What happens to New York City without its transit system? Can the city function? Can it succeed? Can it serve as the self-professed Center of the Universe if the subways and buses that, in normal times, serve well over 7 million riders a day, can’t run frequently throughout the day? Can the Big Apple recover from the economic crisis of the pandemic without robust transit or will a transit decimated by political failures at every level drag down the city and the country as NYC and the USA, both hanging on by a thread right now, look to a post-COVID future? We may soon find out.

Facing billions of dollars in revenue shortfalls due to the ongoing pandemic, the MTA Board two weeks ago took another step toward enacting the agency’s Doomsday budget. With paralysis gripping the U.S. Senate and Mitch McConnell still refusing to negotiate a new stimulus package, the MTA’s financial picture has not improved since the Board first contemplated the worst-case scenario in August. Now, with the remainder of 2020 measured in days rather than months, the MTA has just a few weeks left to wait for federal relief before the Board is faced with the unenviable task of approving the budget presented at November’s meeting. It’s one that could cut service by up to 40 percent, but it remains a very political document aimed at Washington and with a glimpse at what the MTA truly needs to stay afloat through 2021.

During November’s Board meeting, the MTA did not vote on a 2021 budget; that procedural move will wait until December’s meeting, likely to be scheduled shortly before Christmas. Instead, the agency rehashed the same story it has been telling since the spring and again reissued its non-stop call for federal aid.

