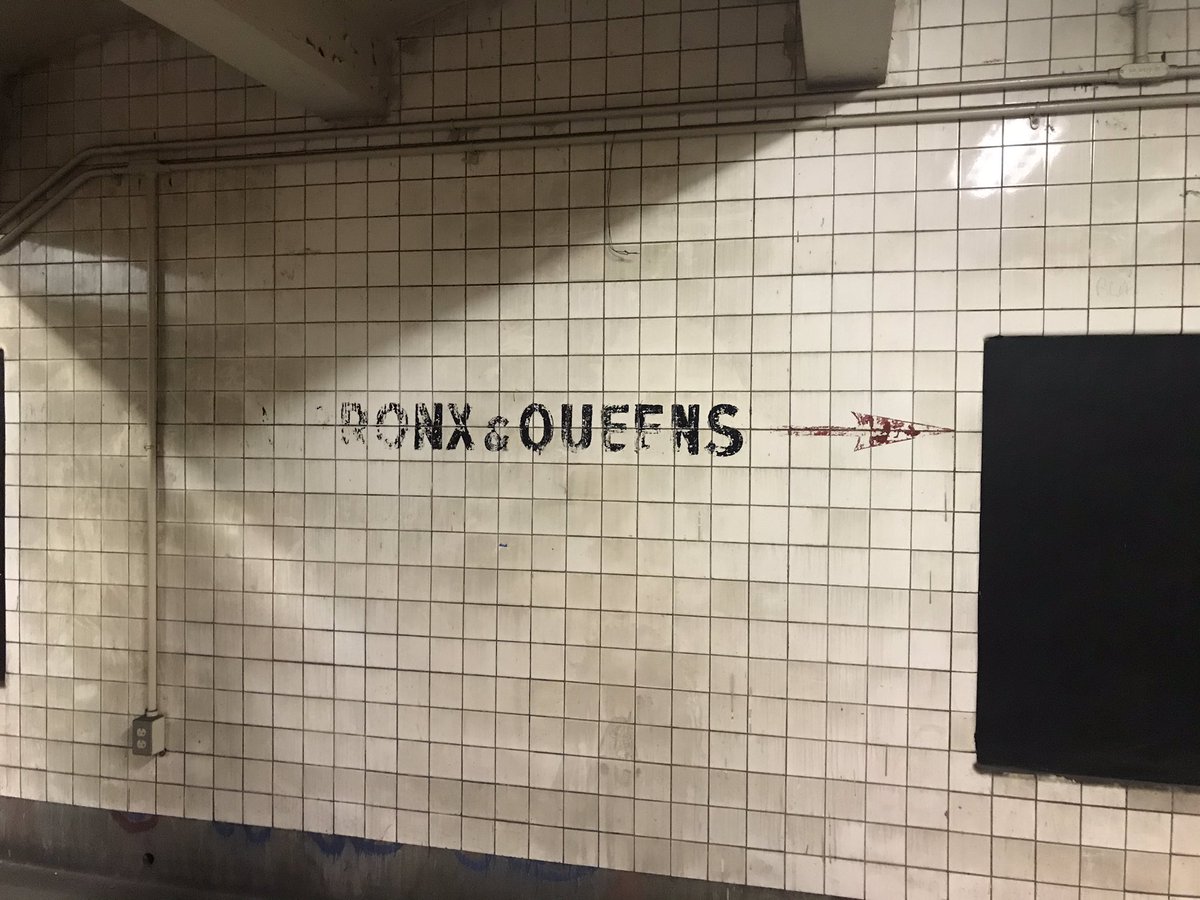

This vast mezzanine, a hallmark of the IND stations, will reopen as part of the work to restore entrances to the Nostrand Ave. A/C train at Bedford Ave. (Photo via Dan Rivoli on Twitter)

After years of requests from neighborhood activists and transit advocates alike, the MTA will finally reopen a pair of shuttered Bedford Ave. entrances to the Nostrand Ave. express stop along the A and C lines, the agency and a pair of local politicians announced on Thursday. The move reverses a late-1980s or early-1990s decision to close a giant mezzanine and staircase to Bedford Ave. and will help provide a shorter connection to the B44-SBS and better disperse passengers at the 77th busiest subway stop in the city.

For riders who live west of Nostrand Ave., reopening the entrances at Fulton St. and Bedford Ave. is a huge boon. The long-closed staircases are approximately 1000 feet away from the station’s remaining entrance and could shorten commute times by as much as four minutes each way. The work to reopen this entrance and a massive IND mezzanine will also restore a long-lost free in-station transfer between Nostrand’s northbound and southbound platforms.

