the subway infrastructure. So they took matters into their own hands and examined 100 subway stations throughout the city. According to a report the two plan to release later today, they have found a system rife with structural problems and an MTA slow to respond to complaints. These findings are nothing new, but they are just another salvo for critics skeptical of the MTA’s ability to run the city’s transit network.

Ravitch charged with solving debt problems he helped create

Thirty years ago, when the ten-year-old MTA was facing a subway crisis, New York turned to Richard Ravitch to step in and save a decaying and unsafe system. Now, the 40-year-old MTA, suffering from the same economy slump affecting Americans the country over, has once again turned to Richard Ravitch to revive and revitalize the MTA’s finances. Ironically, Ravitch and his panel are tasked with solving a problem created by Ravitch thirty years ago: crushing debt brought about by investment in the subway system.

Thirty years ago, when the ten-year-old MTA was facing a subway crisis, New York turned to Richard Ravitch to step in and save a decaying and unsafe system. Now, the 40-year-old MTA, suffering from the same economy slump affecting Americans the country over, has once again turned to Richard Ravitch to revive and revitalize the MTA’s finances. Ironically, Ravitch and his panel are tasked with solving a problem created by Ravitch thirty years ago: crushing debt brought about by investment in the subway system.

This is quite the conundrum. Why would the MTA turn to Ravitch to fix a problem that stems, by and large, from policies he instituted and paths he chose in the 1980s? Better yet, how exactly did Ravitch create those problems? A very well done Ray Rivera article in The Times this weekend delved into the issue of MTA debt, and in Rivera’s work, we see the origins of the MTA’s current financial difficulties.

Rivera writes:

When Richard Ravitch was named chairman of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority in 1979, he inherited a subway system in decay. Trains derailed or collided on average every 15 days. Stations were filthy and crime was rampant. Ridership sank to lows not seen since World War I.

To revive the system, Mr. Ravitch, a former construction executive, persuaded lawmakers to allow the authority to do what countless cities and states had long done to build and maintain their infrastructure: Issue bonds.

“The system was falling apart, and the only way I could get the money to rebuild it was to borrow it,” Mr. Ravitch said in a recent interview.

Nearly 30 years later, the system is by all accounts better. But the authority’s debt has ballooned, and like stressed homeowners across the country, the system is groaning under the pressure to repay it. Indeed, debt payments are the system’s largest single cost after payroll, and by 2012 they will account for one of every five dollars the authority spends.

Rivera goes on to talk about the recent restructuring of the MTA’s finances. The agency is on the hook for debt payments until, at the earliest, 2032, and those payments amount to at least $1 billion annually. If the agency wants to expand its system, as it is doing now, if the MTA wants to keep stations in a good state of good repair, renovate those that need improvements and keep equipment modern, those debt tolls could increase.

And it all started with Ravitch:

Money for capital improvements hovered around $50 million — not the billions Mr. Ravitch and his analysts knew it would take. So he went to Albany.

“The Legislature squawked,” recalled Mr. Ravitch, 75. “They said that will result in a fare increase, and I said ‘That’s absolutely correct.’ But I said it will also result in an improvement in the system and attract more riders and avoid the dysfunctionality in the system, and they were persuaded.”

The law passed in 1981, and the next year the authority issued its first bonds, totaling $350 million. The authority issued hundreds of millions of dollars in new debt over the next 20 years, nearly all of it going toward new stainless steel cars and buses, and track repairs, signal replacements and other system improvements. By 2000, the agency’s outstanding debt had reached $12 billion.

Over this time period, as the MTA fell further and further into debt, city and state politicians were content to let the transit authority crumble. Until 1991, New York City and State funded a combined 26 percent of the capital plans. From 1992 onward, that contribution fell to a meager nine percent, and the MTA had to rely on the money they could raise from bond sales. Right now, if all of the MTA’s bonds were recalled, the transit agency would, in all likelihood, default.

This time around, Ravitch is going to have to rely on something other than yet another bond issue to fund the MTA. The transportation agency cannot continue to borrow against itself to fund capital improvements, system expansions and maintenance programs. Ravitch will have to demand more money from a government strapped for cash, and identify some other sources of dedicated revenue stream. As we know, Ravitch got us into this mess by suggesting bond issues in the first place. Can he get us out of it?

An entrance opens amidst the Columbus Circle mess

In April, an imposing blue wall pointed the way into the Columbus Circle station. (Photo by Benjamin Kabak)

The Columbus Circle station is, in a word, a mess right now. Undergoing a massive renovation, the station is dirty, hot, dusty and impossible to navigate. While this should be the state of things at 59th St. for at least the better part of the next year, the MTA celebrated a milestone in the construction yesterday when a new entrance opened at 60th St. and Broadway.