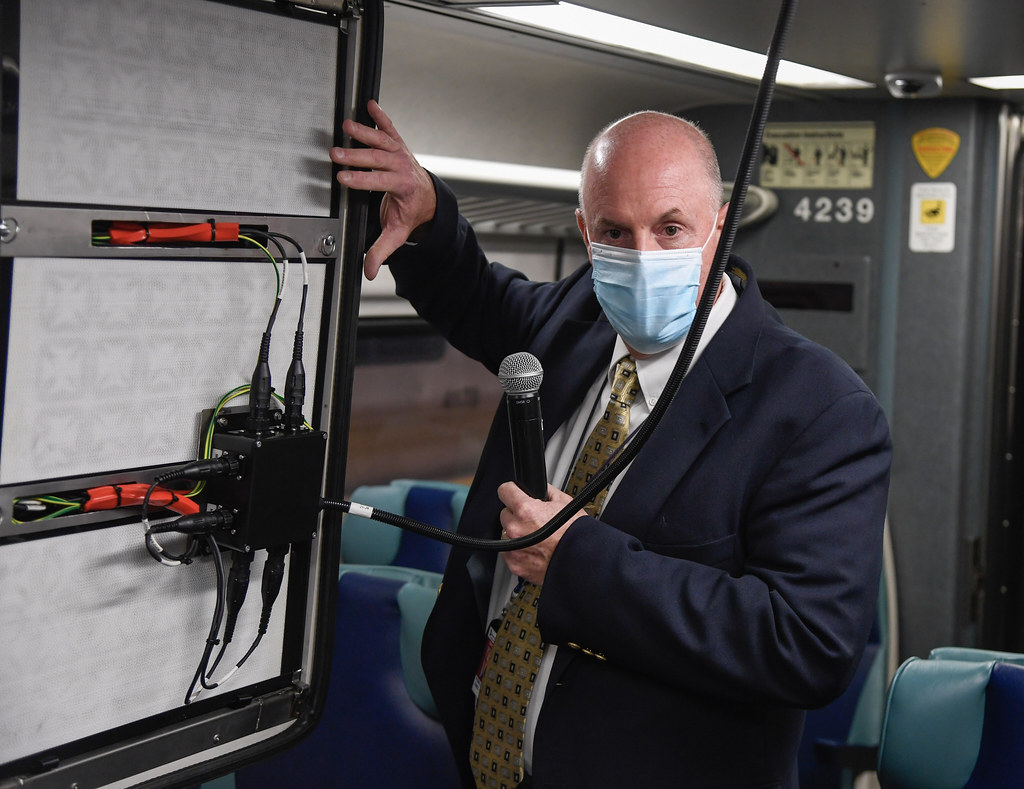

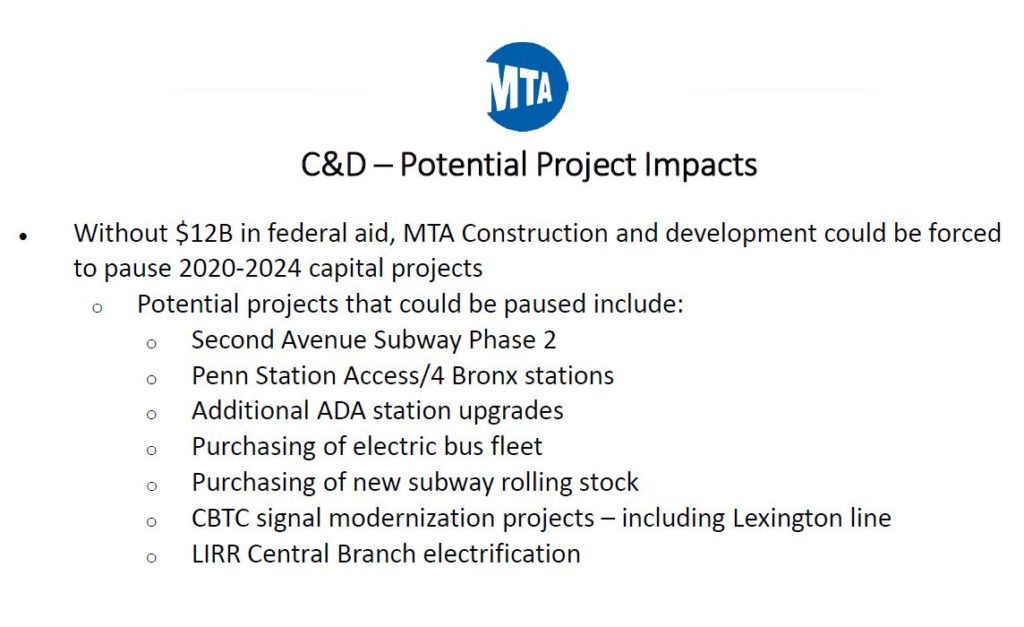

“The MTA continues to face a once-in-100-year fiscal tsunami and this is without a doubt one of the most difficult and devastating budgets in agency history,” MTA Chairman and CEO Patrick J. Foye said. “No one at the MTA wants to undertake these horrific cuts but with federal relief nowhere in sight there is no other option. As I have said, we cannot cut our way out of this crisis – we are facing a blow to our ridership greater than that experienced during the Great Depression. We are once again urging Washington to take immediate action and provide the full $12 billion to the MTA.”