The work involves rebuilding street-level staircases and station entrances, which were decked over as emergency exits decades ago, cleaning up corridors and staircases that haven’t seen passengers in over twenty years, and installing turnstiles and other elements of a modern fare control area. The MTA expects to reopen the entrances by the end of the year at a cost of approximately $2 million, $500,000 of which is being provided by Assembly Member Tremaine Wright and $250,000 of which comes from retiring State Senator Velmanette Montgomery. The MTA will pony up the rest as an operating expense.

“I am delighted to stand with the MTA, Senator Montgomery and our community partners to announce the much-anticipated re-opening of the second exit at the Nostrand Avenue A/C train station,” Assembly Representative Tremaine S. Wright said in a statement. “Every day, more than 36,000 people pass through this station and the re-opening of this passage way will alleviate much of the congestion. We are certain that this will improve the daily experience of subway users as well as enhance safety.”

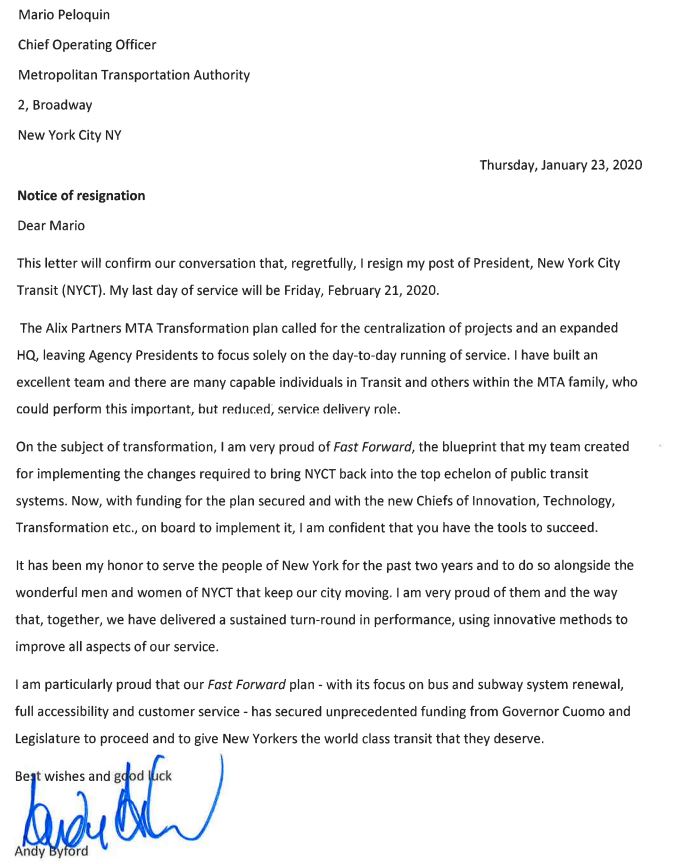

Stenciled signage in areas of the station closed for decades recall a time when the C train provided service along the Concourse Line in the Bronx. (Photo via Dave Colon on Twitter)

In announcing the reopening, the MTA noted that these entrances were closed 30 years ago “during a period of concerns about crime,” and it’s certainly a testament to the safety of the system today that the agency has embarked on an effort to reopen numerous closed entrances around the city. It’s a topic I first explored in a post nearly a decade ago that highlighted the walkway connecting 7th and 8th Aves. underneath 14th St. and the Gimbels Passageway. Internally, the MTA had identified the Bedford Ave. entrances as prime candidates for reopening in a 2015 line review of the A/C trains [pdf]. Better five years later than never, I guess.

That said, the Bedford Ave. entrances at Nostrand have a tortured history. Although the IND Fulton St. Line originally opened in 1936, the entrances at Bedford will kept sealed until 1950 when the Bedford-Stuyvesant Neighborhood Council finally convinced the Board of Transportation to install turnstiles and open the exits. It’s not quite clear when the entrances were closed as the MTA’s own release puts the date around the 1980s, and available public newspaper articles suggests that the uptown/downtown crossover was shuttered in 1991 in the aftermath of a headline-grabbing rape in a deserted passageway connecting Herald Square to Bryant Park. In essence, then, since the IND’s Brooklyn debut in the mid-1930s, the Bedford Ave. entrances have likely been closed for longer than they’ve been opened.