For the celebration, the MTA broke out the ribbon-cutting scissors, and MTA CEO Executive Director Lee Sander did the honors. As this entrance opens, the one on the island in the middle of Broadway closes, and the MTA tells us more about this new entrance and the final plans — with their 42-month timeline and $108-million price tag — for the station:

The new 60th Street control area cost $14 million and was carved out of solid rock made up of the well-known Manhattan schist while a vast array of street utilities were suspended from the decking beams. Those utilities included 20-inch and 32-inch city water lines, a 20-inch Con Ed steam line as well as numerous smaller electric, gas and fiber optic lines. The entrance, which includes two new street-to-platform level staircases and a MetroCard Vending Machine, was newly constructed under concrete decking, which minimized the disruption to street traffic on southbound Broadway.

“Funding for transportation is a scarce commodity, but we are doing everything we can with the resources we have available to improve the experience our customers have with us,” said Elliot G. Sander, the Executive Director and CEO of the MTA. “Whether it is a much needed new subway entrance or the initiation of Select Bus Service, we are committed to improving customer service.”

“This station rehabilitation project and particularly this new entrance are examples of the difficulties NYC Transit faces when upgrading what is an aging system,” said NYC Transit President Howard H. Roberts, Jr. “Despite the complexities of the construction, we have delivered to the customers who use this station a new, modern entrance which will provide additional egress capacity for the more than 69-thousand people who use the station daily.”

In the end, the renovated station will feature an elevator at one of the Central Park West access points and three new staircases along Broadway. Both platforms levels will be overhauled, and the now-abandoned central platform on the A/B/C/D level will be restored to use.

For many, the current state of the station is a major inconvenience. It’s not a pleasure to navigate through Columbus Circle right now. But in the end, it should be worth it. With the Time Warner Center and CNN occupying what had been largely unused real estate at Columbus Circle, this popular station has become more overrun with people, and the MTA, beleaguered and beaten, is doing all it can to modernize this station. Now if only they could do something about the other 467 at the same time.

Hiring delays slow MTA’s big-ticket items

Over five months ago — an eternity in the world of construction — Mysore Nagaraja left his post as head of MTA Capital Construction. Since then, the MTA has soldiered on with an interim head in place; Veronique Hakim is still just the acting head of the construction agency.

Over five months ago — an eternity in the world of construction — Mysore Nagaraja left his post as head of MTA Capital Construction. Since then, the MTA has soldiered on with an interim head in place; Veronique Hakim is still just the acting head of the construction agency.

Now, however, this turmoil at the top has the feds worrying that the MTA is falling behind on their big-ticket items such as the Second Ave. Subway and the LIRR East Side Access project. The news just keeps getting worse for the MTA, and the future for a few much-needed expansion plans remains murky.

Pete Donohue had more about the feds’ concerns:

The Federal Transit Administration is concerned that major MTA construction projects could be mucked up because the authority hasn’t filled high-level management positions, the Daily News has learned.

“Several key positions,” including Capital Construction president, “continue to be filled on a temporary basis and other key positions are still vacant,” FTA monitors wrote in an April report in a section titled Major Issues/Problems.

Later in the report, which focuses on the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s extension of the Long Island Rail Road to Grand Central Terminal, the feds observe that an MTA-hired consultant “continues to stress the importance for [the MTA] to fill these positions as soon as possible to properly manage a project of this magnitude.”

The Daily News also notes that the project’s completion date is now 2015, two years late, and that the plan is now $1 billion over budget. Somehow, that’s less surprising than it should be.

For their part, the MTA says a new Capital Construction head will be forthcoming, and that person couldn’t arrive soon enough. With their finances in turmoil, the MTA can’t allow their on-going and federally-supported construction projects to fall further behind. The agency needs the continued support of the feds, and New Yorkers need these expansion plans to become a reality.

4th Ave. F station rehab to get budget axe

This rendering will forever remain a very nice picture.

It’s starting, and I hope it doesn’t end up costing the city the Second Ave. subway yet again.

In a move that isn’t too shocking, the MTA has abandoned its plans to do a full overhaul of the 4th Ave. station on the F line. While the agency will still rehab all of the tracks and Culver Viaduct structure itself, in an effort to save nearly $65 million, the MTA has withdrawn the station rehab plans. This move is a big blow to an area sorely in need of an aesthetically appealing station and is sure to be an early warning sign of more construction cuts to come.

Mike McLaughlin of The Brooklyn Paper broke the news late last week:

The almighty transportation agency has abandoned its ambitious plans to renovate the shabby Fourth Avenue station in Park Slope into a glittering, light-filled, Euro-styled stunner.