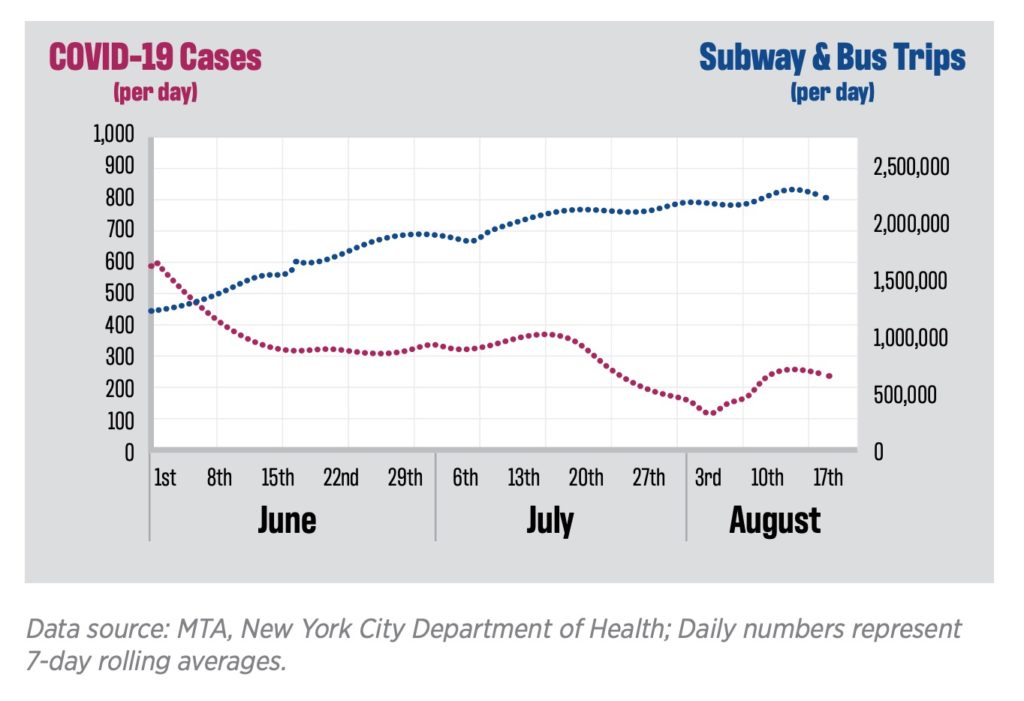

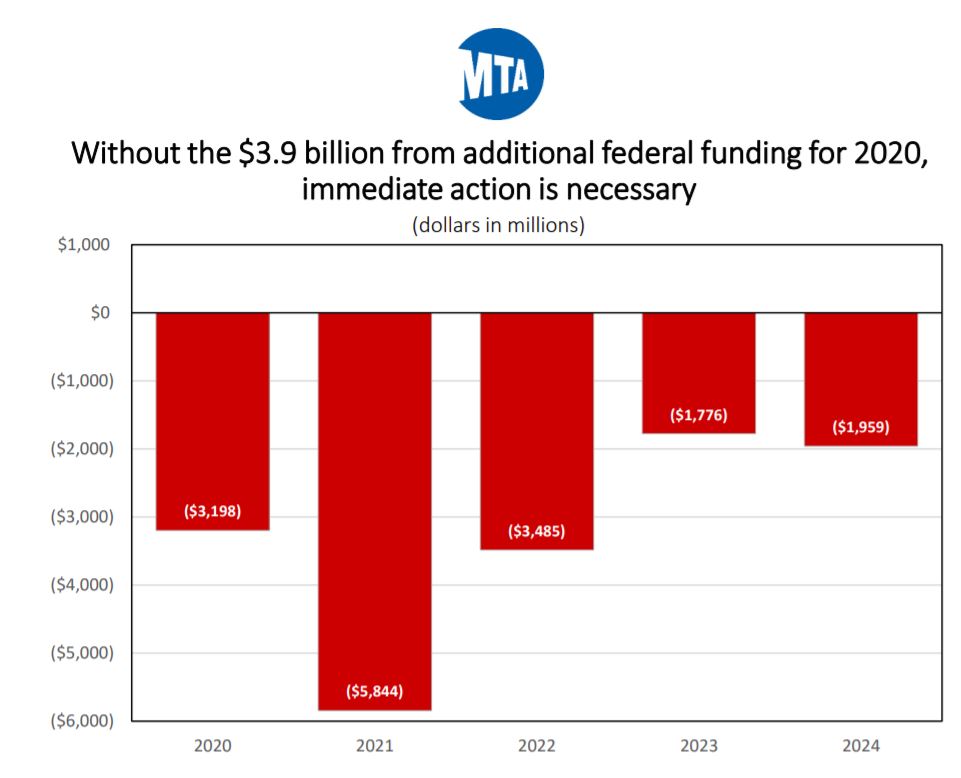

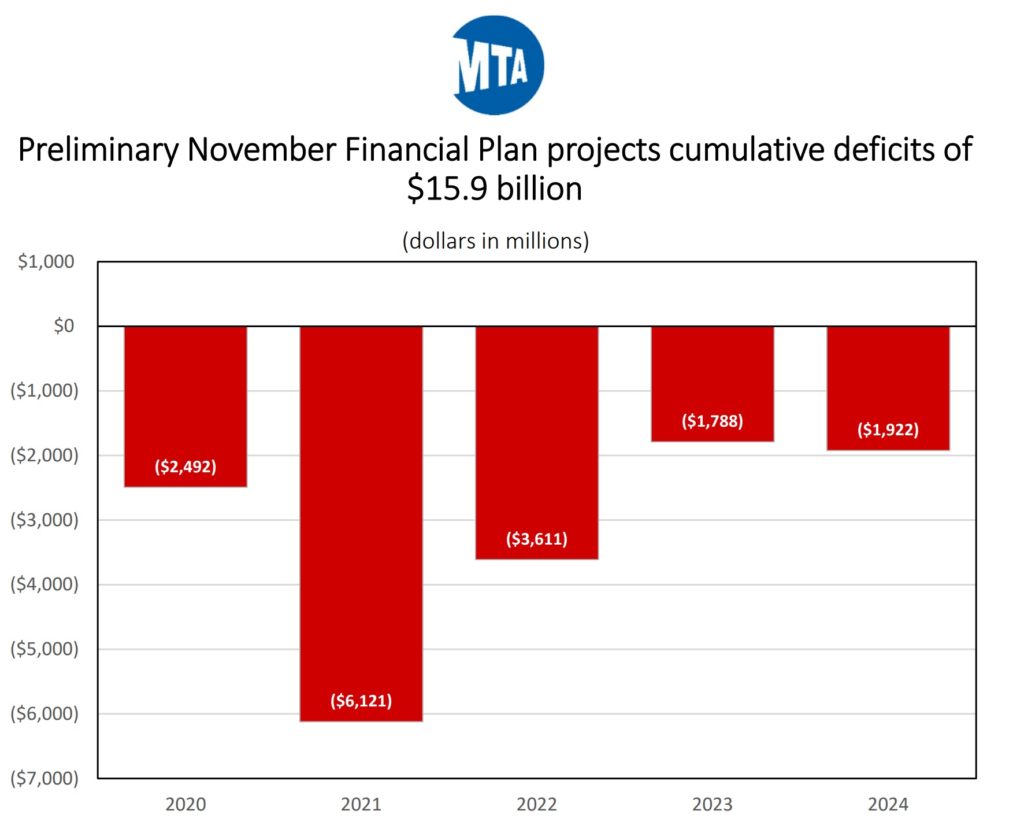

What we learned was this: Since the MTA’s July budget, its financial picture has worsened, largely due to federal inaction on a pandemic relief package. Ridership remains as expected — subway ridership is hovering at around 31-32 percent of normal while buses have seen between 45-50 percent of riders return — but the $3.9 billion in HEROES Act funding never arrived. The latest budget projections include a total deficit of $15 billion, as you can see below, and here is where this document turns political.

The MTA keeps asking for $12 billion in federal funding, and that number has raised eyebrows. Could the agency actually be this far into the red through only eight months of the pandemic? As the chart details, the answer is no, the MTA’s deficit does not stand at $12 billion for one year. Rather, this is the MTA’s ask across multiple years. To be whole through the end of this year, the MTA needs $2.4 billion – which it can secure through the Fed’s Municipal Liquidity Facility. That loan though will come with more interest that we the riders will have to pay off over the years. It’s an imperfect, though necessary, way to keep the trains running.

For 2021, the MTA’s immediate need is around $6 billion or half of its continued request. The agency then anticipates deficits of $3.6 billion in 2022, nearly $1.8 billion in 2023 and almost $2 billion in 2024 for a total of around $13 billion. Securing $12 billion in one lump sum gives the MTA flexibility to restructure this out-year deficits, incorporating whatever internal cuts the MTA can institute with the federal funding to show balanced budgets on paper, but its immediate needs are $6 billion. If that amount comes in, the MTA can fight anew for a few more billions for 2022 and 2023 – if the Biden Administration and whoever controls the Senate are still in the mood to pass stimulus packages.

