The MTA has taken a $10 billion hit due to the ongoing pandemic.

Ten years ago, during the depths of the Great Recession, the MTA faced a budget deficit we then considered massive. At the time, the agency was staring down a hole of $900 million, and to close the gap, the MTA implemented a series of staffing reductions, contract renegotiations and service cuts. Amidst the current coronavirus crisis, as the MTA is facing a $10 billion deficit over the next 18 months, I’ve been thinking more and more about the 2010 service cuts, how costly they were for commuters and how little money they ultimately saved the MTA.

The history of the 2010 cuts is a tortured one, and I’ll spare you the back-and-forth. In broad strokes, the MTA passed a budget at the end of 2009 that required the agency to implement cuts in 2010, and the cuts ran deep. As I detailed at the time, Transit eliminated two subway lines — the V and W trains — rerouted the M, pared back the G, and instituted new load guidelines so that trains wouldn’t be considered crowded enough to warrant more service until even more riders were crammed aboard. The cuts to the city’s bus network were even worse with over 40 routes partially or fully eliminated outright and service on others reduced to bare bones. Bus ridership, which was around 2.3 million per weekday prior to these cuts, has been in a downward spiral since then, bottoming out at 1.77 million per weekday last year.

For all of the inconvenience, added crowded, slower travel and worsened bus service, the MTA saved barely any money. The subway service cuts generated $16.6 million in annual savings and the bus reductions $51.2 million. The service cuts also lead to less revenue as the most inconvenienced riders will find other way to travel. Ultimately, then, cutting — at least on the service side — yields pennies while sacrificing frequency and travel times, key drivers of the utility of transit.

A $10 billion budget hole

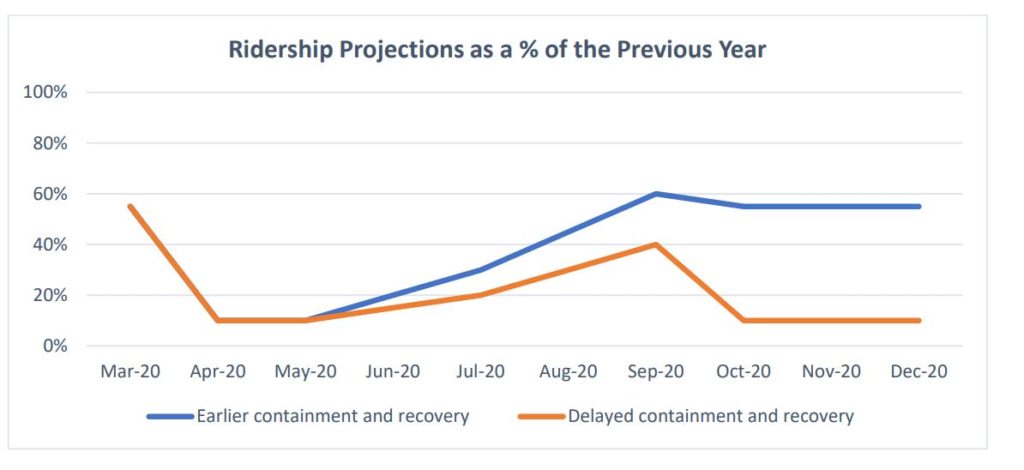

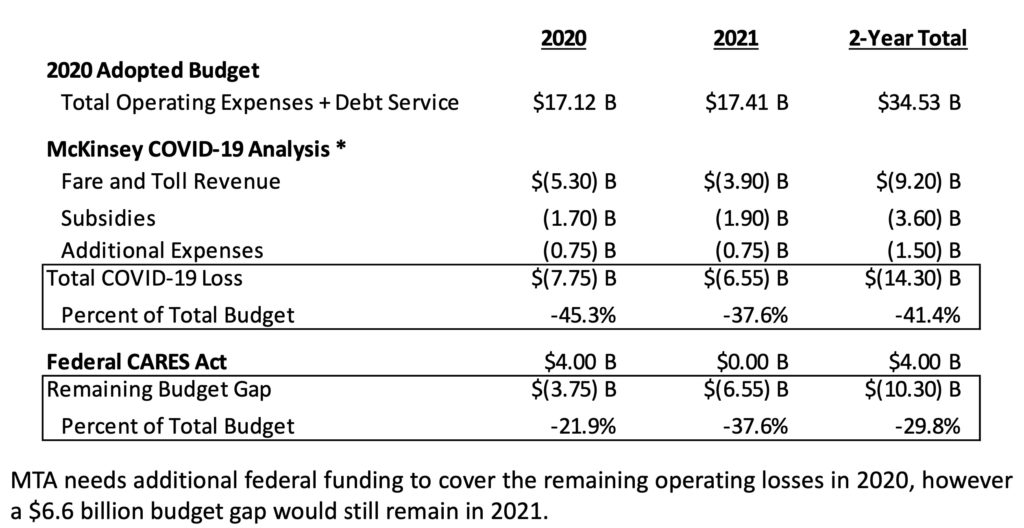

The MTA’s current crisis makes 2010’s budget deficit look like a walk in the park. Since March, the MTA has lost most of its riders, most of its toll-payers, much of its advertising revenue and a lot of the transit-supporting tax revenue. As the agency officials detailed in a presentation to Board members last month, the MTA faces a $3.75 billion deficit this year even after a $4 billion infusion of CARES Act cash and approximately $6.6 billion next year. Senior leadership has engaged in a media blitz, lobbying constantly for federal funding (though most of the TV appearances have been local to New York where the Congressional delegation already supports a federal transit bailout rather than national). At this point, though, one “Fox & Friends” appearance by Pat Foye would be more likely to move the right needle than ten more NY1 hits.

