The new fares shown in the table here go into effect on March 19, 2017.

At the last board meeting of his almost four-year tenure atop the MTA, outgoing Chairman and CEO Tom Prendergast had the unfortunate opportunity to oversee yet another vote to approve a fare hike. For Prendergast, this was the agency’s second fare increase during his tenure, and he missed a third by a matter of days as Joe Lhota resigned from the MTA nearly moments after voting for the 2013 fare hike. These increases have become a way of life for New York, part of the MTA’s fiscally responsible plan to catch up with inflation by raising rates every two years, but this economic reality doesn’t make them any easier to swallow.

For the MTA, last week’s fare hike vote came wrapped in intrigue. The MTA had proposed a $3 base fare with a substantial 16 percent bonus for pay-per-ride card purchases above $6 which effectively made the fare $2.59. But the public could not stomach a $3 per-swipe deduction, and the agency ultimately approved a deal worse for all but ocassional riders and those who cannot afford to buy fares in bulk. The per-swipe cost will still be $2.75, but the bulk discount bonus will drop to 5 percent for purchases of $5.50 and above. The actual cost of a ride, then, will be $2.62 or three cents more than it would have under the $3 proposal. It is perhaps a psychological victory for riders but not exactly an economic win.

For those who pay time-based passes, the increases were a fait accompli as both fare hike proposals included the same increases for unlimited ride cards. A 30-day card will now cost $121, up $4.50 for its current rate, and 7-day cards will see a $1 bump to $32. For those who ride at least 47 times a month and can afford an initial $121 outlay, the 30-day card is the best deal while the 7-day card requires 13 rides. Express bus fares jumped 50 cents, and Metro-North and LIRR riders will see increases of around four percent, all of which are tracked in this pdf.

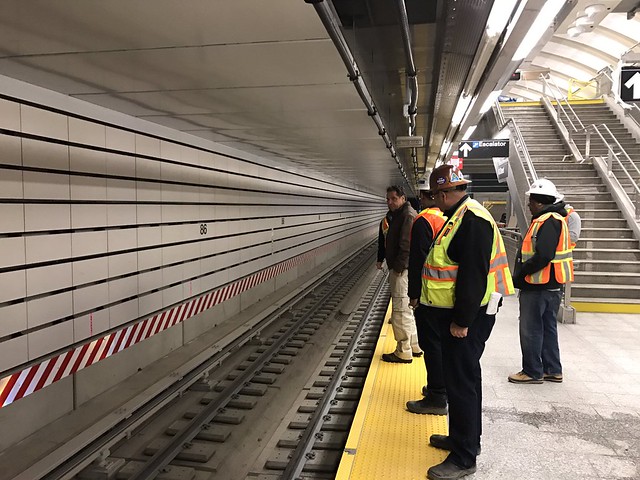

The new fares will go into effect on March 19, and I’ll have any details on grace periods for 30-day cards and other sunsetting windows as the MTA announces them. The agency, meanwhile, tried to spin this with good news as this year’s biennial increase is a lower-than-expected hike. “The MTA is focused on keeping our fares affordable for low-income riders and frequent riders, and on how we can keep necessary scheduled increases as small and as predictable as possible,” Prendergast said in a statement. “Keeping fares and tolls down was possible because of the continued operational efficiencies and ways we have reduced costs while adding service and capacity along our busiest corridors, most recently with the opening of the new Second Avenue subway.”

Yet, what was notable about the debate of the fare hike wasn’t really around the details of the MTA’s fifth fare hike since 2009 but rather what it didn’t include: any relief for low-income riders. For months, a coalition of activist groups has been pushing the city, state and MTA on implementing a subsidized fare program for low-income riders who are challenged to find the money for transit fares. Depending upon the income cut-off, such a program would likely cost around $174 million per year, in line with the total amount the MTA spends on subsidized student fares. Groups have targeted both the mayor and the governor, but in the grand tradition of the de Blasio-Cuomo feud, the mayor has pointed to the governor as responsible for transit funding decisions and the governor has done nothing. It’s possible to make a case that either the city or state should fund this initiative, and I’m not sure there’s a wrong answer. But right now, no one is funding this fair fare proposal.

And so our rides will get a little bit more expensive in March. It’s becoming the cost of doing business in an era without congestion pricing or cost controls.

It’s been a few days, and the news hasn’t stopped on the transit front. As the MTA Board prepares to vote for a fare hike on Wednesday —

It’s been a few days, and the news hasn’t stopped on the transit front. As the MTA Board prepares to vote for a fare hike on Wednesday —