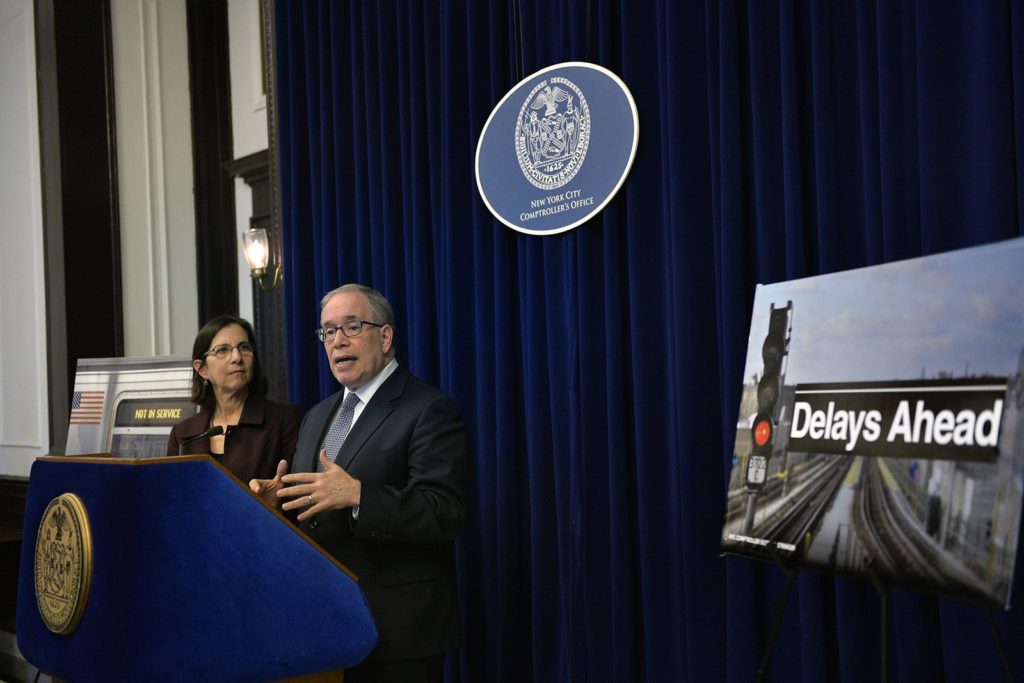

Recently, the MTA has opened a number of old entrances, largely in conjunction with work on the L train, but they still have many more to go as attention has slowly shifted to these elements of the built environment that have been unused for most of the past three decades, if not longer. One Wikipedia contributor has built what many consider to be the master list of closed entrances, and recently, NYC Comptroller and a likely 2021 mayoral hopefully Scott Stringer penned a letter to the MTA asking for information about closed entrances. Stringer noted that as of a few years ago, the MTA had identified 298 staircases closed to the public at 119 different stations and requested the agency develop a five-year roadmap for opening these staircases.

“Millions of New Yorkers rely on the subway system every day to commute to work, attend classes, go to job interviews, see a doctor, and take their children to day care. At a time when system failures and overcrowding are already crippling commutes, especially for low-income New Yorkers, the abundance of shuttered subway station entrances across the five boroughs is problematic and unacceptable,” he said in his letter. “This is not just about reducing commute times, it’s about equity and fairness. We need a roadmap to improve mobility and accessibility for transit riders throughout the five boroughs.”

As the Bedford Ave. entrances ready for their reopening, I’m reminded of a story I once told regarding the opening of the giant mezzanine during the 7 line extension ribbon-cutting. I overheard an MTA official marvel at the open space as they said “I’ve spent my entire career closing these mezzanines.” For years, the MTA has hidden behind trumped-up concerns about safety to close off vast public spaces that make transit easier to reach and then relied on the argument that the ADA required them to include full accessibility upgrades if they were to reopen station entrances. As Nostrand Ave. is due for those upgrades as part of the 2020-2024 capital plan, the MTA feels that promise is sufficient to overcome legal challenges to reopening the entrance prior to (rather than concurrent with) any ADA work, and the entrances, it seems, are finally coming back to life.

As far as maximizing transit capacity and improving operations, reopening closed entrances is low-hanging fruit that can pay big dividends. For a minimal one-time spend, the agency has made an express station far more convenient for thousands, and by opening up the western end of the Nostrand Ave. station to passengers, the move should better disperse crowds along the platform, improving dwell times and crowd control. With an entrance to the express train now significantly closer for many, the move should also ease some crowding along the C train, and the 6-8 minutes in reduced walking time per passenger each day will add up quickly. This move makes transit more accessible and easier to reach for thousands and should be replicated as fast and as frequently as possible throughout the city.

As 2019 draws to end, I wanted to release one more podcast episode, and this week, you get to spend a half an hour with me and

As 2019 draws to end, I wanted to release one more podcast episode, and this week, you get to spend a half an hour with me and