Ask for all you need now because you don’t know what will come later. At its very heart, it is a political request, and the MTA is not shying away from politics. Earlier this year, MTA CFO Bob Foran stated the MTA’s ask included $1 billion to account for the Trump Administration’s slow-walking of congestion pricing, and the MTA is asking for more than it needs in the hopes that it can start negotiations with recalcitrant Senate Republicans at a higher baseline. It’s a dangerous game. For most of its existence, the MTA has been politically neutral while leaving the lobbying to politicians, but with federal politicians playing a game of economic chicken with states and municipalities, current MTA leaders have, at the behest of Gov. Cuomo, turned into partisan lobbyists. In fact, Foye recently penned letters to leading Georgia-based companies warning them that MTA capital funding could dry up without federal aid. This was a clear partisan shot aimed at drawing support for the Democratic candidates in the upcoming Georgia Senate run-off.

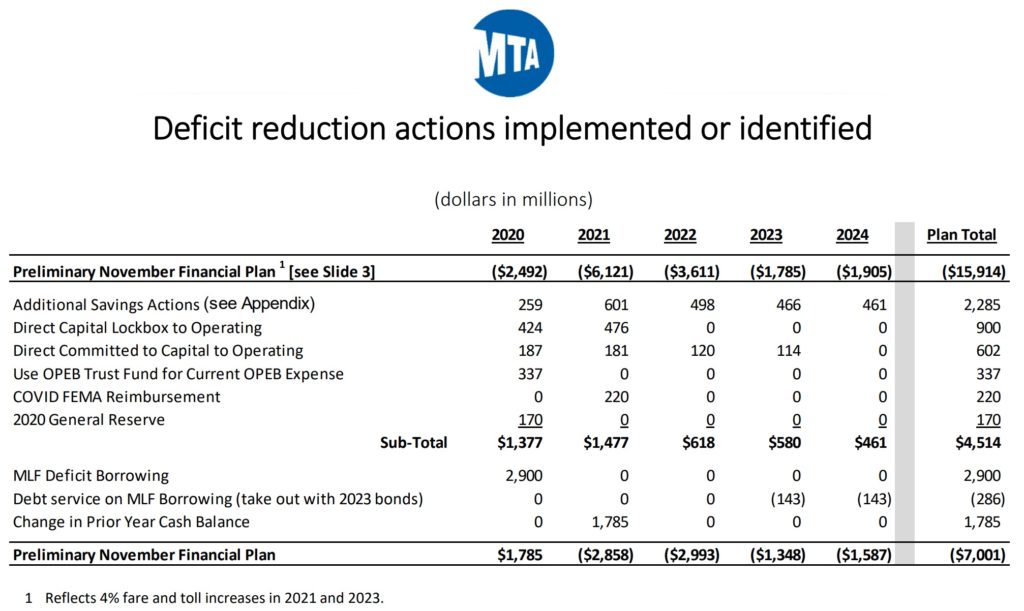

But the MTA is also hedging on its ask, aiming to draw out that $6 billion. Take a look at the MTA’s internal deficit reduction plan – a series of cuts that lowers its long-term deficit to a still-unmanageable $7 billion over five years.

