This sign will become a collector’s item as the overnight subway shutdown will end on May 17, Gov. Cuomo announced Monday. (Photo by Benjamin Kabak)

Just over a year to the date since Gov. Andrew Cuomo barred passengers from late-night subways, the man in charge of the MTA announced the return of 24/7 subway service. The trains, which kept running all night every night for the last year, will see the return of passengers between 2 a.m. and 4 a.m. on May 17th when outdoor dining curfews and pandemic-related capacity limits wind down. It’s welcome news for essential workers who saw their late-night commute times spike and costs increase while they just tried to keep NYC running throughout a pandemic, and it’s a sign that life may be returning to normal sooner rather than later.

For many transit advocates and enthusiasts, the news comes with a great sigh of relief as worry had spread that the governor would use the pandemic shutdown to end 24/7 subway service once and for all. After all, the governor had signaled for years through his MTA Board loyalists that 24/7 passenger service was a luxury for New York rather than the necessity we know it is, and MTA officials had once said the subways were “going to stay closed overnight…at least through the pandemic.”

But once the governor rolled back the four-hour shutdown to two a few weeks ago, we knew logistics and political pressure would eventually win out. The MTA simply cannot park all of its trains securely and kept running empty subways each night throughout the pandemic. Once Senator Chuck Schumer joined the fray, calling this weekend for the return of 24/7 service, it was all but inevitable that Cuomo would cave.

In announcing the restoration of service, Cuomo again trumped the disinfecting regime and baselessly hinted that the subways were responsible for the spread of COVID, his long-time cover for a policy driven by media coverage of homeless New Yorkers sprawled across subway seats and a safety crisis during the worst few weeks of the initial wave of the pandemic.

“COVID-19 is on the decline in New York City and across New York State, and as we shift our focus to rebuilding our economy, helping businesses and putting people back to work, it’s time to bring the subway back to full capacity,” the governor said, taking responsibility for the MTA he controls. “We reduced subway service more than a year ago to disinfect our trains and combat the rising tide of COVID cases, and we’re going to restore 24-hour service as New York gets back on the right track. This expansion will help working people, businesses and families get back to normal as the city reopens and reimagines itself for a new future.”

Despite a heavy security presence, the governor claimed Monday that he felt on safe during his last subway ride on June 8, 2020. (Photo via governorandrewcuomo on flickr)

Yet, the governor also went off script in some head-scratching ways. The governor, who has not ridden the subway since June 8 when he took a 7 train four stops from Court Square to Grand Central, claimed he felt physically unsafe on the subway (despite being surrounded by numerous cops and adoring fans). “As you know, I am a New Yorker. I am smart. I am New York tough. Don’t lie to me and don’t play me as a fool. I’m on the subway. It’s safe. Oh, really? Have you been on the subway? Because I have. And I was scared. Tell your child to ride subway, it’s safe. I’m not telling my child to ride the subway, because I’m afraid for my child,” Cuomo said.

I’ll get into the ins and outs of the ongoing conversation about safety in the subway in an upcoming post, but it’s all part of his feud with the mayor. The numbers show major felonies in the trains are up only slightly but transit workers are getting assaulted at alarming rates and misdemeanors and harassment over goes under- or unreported. MTA officials and Cuomo aides have talked up concerns about subway security while city cops have stressed the massive decrease in crime since last April and the relative safety of the system. The governor, who controls the MTA, should not be adding to the fearmongering, especially as he trumpets New York’s reopening and a return of passengers to overnight subways.

But the governor couldn’t resist plying the subway shutdown as another part of his infamous feuds with the mayor. Bill de Blasio had called for a resumption of normal life in New York City by July 1, but the governor has decided mid-May is the appropriate timeline. The mayor didn’t put up much of a fight on “Inside City Hall” on Monday night, suggesting that his July 1 date was as much a move to goad the governor into acting faster as it was a hard deadline driven by public health figures. But the fight over 24/7 service has its origins in the de Blasio-Cuomo battle as the mayor urged the MTA last April to close terminal stations for easier treatment (and removal) of homeless New Yorkers from the subway before the governor took a sledgehammer to the idea and ended overnight service from 1-5 a.m. entirely.

MTA officials have pledged to continue to clean trains overnight and support mental health services in the subway. Interim NYC Transit President Sarah Feinberg went on the radio yesterday evening and continued the theme. Riders, she said, “continue to worry about crime and harassment in the system because we’re not where we need to be on that yet and so until my customers and my workforce are saying, ‘We feel really good, we feel as safe as we could possibly feel,’ I’m going to continue to bang the drum on it ” This response is all part of the complicated politics MTA officials have been trying to maneuver lately, and I’m confident this won’t be the end of the various debates about homelessness in the subways, the reality and the perceptions of safety or the way the governor uses the MTA as a pawn in his political games against the mayor.

So did anyone learn anything during the 12 months without passenger service? We learned that a lot of New Yorkers were continually surprised to learn that the trains kept running but without anyone on them. We learned repeatedly that Bill de Blasio viewed overnight subway service as a luxury for party-goers and denizens of New York City’s late-night scene rather than as an essential means of travel for late-shift workers who often live far from the city’s job centers but kept New York going through its darkest days this past year. We learned that homelessness drives the conversation but not in ways that produce positive change (as subway bathrooms remain closed and Moynihan Station has no public seating). We learned that the city and state haven’t taken steps to address some of the root causes of why people choose to live in the subways or how to get them more secure housing. And we learned that while the MTA was able to accomplish some work on a slightly accelerated timescale, denying passenger service throughout the system as a whole does very little to increase construction productivity.