Just last November, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority showed off renderings (left) of the elevated F-train platform basking in sunlight from new windows, renovations that were part of a larger project to reconstruct the crumbling elevated tracks on the F and G line between the Carroll Street and Fourth Avenue.

The trackwork is still set to start later this year and finish in 2012. And improvements to the equally beleaguered Smith–Ninth Street station are still slated to begin next year. But the overall $250-million project has been trimmed to $187.8 million, so something had to give, said Deirdre Parker, a spokeswoman for New York City Transit.

“Work on the Fourth Avenue station was never officially funded. Consideration has been deferred until the next capital plan,” Parker said in an e-mail to The Brooklyn Paper. And, yes, that next capital plan will roll around in, oh, 2013.

While the Smith-9th Sts. station will get its much-needed aesthetic overhaul, this news is just another step backwards for an MTA that has spent much of 2008 backtracking on promised upgrades. It’s easy to renege on promises of aesthetic upgrades; they don’t impact train performance. But as many transit rider advocates note in McLaughlin’s article, appearances matter. (Ed Note: See clarification at bottom.)

Meanwhile, I can’t help but fear for the future of other big-ticket items. A whole bunch of Q stops are set for renovation, and various projects — Chambers St. on the BMT Nassaue Line, South Ferry, Bowling Green, to name a few — are in different stages right now. Could these all face the axe as the MTA looks to trim its budget? Are we looking an age in which station aesthetics – already a sore point for the MTA — are sacrificed even further in the name of money?

And then what happens when we start looking at the big-ticket capital projects? Are the Second Ave. Subway and LIRR East Side Access projects in danger?

In the various questions posted to Gene Russianoff on The Times’ City Room blog, more than a few straphangers focused on station aesthetics. As anyone who’s been to London or Paris or Moscow can attest to, New York’s subways are a visual mess, and I fear that, as the pursestrings tighten, this is a situation that will not improve any time soon.

Addendum: Paul Fleuranges, NYC Transit’s Vice President, Corporate Communications, writes in with a clarification and a correction this morning. “There was never any intent to perform a full station rehabilitation of the 4th Avenue station during the Culver Viaduct rehabilitation; as such work is not contained in the funding envelope for this particular capital improvement in the 2005 – 2009 program,” he says.

Instead, the work will include surface reconstruction in a station that has seen parts of its outdoor platform beginning to crumble. The 4th Ave. renderings were simply views of what the station could look like if it were to receive funding in the capital plan that covers 2010-2014.

Are the MTA’s capital plans hanging in the balance?

Three days ago, the MTA dropped the news that a second fare hike may become a reality in 2009. Lost in the news on Friday were some alarming reports about the state of the MTA’s capital plan.

Three days ago, the MTA dropped the news that a second fare hike may become a reality in 2009. Lost in the news on Friday were some alarming reports about the state of the MTA’s capital plan.

In discussing the financial state of the transportation authority, Mayor Bloomberg dropped a bit of a bombshell about the MTA’s construction plans. Pete Donohue repoted on Mayor Mike’s statement:

Mayor Bloomberg warned Friday that straphangers could face another fare hike next year – and said the city is broke and can’t help.

The mayor also said the MTA’s construction plan is in “shambles,” and he slammed state lawmakers for sinking his congestion pricing plan – which would have raised transit money.

“I think there is a very good likelihood that we are going to have to face the issue of a fare increase or something else,” Bloomberg said on his weekly radio show. “The city doesn’t have any money to give. We are out of money.”

We know about the fare hike, but we hadn’t heard about the problems facing the MTA’s construction plans. For a while, rumors have swirled about the state of the progress on the MTA’s big-ticket items. Observers have noted a lack of above-ground work on the Second Ave. subway and the LIRR’s East Side Access project. Now, Bloomberg’s statement confirms our worst fears: The MTA could be facing a construction problem.

Across the city, the spiking cost of work is effective progress on buildings and development. Concrete costs are up; raw material prices have gone through the roof; and the MTA is not immune to these increases. A few weeks ago, the MTA noted that real estate revenues were down by nearly $81 million off of projected levels.

The MTA has long said that these problems won’t impact construction and expansion plans, but something has to give. Either we’re facing a fare hike or the MTA is facing a massive economic problem that could bring reduced service and a construction shut down. While these problems are not unique to New York, we can’t really afford to see the MTA fall into a recession reminiscent of the 1970s.

We’ll either see yet another fare hike or the government — the city, the state, the feds — will have to come through with the bucks. Either way, this tale is far from over.