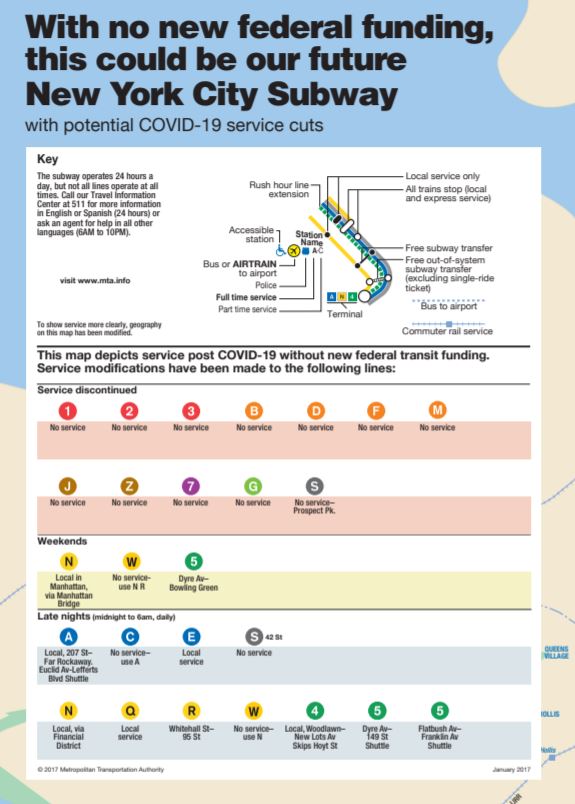

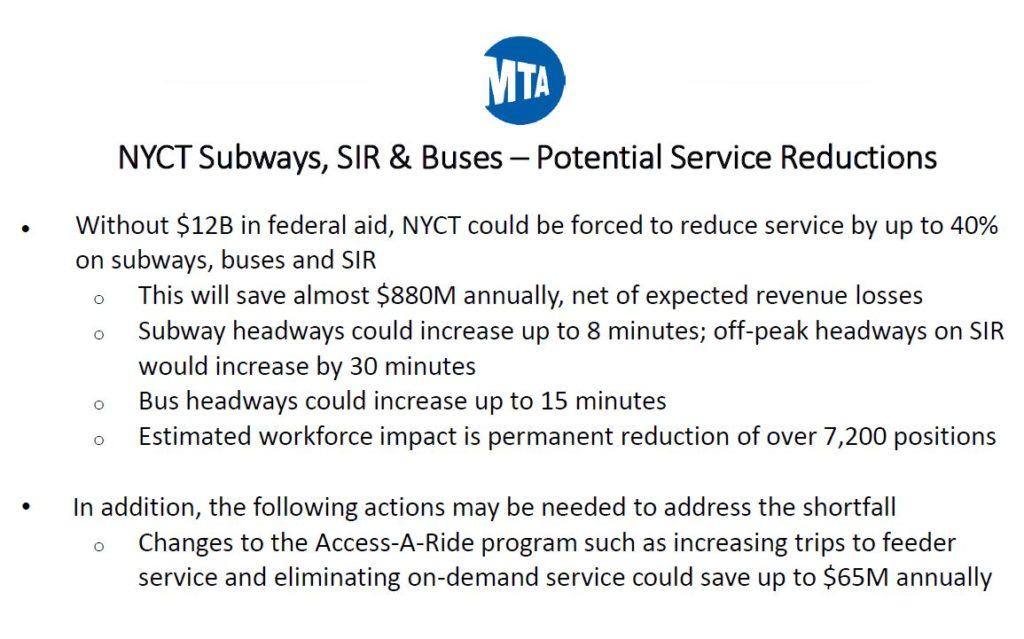

Make no mistake about it, though, these cuts would be devastating. The MTA plans to cut $343 million from annual subway service expenditures and $641 million from annual bus service expenditures. For subways, this means service cuts of up to 40%, including 15-minute weekend headways and other off-peak frequency adjustments. One of the questions driving a cut of this nature is whether the MTA can actually implement a 40% reduction in service. As with overnight trains running but without passengers, there is simply not enough room to park trains that aren’t running, and it’s not cost-efficient to cut service significantly. Just the thread is enough to see how this would ruin the subway system and save a small percent of what the MTA actually needs.

The buses, as always, would bare double the cuts as subways, and a 40% reduction of bus service would practically zero out many local routes. “Bus service reductions of up to 40% may result in reduced frequencies by up to