We should also learn for the sake of New York City’s future that the governor shouldn’t have the power to simply turn off the subways overnight with flimsy reasoning and no real way to cajole him to turn it back on for over a year, short of his losing influence due to the impact of duel scandals breaking as the vaccine effort ramped up. Yet, as life returns to normal, these lessons will fade, and the overnight subway shutdown will become one of those things we remember now and then about the COVID-19 pandemic that will recede into New York City history. It should be a cautionary tale about politicians who misunderstand the fundamental role transit plays in the city’s success. For now, though, in two weeks, the subway, in all its overnight glory, is back. It’s a welcome step forward indeed.

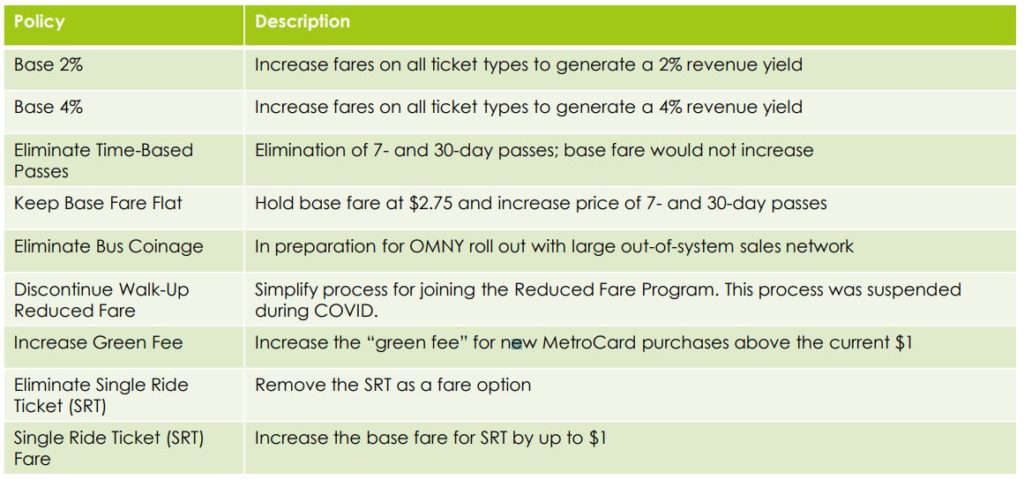

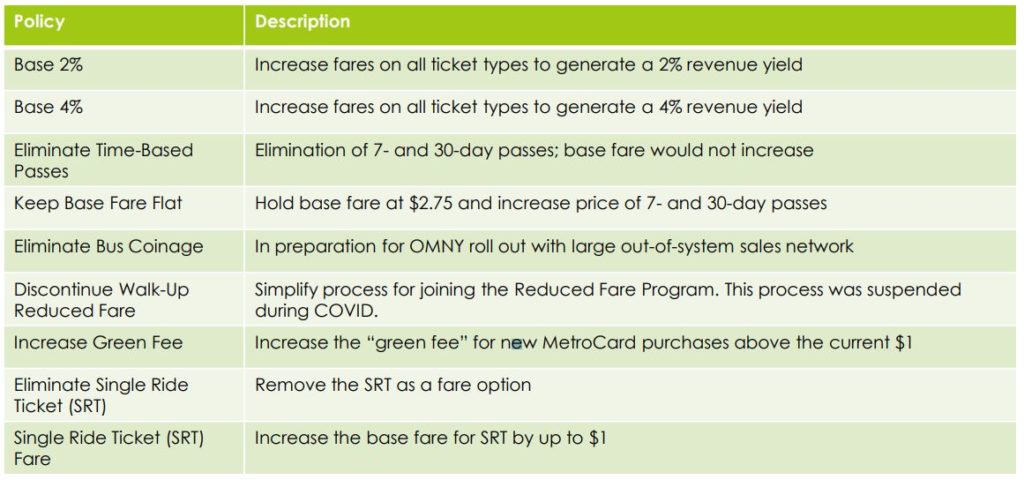

Amidst an ongoing pandemic that has decimated the economy and reduced daily transit ridership to essential workers traveling to keep the city and themselves afloat, the MTA Board has tabled talks of a fare hike, agency officials confirmed on Monday. The decision comes after months of public pressure by both elected officials and transit advocates, and it marks the first time since biennial fare hikes began in 2010 that the MTA Board — and by extension, the governor — has opted to cancel or at least postpone a fare hike.

Amidst an ongoing pandemic that has decimated the economy and reduced daily transit ridership to essential workers traveling to keep the city and themselves afloat, the MTA Board has tabled talks of a fare hike, agency officials confirmed on Monday. The decision comes after months of public pressure by both elected officials and transit advocates, and it marks the first time since biennial fare hikes began in 2010 that the MTA Board — and by extension, the governor — has opted to cancel or at least postpone a fare hike.