This week, the MTA Chair took his message to The Wall Street Journal, as Paul Berger, the paper’s transit beat writer, took a deep dive into the financial state of the MTA:

The nation’s largest transit system teeters on the edge of an unprecedented financial crisis as it emerges from the new coronavirus pandemic, leaving it with few options other than imposing major spending cuts and borrowing billions of dollars, officials say. Patrick Foye, chairman of New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority, said in a July 8 interview that the only way to stave off bleak measures is for the agency to secure $3.9 billion in federal coronavirus bailout funds in the coming weeks. Without the money, subway, bus and rail commuters could be consigned to diminishing services for years. “None of the choices are good, which is why the federal funding is essential,” he said.

The state-controlled authority, which runs New York City’s subway and bus systems as well as two commuter railroads, has almost exhausted $4 billion it received as part of the first federal coronavirus bailout in May. The Democratic-controlled U.S. House of Representatives included a further $3.9 billion for the MTA in a new $3.5 trillion relief package passed the same month. Mr. Foye said he remains cautiously optimistic about receiving the money soon, even though the bill has languished in the Republican-controlled U.S. Senate.

Senate Republicans, who return from recess July 20, have rejected the bill and remain divided on how much to spend and what to spend it on. Standard & Poor’s on Tuesday downgraded the MTA’s credit rating to BBB+ from A-. It said the first round of bailout funds will be exhausted by August and described the authority’s hopes of receiving a next round of federal funding as fading. Even if the authority receives the money, it would last only through the end of this year.

So what comes next?

The MTA cannot cut its way out of this hole…

A Riders Alliance study paints a bleak picture of the MTA’s doomsday scenario.

If the Senate fails to act in the coming weeks, the future is bleak for the MTA and for transit in New York City. The Riders Alliance determined that without federal funding, the MTA would have to generate cuts 20 times more impactful than the 2010 service reductions, and the advocacy group painted a picture of a Doomsday scenario in which half of all subway service is eliminated. Needless to say, New York City as we know cannot exist or rebound with half of its normal subway service, and the report is written to help riders conceptualize the depths of the MTA’s budget crisis. It’s not in any way, shape or form predictive of the future. Yet.

In the past, as Betsy Plum, executive director of the Riders Alliance, told The Journal, the MTA’s financial woes have worked themselves out, but this time, the deficit is simply too large for it to work itself out. “We may truly be in a moment where it cannot work itself out without dramatic injury to the people who most rely on transit,” Plum said to Berger.

Dramatic injury isn’t an outcome anyone wants. MTA leaders hope to avoid pandemic-related service cuts, and fare hikes — other than those already scheduled for 2021 — are off the table. After all, as with service cuts, a 500% fare hike would make the system unaffordable for millions of people who rode pre-pandemic and would exacerbate the city’s financial and affordability crisis. The hole is simply too deep for the MTA to use its usual set of tools to balance its budget, and we should view the MTA as a public good, required during a pandemic and vital to the city’s success all other times. It should always be funded that way.

…Which is not to say they shouldn’t try

Yet, as we well know, the MTA is not a paragon of efficiency, and the current crisis should cause the agency to do some soul-searching on its runaway cost problems. After all, if the MTA cannot reform its spending practices now, amidst the worst budget crisis in 50, if not 91, years, when can they expect to do so?

Most commentators do not seem to grasp the depths of the dollars ands have urged modest business-as-usual approaches. The Citizens Budget Commission issued a new report this week, and while they acknowledged the depths pf the crisis, their five recommendations sounded like every other CBC recommendations on transit spending we’ve heard over the last few decades. “Achieve greater efficiencies”? “Prioritize planned capital projects”? “Optimize service levels”? Borrow money? Those seem like fine suggestions for closing a $100 million budget gap but seem woefully inadequate for some 10 times that size, let alone 100 times, as the MTA currently faces.

Other ideas have more legs. While the MTA may not be able to cut $6 billion and still operate any trains or buses, the savings are there for the taking as The LIRR Today discussed last month:

There’s not $10 billion worth of things to cut, but there’s plenty of room for cost savings, and you don’t even have to look all that hard. Instituting proof of payment on the railroads and eliminating conductors will on its own save about $411 million per year. If LIRR and Metro-North were both forced to cut down their vehicle maintenance costs to the nationwide average without impacting reliability, that would save $347 million per year. Just making LIRR operate as efficiently as Metro-North (not a high standard, by any means) would save $121 million per year. Going to One Person Train Operation (OTPO) on all subway lines, a practice ubiquitous elsewhere in the world, would save about $300 million yearly. There are certainly no shortage of ways to further reign in overtime spending. And that’s just scratching the surface…

Internally, the MTA has options too. Sarah Feinberg, the interim president of NYC Transit, wants to cut spending on pricey consultants as she reorganizes the massive workforce powering subways and buses, and the MTA has outlined what it could do if the federal funding doesn’t come through. To that end, the MTA could use congestion pricing revenue (if the program is approved by the feds) to bond out operating expenses; reduce the workforce; freeze wages; borrow more; or, as a last-gasp measure, cut service and raise fares. It shouldn’t come to that end though as the city can least afford it.

In the end, the MTA will not and cannot go bankrupt. The state will backstop the debt if push ever comes to shove. But as capital and cash dry up, the feds should come to transit’s, and to cities’, rescue, and the MTA should try to explore real and substantive cost control while pushing hard for that bailout. New Yorkers can’t afford an NYC without transit and neither can the country, whether the Senate wants to admit it or not.