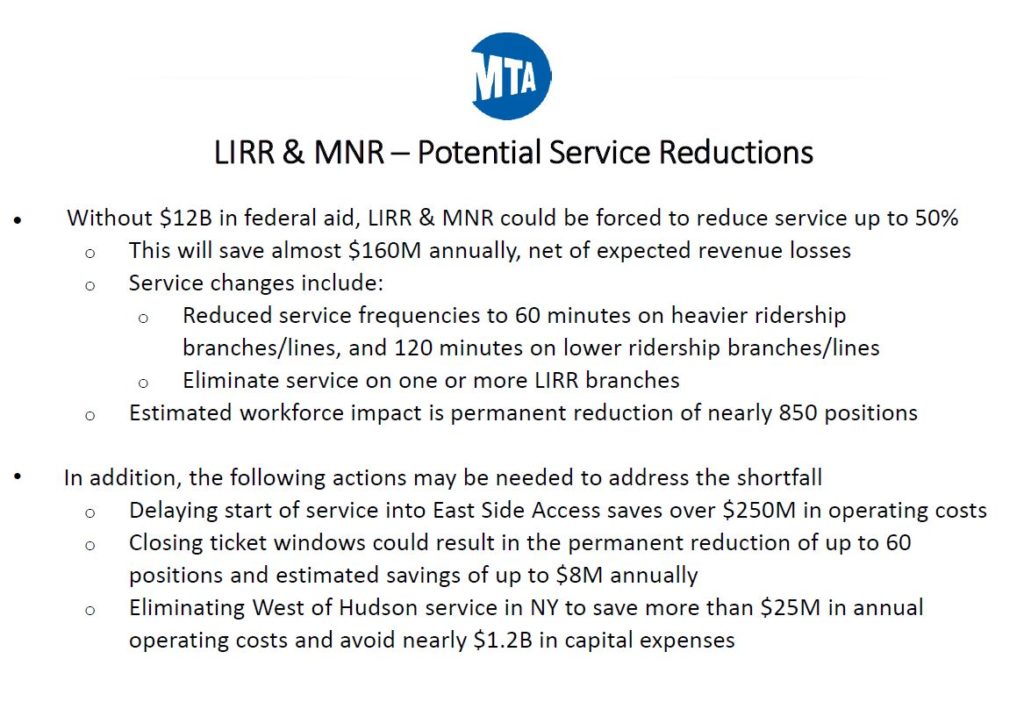

33% on bus routes that are not eliminated,” the MTA notes ominously. The agency is planning only $265 million in annual cuts to the LIRR and Metro-North but still halving service by up to 50 percent.

But this is all still a threat aimed at scaring the Senate into saving the MTA and the U.S. economy. In my view and in the views of many advocates, the MTA should cut service as a last resort, especially as the pandemic drags on and essential workers need to be able to maintain their commutes. “Failing to save transit at this pivotal moment is not an option,” Betsy Plum, executive director of the Riders Alliance, said. “Should Congress fail to act, the MTA’s doomsday budget must be the absolute last resort. As Chairman Foye said, literally everything must be on the table. At the end of the day, Governor Cuomo must do all he possibly can to safeguard our transit system and New York’s future.”

Yet, the MTA is heading down this path as a way to exert political pressure on Washington. Let New York fail? We dare you.

The state, in fact, has yet to do much to shore up its own struggling revenue picture, and Andrew Cuomo has a responsibility to ensure transit survives. I know various budgets and services have seen the pandemic blow billion-dollar holes through their budgets, but the state should look at other possible revenue streams — gas tax increases, legalizing marijuana, taxing the rich — while at the same time avoiding service cuts and lobbying for federal aid. (Streetsblog’s Dave Colon had a deep dive on this topic worth reading.)

As a last ditch resort before cutting service, the MTA should also look to restructure its debt and secure more credit. The state could help enable this as well by legislatively permitting the MTA to explore bankruptcy, an option currently foreclosed to it due to state prohibitions. This would be additional bargaining chips, designed to bolster political support in Washington for a direct transfer of funds back to a state that, in normal times, pays more in federal taxes than it gets back.

While we can appreciate the budget as the political document that it is intended to be and hope these service cuts are a threat rather than an omen, at some point, though, reality has to settle in. Mitch McConnell isn’t very likely to fund transit on his own, and the state should use the levers it has to cut into the MTA’s deficit so that subway and bus service could survive un-cut in a New York City on the rebound. Otherwise, with transit on the chopping block, cars will choke a city that grinds to a halt, hinder mobility and New York’s recovery and the national one at a time when the country can least afford it.